Key Points

- Bangladesh effectively collaborated with local and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in designing interventions and the country’s CHW model.

- Through successful coordination with donors and partners, Bangladesh developed a Sector-wide Approach (SwAP) that shifted the country’s U5M strategy from disease-specific, project-based “vertical” funding and programming to a “horizontal” approach.

- Bangladesh used data to inform decision-making, through partnering with local research institutions, leveraging disease-specific surveillance systems, and integrating interventions into health management intervention systems (HMIS).

- Financial, gender, and geographic equity were accounted for in the rollout of interventions.

Several of Bangladesh’s implementation strategies are adaptable to other countries looking to reduce under-five mortality (U5M) rates. More detail on these strategies can be found in the sections that follow.

Working Closely with Partners in the Management of CHWs

One of the most distinctive features of Bangladesh’s U5M efforts is the prominence of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), both homegrown and international, in a broad range of capacities.

Other countries may have comparably large NGO sectors, but Bangladesh is remarkable in that several highly effective large-scale domestic organizations operate within the country. For example, BRAC (originally the Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee, now known only by its initials) is one of the largest NGOs in the world, and Grameen Bank is a microfinance organization that won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for its work providing basic financial services to the poor.

Evidence of close coordination between the government and NGO sectors was apparent throughout the study period, and across almost all categories of U5M interventions. NGO partners provided a wide range of support to government efforts to reduce U5M, from pilot testing to implementation to the collection of data.

Nongovernmental entities that played a significant role in U5M interventions included professional organizations, such as the Obstetrical and Gynaecological Society of Bangladesh, the Bangladesh Neonatal Forum, and the Bangladesh Pediatrics Association.

These professional bodies were often central participants in decisions related to the design and implementation of specific interventions, for example, when facility-based IMCI and the community-based skilled birth attendant program were adapted for the Bangladesh context.

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW) National Newborn Technical Working Group, which provided coordination for all neonatal programming activities in Bangladesh, included members from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the Bangladesh Neonatal Forum, and the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research (ICDDR,B).

[For more information on these and other specific interventions, see the What Did Bangladesh Do? Article in this narrative.]

An especially vivid example of government-NGO collaboration to reduce U5M was the development and deployment of Bangladesh’s community health workers (CHWs). Distinctive among U5M exemplar countries, both the government and the NGO sector had a hand in developing Bangladesh’s CHW model.

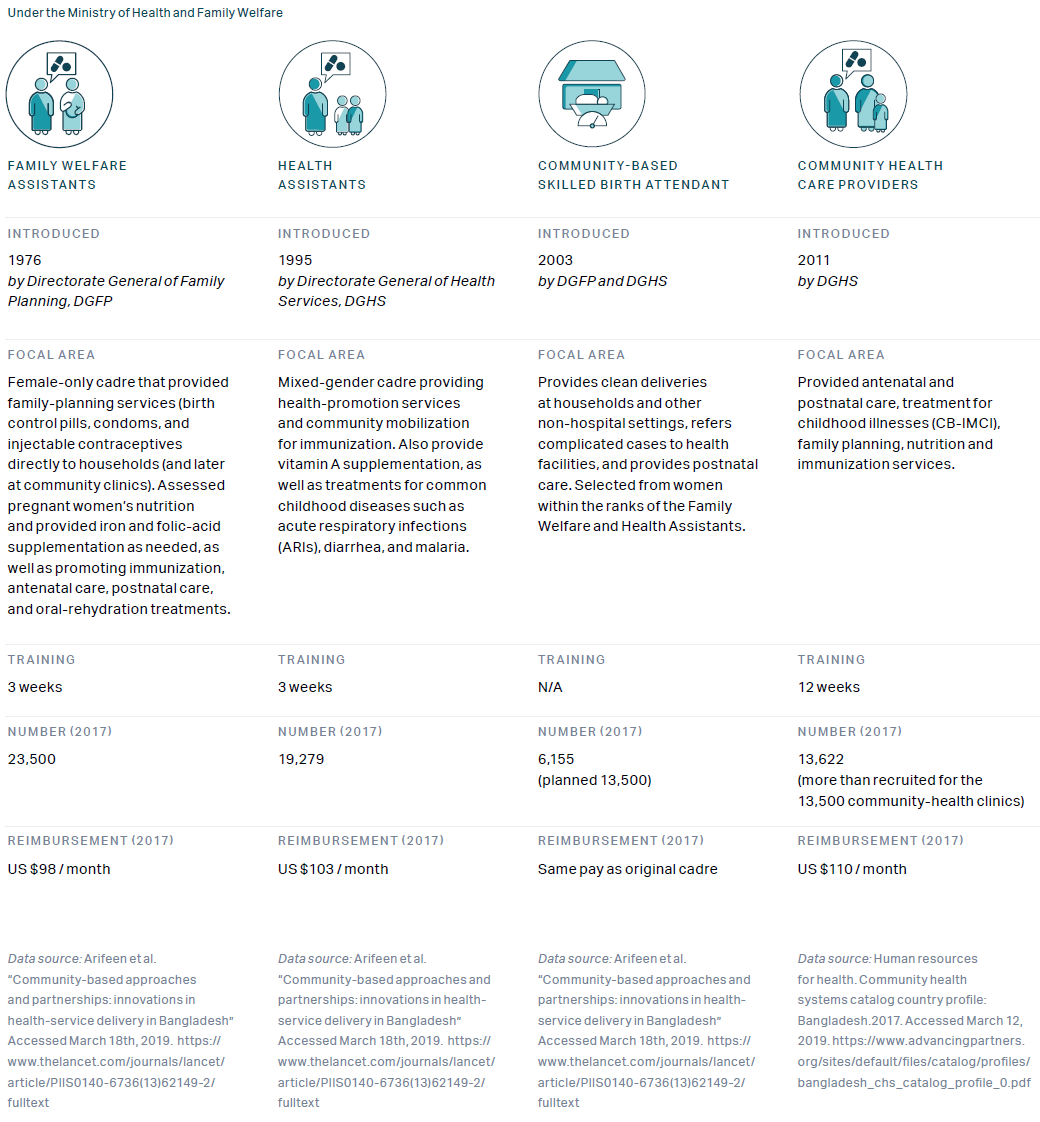

Initially, the country had two main groups of CHWs, each under a separate directorate of the MOHFW.1,2 The first of these were the family welfare assistants, under the Directorate General of Family Planning (DGFP) within the MOHFW. Family welfare assistants were introduced in 1976 as a female-only cadre of CHWs that provided family planning services, assessed pregnant women’s nutrition, and promoted immunization, antenatal care, postnatal care, and oral rehydration treatment (ORT).3

The second group of government-sponsored CHWs were health assistants, introduced in 1995 as a mixed-gender cadre employed by the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) to provide health promotion services and community mobilization for immunization.3

As an important additional resource, in 1998 the government established a national network of community clinics. This decision was squarely in accordance with an emerging global consensus4 that building effective community-level facilities can powerfully complement the work of CHWs.

The community clinics were staffed by CHWs and provided a crucial link to basic medical services in rural communities and small towns. A change in national administrations resulted in a shutdown of the clinics in 2002 until they reopened in 2009.

[For more information on community clinics, see the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness section in What Did Bangladesh Do?.]

Since 2009, the DGFP and DGHS have both introduced additional CHW cohorts. In 2003, the DGFP introduced the Community-Based Skilled Birth Attendant cadre, which provides clean deliveries at households and other non-hospital settings; refers complicated cases to health facilities; and provides postnatal care. In 2011, the DGHS introduced a cadre of community health care providers to meet the increased demand for primary care services2 following the reopening of community clinics. The community health care providers provided antenatal and postnatal care, treatment for childhood illnesses, family planning, nutrition and immunization services.

Government CHW Cadres

Government program overview

[For more information on difficulties with CHW staffing, retention, and coverage, see the Challenges chapter in this narrative.]

Even with the expansions of the government’s CHW cadres, the majority of CHWs in Bangladesh were nongovernmental. For example, when the government introduced community-based Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (CB-IMCI), it enlisted NGOs with deep experience in selected districts, such as Save the Children and BRAC, to implement the program in those areas. BRAC CHWs were by far the largest group of NGO health workers and were organized into two primary groups.

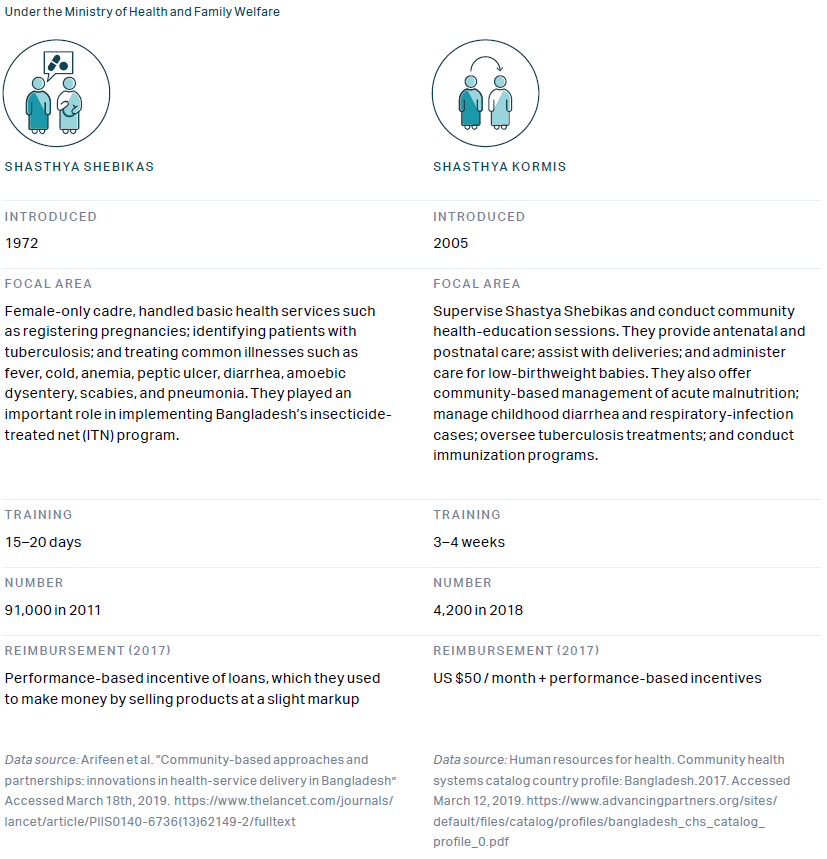

The first of these groups was the Shasthya Shebikas. This female-only cadre, introduced in 1972, handled basic health services such as registering pregnancies, identifying clients with tuberculosis, and treating common illnesses. They played an important role in implementing Bangladesh’s insecticide-treated net (ITN) program (see What Did Bangladesh Do? chapter).

In 2005, BRAC introduced the Shasthya Kormis, a new group of CHWs responsible for supervising the Shasthya Shebikas and conducting community health education sessions. They provide antenatal and postnatal care, assist with deliveries, and administer care for low birth weight babies.

Non-governmental CHW Cadres

BRAC program overview

[For more information on the community health worker programs, see the Exemplar narrative on CHWs in Bangladesh (Exemplars in Global Health: Community Health Workers in Bangladesh).]

Making Effective Use of Partner Resources – Both Financial and Technical

Bangladesh’s openness to NGO and partner involvement has not been limited to groups from within its own borders. International donor funding and support from implementing partners were key contributors to the country’s success in U5M reduction, with multilateral organizations such as the World Bank, Gavi, and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria investing significantly in a wide range of initiatives throughout the 2000–2015 study period.

The involvement of such global organizations was by no means solely financial; they also provided valuable expertise and participated in various MOHFW technical working groups.

An important mechanism for the government’s engagement with donors and partners was the Sector-Wide Approach (SWAp), which was introduced in 1998 and continued in sequential five-year phases throughout the study period. This initiative shifted Bangladesh’s U5M strategy from disease-specific, project-based “vertical” funding and programming to a “horizontal” approach supporting the health sector as an integrated whole.

SWAp required donors to channel their funding into the broader health sector rather than directing it to their own favored programs. Yet SWAp also represented a further deepening of the relationship between the Bangladeshi government and NGOs, since it called for the development of detailed operational budgets and plans for each program – a process that included donors and partners as central participants.

Data-Driven Implementation

An emphasis on the collection and usage of empirical evidence was a consistent feature of Bangladesh’s U5M efforts. The country had a history of data collection through its Health Management Information System (HMIS) and various surveys over time, including the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, the Service Provision Assessments, and health facility surveys starting in 2014, in addition to ongoing Demographic and Health Surveys.5

Bangladesh’s evidence-based interventions usually began with a strengthening of data systems to ensure accurate monitoring and evaluation. This could be seen in the integration of facility-based Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (FB-IMCI) and several other evidence-based interventions into HMIS, and in the use of DHS data to track incidence and care-seeking rates for illnesses covered by FB-IMCI.

The country drew upon its extensive CHW network to improve data collection. During house calls, government CHWs compile a household inventory of health conditions and basic demographic information. The data is then shared with supervisors and used for planning purposes. This feedback loop enables programs to adapt to changing needs and ensures that local cultural and financial realities are considered as part of the program design. BRAC also incorporates data collection into its CHWs’ regular household visitations.

Bangladesh also had disease-specific surveillance systems, which it leveraged throughout the study period. For example, the MOHFW used its pediatric bacterial meningitis and pneumococcal disease sentinel surveillance system to monitor the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV). Similarly, Bangladesh’s measles surveillance drew upon the existing polio-detection system.

In addition to using data to monitor and evaluate evidence-based interventions, the government and its NGO partners used it for decision making at several junctures.

Examples of how data informed decision making include the country’s early decision to focus on neonatal care, the setting of vaccination schedules, malaria treatment, and the rollout of antimalaria campaigns.

Despite a history of drawing upon quantitative evidence to inform decision making related to interventions, the use of data in Bangladesh has been far from trouble-free.

One ongoing challenge has been low levels of data availability. In 2014, Bangladesh introduced an electronic Health Information System (e-HIS) and set up an HMIS unit within the DGHS. Yet even after these policies went into effect, in a 2016 study of electronic maternal, newborn and child health information systems, Bangladesh scored 1 out of 15 possible points for availability of key data elements related to lifesaving interventions and health outcomes (compared with an average of 8.65), the lowest score of all 22 countries assessed.6

Whatever challenges Bangladesh may have encountered in the use of data, its U5M interventions demonstrate a keen appreciation of the value of local research and testing in the assessment and adaptation of current programs.

Partnership With Local Research Institutions

The presence of strong data systems like HMIS and surveys such as DHS helped support data-driven decision making, as did the close partnership between government and local research organizations such as ICDDR,B, whose Matlab location – the longest-running demographic surveillance site in the Global South – heavily informed and influenced government and NGO policies and programs.

As noted in the Context article of this narrative, the research leadership provided by ICDDR,B and other in-country organizations was vital to the advancement of data-centered strategies to reduce U5M.

Bangladesh’s use of this local research capacity is unique among Exemplar countries, and it influenced policy on numerous interventions, including FB-IMCI.

For example, neonatal mortality data convinced the government to set the lower age limit for FB-IMCI to 24 hours as opposed to the seven days recommended by WHO and UNICEF. Localized studies conducted by ICDDR,B and Bangladesh’s Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research provided the basis for Bangladesh’s decision to introduce rotavirus vaccine.7

To inform its decisions on whether and how to expand interventions, Bangladesh often conducted small-scale tests of feasibility and effectiveness in partnership with local research organizations.

For example, findings from the small-scale testing phase informed the phased expansion of FB-IMCI and CB-IMCI starting from the subdistricts with the highest U5M rates and expanding to those with lower rates.

The unusual addition of a non-medical condition – drowning – to CB-IMCI was based on local evidence finding that it was a significant cause of death among children in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh adapted new evidence-based interventions to suit specific community contexts by drawing upon local evidence. In addition to improving the effectiveness of interventions, this practice engaged and strengthened in-country research institutions, which in turn fostered an even deeper culture of data-driven decision making.

-

1

El Arifeen S, Christou A, Reichenbach L, et al. Community-based approaches and partnerships: innovations in health-service delivery in Bangladesh. Lancet. 2013;382(9909):2012-26. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62149-2. Accessed March 18, 2019.

-

2

Farnham Egan K, Devlin K, Pandit-Rajani T. Community Health Systems Catalog Country Profile: Bangladesh. Arlington, VA: Advancing Partners and Communities; 2017. https://www.advancingpartners.org/resources/chsc/countries/bangladesh. Accessed March 12, 2019.

-

3

Exemplars in Global Health. Exemplars in Global Health: Community Health Workers in Bangladesh. Seattle, WA: Exemplars in Global Health; 2019.

-

4

Heymann DL, Chen L, Takemi K, et al. Global health security: the wider lessons from the west African Ebola virus disease epidemic. Lancet. 2015;385(9980):1884-1901. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60858-3. Accessed December 12, 2019.

-

5

Eminence Associates for Social Development. Writing About Health: A Handbook for Journalists (Bangladesh). Dhaka, Bangladesh and Calverton, MD: Eminence and ICF Macro; 2013. https://www.thecompassforsbc.org/project-examples/writing-about-health-handbook-journalists. Accessed August 31, 2018.

-

6

Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP). Health Management Information Systems (HMIS) Review: Survey on Data Availability in Electronic Systems for Maternal and Newborn Health Indicators in 24 USAID Priority Countries. Washington, DC: MCSP; 2016. https://www.mcsprogram.org/resource/health-management-information-systems-hmis-review/. Accessed December 12, 2019.

-

7

Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Application Form for Gavi NVS Support: Submitted by the Government of Bangladesh. 2016. https://www.gavi.org/country/bangladesh/documents/proposals/proposal-for-nvs---rota-support--bangladesh-2017/. Accessed December 12, 2019.

-

8

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Bangladesh. Community based health care. http://www.communityclinic.gov.bd/index.php?id=2. Accessed December 12, 2019.