Finding Exemplars Among Those Who Restored Vaccine Confidence: a Pathway for COVID-19 Recovery

These are troubling times. We are in the throes of a hyper-infectious, disabling, and sometimes fatal COVID-19 pandemic, which has sparked a cascade of knock-on effects. Beyond health, efforts to control the spread of the pandemic have caused wider societal disruption, lost schooling, economic disasters, and exacerbated all of the pre-COVID fault lines of inequities, marginalization, and growing distrust in government. In the background of all these individual and collective disruptions, is the persisting uncertainty of: What’s next?

One antidote to the ubiquitous uncertainty around COVID-19, and waning trust in government guidance around the pandemic response, is to rebuild confidence with the public by recognizing their needs beyond COVID-19. Targeted efforts to start to normalize life by slowly reintroducing known and familiar health and development interventions in a hyper-uncertain environment can be a crucial means to rebuild trust and support an eventual post-pandemic recovery.

As the 2020 Goalkeepers Report called out, “we’ve been set back 25 years in 25 weeks.” Catching up on the millions of missed childhood vaccinations, for instance, is one tangible way to start to rebuild public confidence, while using the opportunity to talk with parents about other concerns they may have, including access to a possible COVID-19 vaccine.

Ten years ago, I founded the Vaccine Confidence Project with the ambition of trying to put some metrics around the complicated issue of public sentiments and emotions surrounding vaccines. We knew that these emotions, individually and collectively, were starting to take a toll on vaccine uptake and disrupting immunization programs in some settings. But we did not have a sense of the scope or scale of these disruptions, nor their impacts. Nor did we have a measure of public confidence in vaccines which we could track over time to anticipate changes in confidence before these sentiments influenced vaccine uptake. Such a metric provides an opportunity to understand what is causing drops – or gains – in confidence and inform appropriate interventions to rebuild public trust.

In 2015, we launched the Vaccine Confidence IndexTM initially investigating levels of vaccine confidence and reasons for low confidence in five countries which had a history of managing a vaccine crisis: Georgia, India, Nigeria, Pakistan, and the United Kingdom (UK). Based on this in-depth five-country analysis, we narrowed down the core questions that had the most influence on vaccine acceptance – including whether vaccines are important, safe, effective, and compatible with religious beliefs – to create the VCITM.

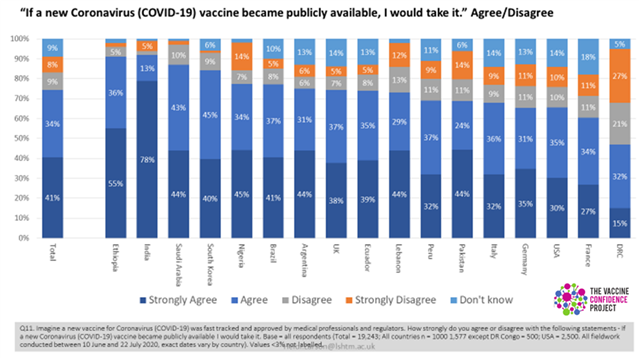

In the context of COVID-19, we incorporated COVID-related questions into our surveys and social media monitoring to explore the sentiment and emotions around governments’COVID-19 response more broadly and the public’s anticipated willingness to accept a COVID-19 vaccine.

This month, we published new research in The Lancet, “Global Trends in Vaccine Confidence,” mapping global trends in vaccine confidence across 149 countries between 2015 and 2019, based on VCI and other relevant data from over 284,000 adults (aged 18 years and older). We modelled the relationship between vaccine uptake in each country and demographics (i.e. age, sex, religious beliefs), socioeconomic factors (e.g. income, education), and source of trust (e.g. family, friends, health professionals).

The study showed that overall confidence in both the safety and effectiveness of vaccines was mixed – similar to the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance surveys (Fig 1). In the Lancet study, we found that vaccine confidence – including perceptions of safety, effectiveness, and importance – has fallen between 2015 and 2019 in Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, Serbia, and South Korea. It remains high in India and is growing in many European countries. Brazil showed a trend of slightly declining confidence. Together, these changes point to the need for trust-building to support not only routine vaccination but to also prepare for a potential COVID-19 vaccine across a wide number of countries.

Surveys conducted by others on the anticipated willingness to accept a COVID-19 vaccine, have been generally consistent with our confidence mapping around vaccines more broadly. This suggests that our research could be a useful tool for identifying and mapping areas that need to be targeted for confidence building interventions in advance of a COVID-19 vaccine.

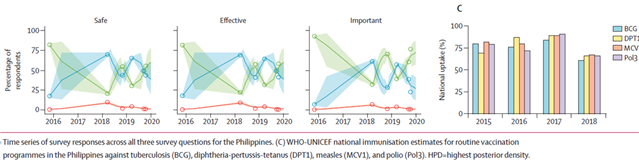

The Philippines provides some guidance on how this can be achieved. In 2018, a newly reported risk from a dengue vaccine (Dengvaxia), just over a year after its introduction, led to a dramatic drop in public confidence in vaccine safety and effectiveness and impacted the uptake of routine vaccines. The Philippines dropped from being in the top 10 countries with the highest overall vaccine confidence in 2015 (82% of those surveyed strongly agreeing that vaccines safe, 92% important, 81% effective), to ranking no higher than 70th in 2019 (58% those surveyed strongly agreeing that vaccines safe, 70% important, 57% effective). But, concerted efforts by the health authorities to rebuild trust through numerous outreach and engagement activities, including innovative on-line resources and opportunities for conversations – not just around the vaccine, but in the system more broadly – led to a rebuilding of confidence captured by the figures below. The Philippines example reflects a different kind of “exemplar” – an exemplar in recovering from a vaccine confidence crisis and building more resilience to potential future shocks. This renewed trust and confidence building will undoubtedly support the introduction and uptake of an eventual COVID-19 vaccine.

de Figueiredo A, et al. Lancet 2020

Indonesia was another country in our study that witnessed one of the largest falls in public trust worldwide between 2015 and 2019 (absolute difference in perception of safety fell 14% [from 64% to 50%], importance 15% [75% to 60%], effectiveness 12% [59% to 47%]). This was triggered by some Muslim religious leaders who questioned the safety of the measles and rubella (MR) vaccine and issued a fatwa (religious ruling) claiming that the vaccine was haram (forbidden) and contained ingredients derived from pigs, additionally local healers promoted natural alternatives to vaccines. In an effort to build confidence in the vaccine, the government and partners produced videos featuring Muslim leaders persuading parents to vaccinate their children, along with other targeted and nuanced communication efforts, including dialogue between political, health, and religious leaders.

Slides in vaccine confidence reflect changing relationships between the public and government, civil society, and religious authorities and point to the need for confidence building in immunization programs and health systems more broadly. The current COVID context is an opportunity to build trust by addressing public concerns, including and beyond vaccination.

It is vital with new and emerging disease threats such as the COVID-19 pandemic, that we regularly monitor public confidence in health and development interventions to help guide where we need to build trust to optimise uptake of not only life-saving vaccines, but health and development efforts more broadly. Trust will be fundamental if we are to regain the 25 years of progress lost in 25 weeks.

Dr. Heidi J Larson, PhD

Director, The Vaccine Confidence Project

Professor, Dept of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

Clinical Professor, Dept. Health Metrics Science, University of Washington, Seattle

@ProfHeidiLarson