'My biggest fear is we will forget'

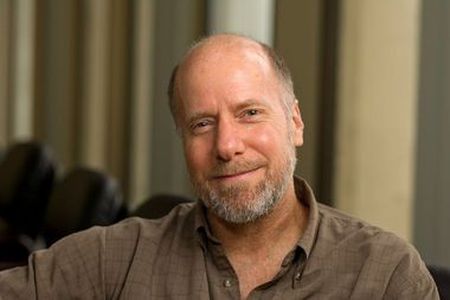

Dr. Daniel Bausch, Director of Emerging Threats & Global Health Security at FIND, discusses the COVID-19 vaccine rollout, nationalism and equity – and the need to preserve our pandemic memory

Dr. Daniel Bausch's biggest fear about the COVID-19 pandemic isn't necessarily the emergence of new variants or the vaccine nationalism that reared its ugly head as countries scrambled to inoculate their citizens at the expense of their neighbors. His biggest fear is that the world will go back to "too much normal" too quickly and forget the pandemic's painful lessons, especially in public health preparedness.

In an interview, the president-elect of the American Society of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene, said that forgetting is the biggest danger. "We’re quite fickle with [pandemics] and when things stabilize and we go back to something approximating normal, then people will say ‘why should we put money into preparedness in public health when there’s nothing going on right now?’” he said.

Dr. Bausch, who is also a professor at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, also called vaccine equity one of the "major challenges" in the global quest to inoculate the world's population from COVID-19 and outpace the rising variants of concern or interest that may escape immunity.

Equity, or more accurately, lack of equity, has been a running thread of the pandemic. Worldwide, COVID-19 has disproportionately killed more people of color, it has more disproportionately affected those of low socioeconomic status, and it has more disproportionately affected those in rural – versus urban – areas. The reasons are not unexpected: lack of access to adequate health care and pre-existing comorbidities are among the top predictors of COVID-19 mortality.

“The pandemic has revealed that the systems are fragile,” Dr. Bausch added in a video call from his office in Geneva. And when fragile systems are stressed, they can be pushed to the brink.

That stress can be observed in a new, troublesome data point. According to Our World in Data, on June 15, 2021, only 20.7 percent of the world’s population had received at least one shot of a vaccine. In low-income countries, less than one percent had.

Dr. Bausch blames vaccine nationalism, which occurs when some countries purchase massive quantities of vaccine, preventing many others from accessing it. “Vaccine nationalism has reared its head,” he said. Vaccine nationalism is predicated on those familiar safety instructions flight attendants give before take-off: in case of an emergency, put a mask on yourself first, before helping others. But for a disease like COVID-19, that can cause a significant delay in the global recovery.

Although vaccine nationalism may be one of the biggest reasons for vaccine inequity, Dr. Bausch tried to remain non-judgmental. “The first thing one does is to protect your own,” he said.

Lack of equity and vaccine nationalism have not been the only challenges, said Dr. Bausch, who specializes in the research and control of emerging tropical viruses.

Resource-rich countries in the global north have been, for the most part, the largest producers of vaccines. It’s a model that can complicate things downstream, and even more so when the demand is generated by a global pandemic. COVAX was created to solve for this, by pooling resources from rich countries so LMICs that can’t produce their own vaccines would have fair and equitable access but, as Dr. Bausch said, “it has not really worked.” It’s an opinion shared by others.

The UN, which is one of COVAX’s backers, has expressed concerns over vaccine nationalism, supply-chain challenges stemming from export bans or price controls, and a global shortage of manufacturing capacity.

For the next pandemic, Dr. Bausch says we should look for alternatives. “There are only a few places in all of sub-Saharan Africa that produce any vaccine,” he said, and many are fill-and-finish facilities that essentially bottle doses. This can be fixed, he argued, but not by having every country build capacity to make their own vaccine. “That’s not possible or even desirable. But we could think of a regional approach, right?” he said. “You could envision a West African producer, and a North African producer… so that when the next emergency happens, you don’t have countries sort of begging from countries on the outside” for their shots.

And that is precisely what has happened with COVAX. “It’s became almost a donation drive,” from rich countries being asked to give excess doses they had ordered even before clinical trials were concluded. Many of those doses had been purchased from India’s Serum Institute, the world’s largest COVID-19 vaccine producer.

But in April 2021, when a more transmissible and more dangerous B.1.617 Delta variant caused a deadly second wave in India, the country suspended all vaccine exports, so it could use serum’s supply at home. “I would defy almost any nation on Earth to do differently in the same situation. Or really, any family. Protecting the ones you love is human nature,” Dr. Bausch said.

It’s a fragile landscape. Most LMICs cannot produce or afford their own vaccines, so they depend on others. Others tend to take care of one’s own before surrendering doses. For a virus that is so easily transmitted across borders and given the havoc COVID-19 has caused for all, a global post-mortem will be essential. “It’s already happening” Dr. Bausch stated, explaining that he already sits on various committees and boards. And even if he jokes that there will be “more post-mortems than we can count,” or that their findings won’t be consistent “in part because they never are, and in part because this is complex,” he does believe there are lessons we have already learned.

“The thing that stops any outbreak is the local response. It’s getting people on the ground, in a community to say ‘I recognize this is a problem and I’ll change my behavior. I’ll wear a mask, get a vaccine, or do what it takes,' and that’s what really counts," he said.