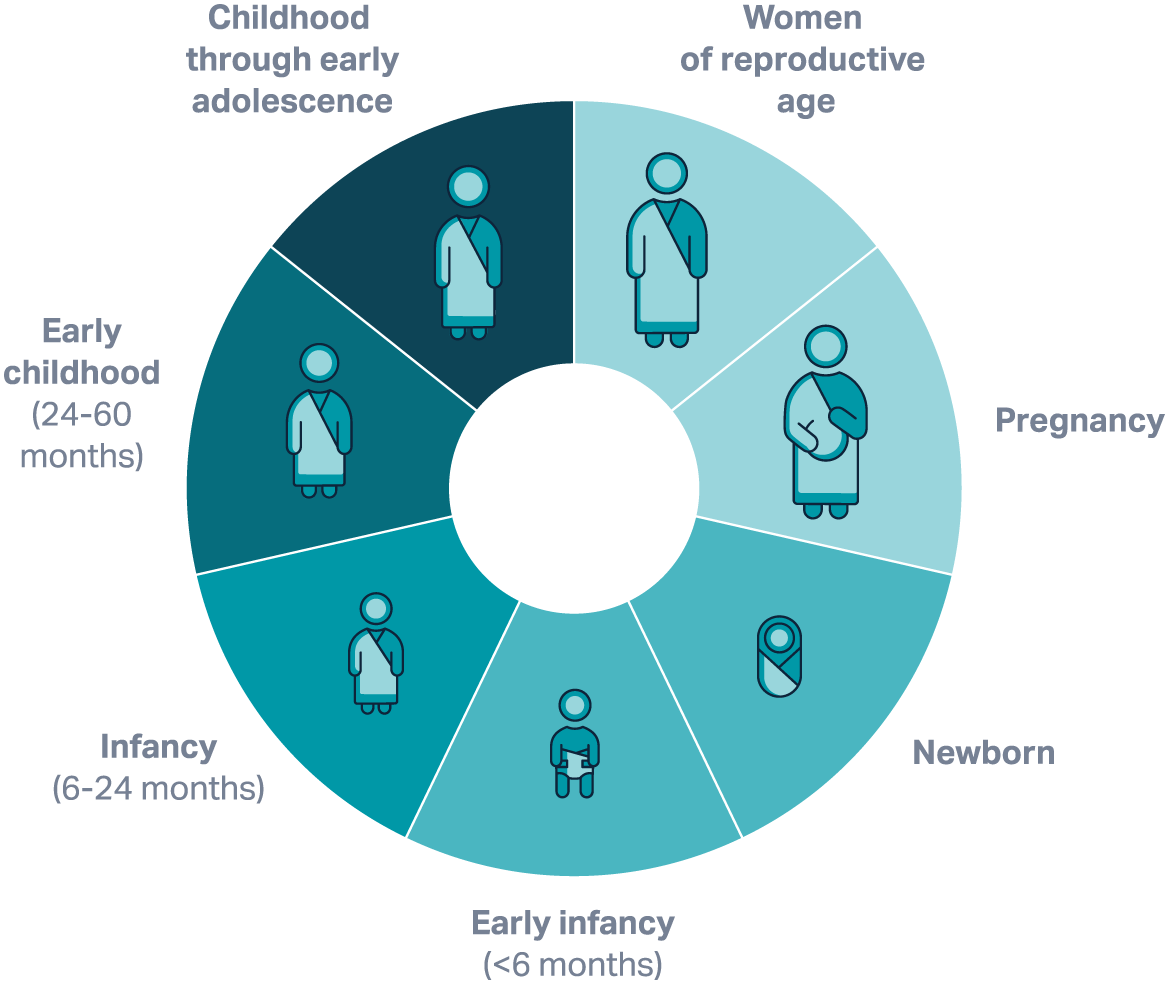

Maternal and Infant Nutrition and Growth

Globally, more than a billion women are malnourished and a quarter of children under five are experiencing stunting and/or wasting., Improving maternal nutrition can help disrupt an intergenerational cycle malnourishment by promoting healthy fetal development and reducing risk of growth faltering from the start. This, in turn, can reduce the risk of undernourishment amongst girls, who are often likely to become undernourished mothers who then give birth to small and vulnerable newborns.

Quick facts on maternal and infant nutrition and growth

Stunting is the failure of children to reach their full growth potential and is defined as a child’s height being too low for their age.

Wasting, or acute malnutrition, is the most life-threatening form of malnutrition and indicates that a child’s weight is too low for their height.

45 million

Wasting—generally considered a more acute form of malnutrition than stunting—threatened the lives of an estimated 7% or 45 million children under five globally in 2022. Evidence points to low maternal body mass index as the leading factor associated with wasting in older children 12 to 59 months of age.

20%

Stunting affected an estimated 22% or 148 million children under five globally in 2022. An estimated 20% of stunting begins in utero.

2.9 times

Children 12 to 59 months of age who were born with low birth weight in low- and middle-income countries are approximately 2.9 times more likely to develop stunting and are at a 2.7 times higher risk of wasting compared with those born with normal birth weight.

Partners

Learn More

Ask an Expert

Our team and partners are available to answer questions that clarify our research, insights, methodology, and conclusions.