COVID-19 RESPONSE AND MAINTENANCE OF ESSENTIAL HEALTH SERVICES IN THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

CONTENTS

QUICK DOWNLOADS

KEY INSIGHTS

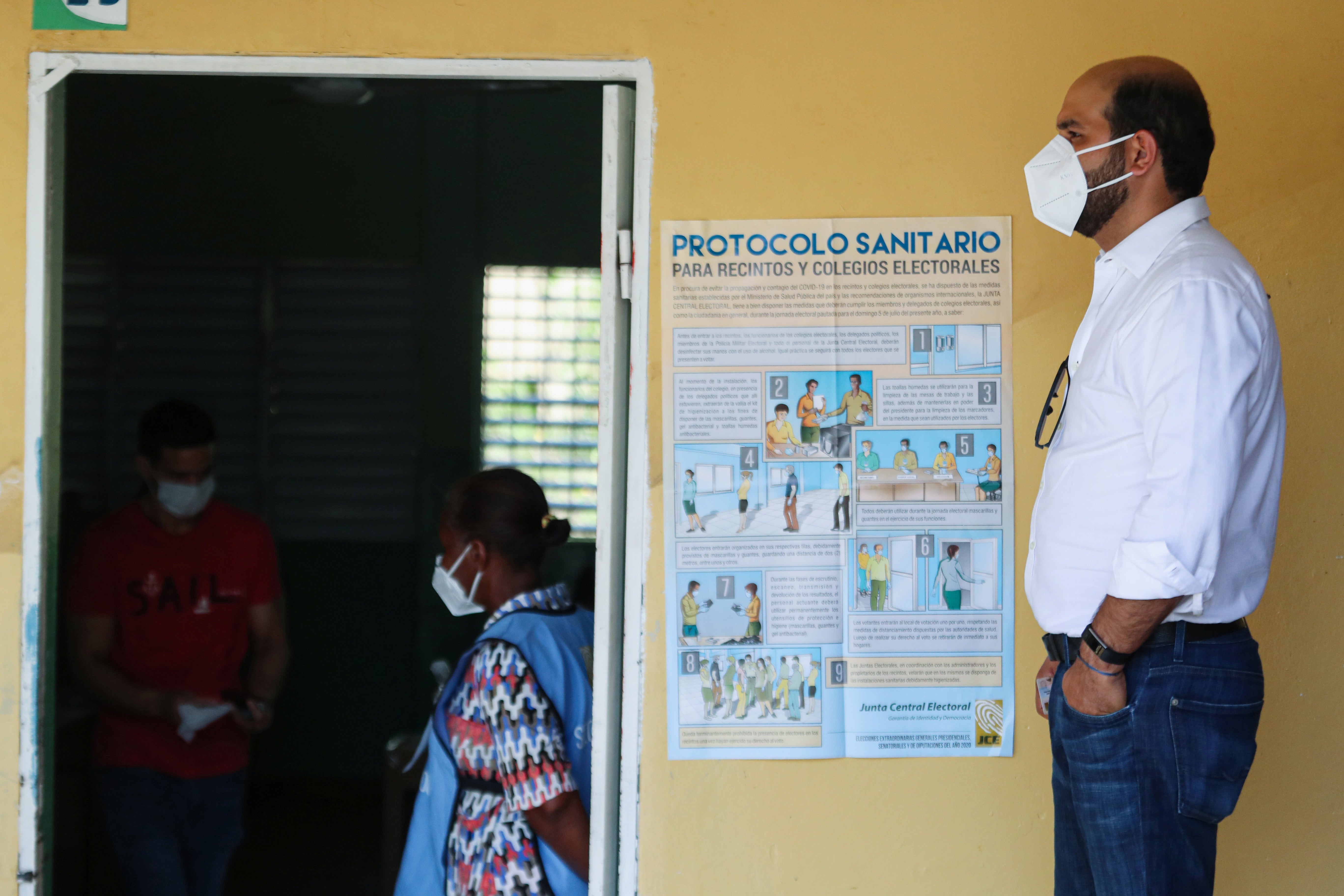

One of the challenges faced by the Dominican Republic at the beginning of the pandemic was the postponement of the national election, which was originally scheduled for May 2020. By the time Election Day happened in early July 2020, the country was among the hardest hit in the Caribbean, with more than 37,000 confirmed cases and 800 deaths from COVID-19 (Average for the Caribbean was about 6,000 confirmed cases and 150 deaths from COVID-19). The new government prioritized COVID-19 response and embraced policies— such as mass testing and vaccination for the whole population, free coverage and treatment for severe cases—that would keep case counts low and enable the economy—and especially the tourist sector—to reopen.

This research has been led by partners at the Fundación Plenitud in collaboration with Brown University School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and was supported and funded by The Rockefeller Foundation and by the Exemplars in Global Health program at Gates Ventures.

Drivers of successful pandemic response

The World Health Organization and Global Health Security Agenda have developed useful frameworks for assessing epidemic and pandemic preparedness and response, which we have adapted for this research. Through our research, we aim to derive lessons learned about the drivers of a successful response and have developed a conceptual framework that categorizes the drivers into two groups: context and system factors and interventions, and also includes outcomes. The following pages on the Dominican Republic’s response to COVID-19 and the maintenance of essential health services are organized according to this framework.

What were the most important elements of the Dominican Republic’s COVID-19 response?

There are many challenges with conducting research during an evolving pandemic, including quality of data and availability of interviewees involved in the response. In the absence of true impact measurements, we used alternative metrics as proxy indicators and developed criteria to help identify best practices, including overall reach and access, repeated mentions in key informant interviews, innovative or adaptive responses, potential for scale and impact, and equity considerations.

Contextual factors: previous experiences with epidemics

Leveraging strategies and tools developed for previous epidemics

Almost every year, the Dominican Republic experiences an outbreak of dengue, and recently it has also faced disease outbreaks with epidemic potential such as Zika (2016-2017) and Chikungunya (2014). Consequently, officials have experience creating outbreak preparedness and response plans—including one for chikungunya, which was the first of its kind in the Americas —and communication plans aimed at the public in general and high-risk groups in particular.

The Dominican Republic is also an island country vulnerable to Atlantic hurricanes and other extreme weather events associated with climate change. Officials, health workers, and citizens have learned to adapt to these risks through a set of emergency response tools, which they could leverage during the COVID-19 pandemic.

National, governmental, and population-level measures: public assistance and risk communication

Building trust to support adherence to public health measures

Government and health officials in the Dominican Republic invested considerable time and effort building trust in local communities and among health workers through clear communication, social protection measures, and use of government resources. Their aim was to ensure the rapid uptake of public health interventions.

The Dominican Republic used extensive risk communication methods and platforms to communicate with the public about guidelines, available resources, and government support. Social protection measures, including financial support programs and the extension of health insurance to 98% of people in the Dominican Republic, inspired public confidence in the government’s intentions and may have helped galvanize broad support for other policies aimed at mitigating the pandemic’s spread.

Interviews with key informants suggest this work paid off and may have boosted public support for and compliance with public health and social measures. In addition, health workers were “willing to face anything, even to give their lives, to be there during the pandemic and working on the front lines,” even as their jobs grew more demanding and dangerous, according to a key informant.

Health system-level response measures: facilities and infrastructure

Providing essential resources and funding for COVID-19 response through public-private partnerships

Alliances between the Dominican Republic’s public and private sectors contributed to mass testing and vaccination campaigns and boosted hospital capacity, which prevented system saturation during pandemic surges.

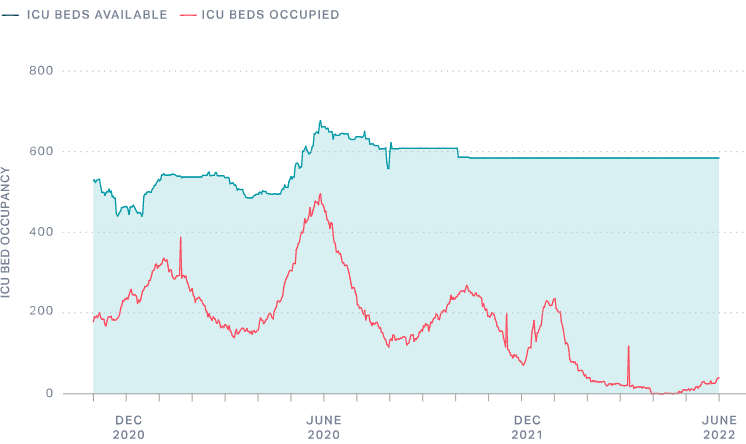

For example, public–private partnerships with the country’s private laboratory system enabled the government to substantially increase testing capacity. Additionally, agreements with insurers allowed the government to offer free testing to the entire population. Collaboration between the public health system and private hospitals also helped increase the number of available beds in intensive care units nationwide. Similarly, the health system was able to avoid exceeding hospital bed capacity—for COVID-19 and intensive care patients—through collaborations with the government and private hospitals, real-time monitoring of available resources and the use of the Ministry of Defense’s Command, Control, Communications, Computers Cybersecurity and Intelligence Center (C5i) which worked in collaboration with the National Health Services to construct a platform for surveillance . The successful implementation of the Dominican Republic’s vaccination plan also benefited from early key investments and support from the private sector.

National, governmental, and population-level measures: vaccination for the pandemic pathogen

Mobilizing the entire country toward a common goal

After the new president and administration were elected in August 2020, they mobilized the country toward a common goal: to protect the population through mass vaccination while gradually reopening the economy. Collaboration with the private sector made it possible to place orders for early vaccine doses through bilateral deals with pharmaceutical companies, Pfizer and AstraZeneca. On February 15th, 2021, the country received its first batch of COVID-19 Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines and on February 23rd they received a batch of Sinovac vaccines.

The Dominican Republic made use of existing programs—such as the Expanded Immunization Program in partnership with the VacúnateRD digital platform—to provide information about COVID-19 vaccination programs, including the location of vaccination centers nationwide, digital vaccination certificates, vaccination statistics, and an information line on the National Vaccination Plan (*822). Several private companies also provided space for vaccination centers, and others offered refrigerated spaces (such as trucks loaned from beer or milk distributors) to ensure the proper storage and distribution of vaccines.

In July 2021, the Dominican Republic became one of the first countries in the world to recommend a third dose (i.e., booster) as a matter of public policy., As of May 2022, 77% of the population over 18 years of age had received their first dose and 66% had received two doses.

COVID-19 RESPONSE AND MAINTENANCE OF ESSENTIAL HEALTH SERVICES IN THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

Ask an Expert

Our team and partners are available to answer questions that clarify our research, insights, methodology, and conclusions.