Executive summary

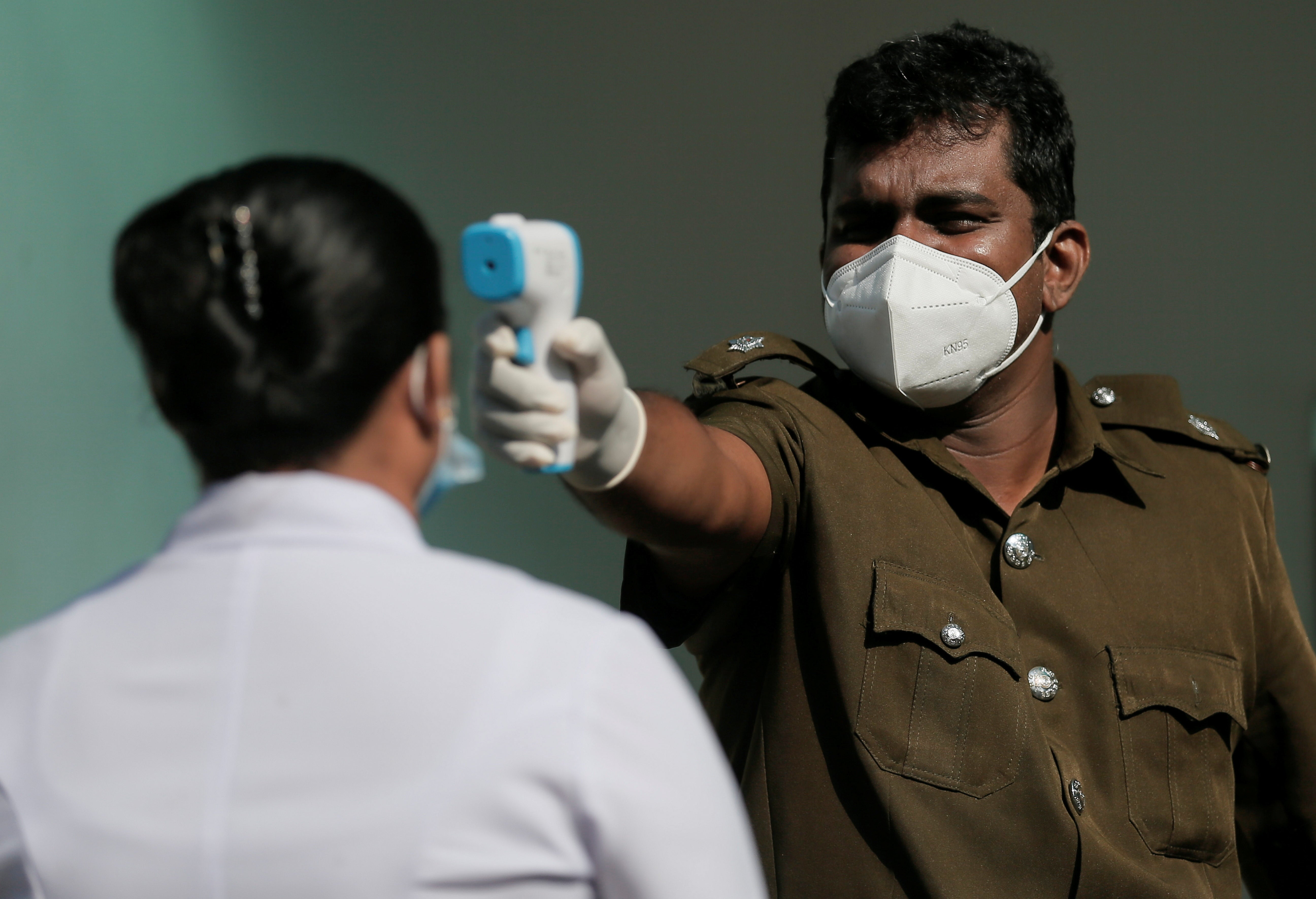

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, Sri Lanka had a strong initial response, with health authorities acting quickly to keep the novel coronavirus from spreading. They screened and quarantined travelers from abroad and implemented intensive contact tracing and isolation for all suspected patients to prevent local outbreaks. For months, the country avoided sustained local transmission and protected its health services from substantial disruption. However, without adequate ramping up of surveillance—including high levels of testing for symptomatic individuals in the community—local transmission went undetected for too long, enabling widespread transmission.

Sri Lanka’s experience illustrates two key lessons. First, limiting transmission of the pandemic pathogen is essential to avoid disruption to essential health services during an epidemic. Second, a well-managed health system like Sri Lanka’s, that prioritizes equitable access to care, will be more resilient in the face of major disruptions such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

How did we select the countries we studied?

Differences in testing, surveillance capacities, and reporting criteria have made it difficult to quantify and compare the impact of COVID-19 in countries around the world. Yet some countries were able to strengthen and sustain health system capacity, maintain essential health services, and target public health and social measures to mitigate the overall impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Identifying the strategies, policies, and practices that enabled these successes can give us a better understanding of health system resilience, adaptive health policies, and emergency response strategies that could be applied to other countries and future infectious disease outbreaks.

To select positive outlier countries with transferable lessons for pandemic preparedness and health system resilience, we used data from March 2020 through the end of 2020 to identify countries with best-practice responses to the early phases of the pandemic. This snapshot in time does not account for subsequent waves of the pandemic, nor for the later availability of COVID-19 vaccines in the selected countries.

The six countries were selected by evaluating COVID-19 indicators (including age-standardized deaths, cases, and testing) and essential health services indicators (including disruption to routine immunization) after screening for the availability of high-quality data and the transferability of the findings. After identifying potential Exemplar countries, we completed validation research including an examination of the COVID-19 epidemiological curve over time, testing policies and strategies, interventions to maintain essential health services, survey data, and interviews with local and regional health experts. The final six countries were selected after considering linguistic, demographic, and geographic diversity as well as government structure and data availability (see figure below).

Country Selection Methodology

For Sri Lanka and the other five selected countries (Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ghana, Thailand, and Uganda), we conducted a literature and policy review, key informant interviews, qualitative analysis, and quantitative analysis. We synthesized findings to develop key recommendations on health system resilience and pandemic preparedness. This country selection process reviewed indicators through the end of 2020, but the Exemplars research itself covers the time period through the end of 2021. It is important to note that the performance of the selected proxy indicators does not reflect the entire health system’s performance.

Several key interventions, summarized below and detailed in the following sections, contributed to Sri Lanka emerging as a positive outlier in the COVID-19 response and the maintenance of essential health services.

Quick early action

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, from March to September 2020, Sri Lankan authorities suppressed transmission in the community by enforcing quarantine and screening procedures at border points of entry, and implementing aggressive contact tracing and isolation for detected local cases. The success of this kind of elimination strategy, however, depends on high levels of symptomatic testing, and the Sri Lankan health system did not invest in strengthening its testing capacity in time to block sustained viral transmission in 2021.

Rapid and equitable vaccine delivery

Sri Lankan health authorities built on existing strengths of the country’s health system—high vaccination rates and high levels of public trust in vaccines—and acted quickly to vaccinate the country’s adult population in 2021, assisted by mobilizing support from the military for logistics and delivery. This rapid vaccination campaign began by purchasing large volumes of vaccines from India and then China, and was slowed only by limited vaccine stocks and was highly equitable, with no substantial disparities in coverage or speed of uptake between people of different socioeconomic status, ethnicity, or gender. This equitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccines throughout the country was a unique strength of the Sri Lankan vaccination program enabled by public financing and delivery of the vaccines, as well as by the mobilization of military support in expanding coverage. Uptake of boosters has been relatively slower, however, as of December 2021.

Service delivery adaptations

From the first lockdown in March of 2020, Sri Lanka’s health officials took proactive measures to maintain the supply of medicines for patients with chronic diseases, introduced protocols to minimize COVID-19 transmission in health facilities, and found new uses for existing telehealth technologies.

Challenges

Sri Lanka faced challenges in maintaining its local elimination strategy in 2020 primarily because it did not invest in strengthening capacity for COVID-19 testing at the primary care level. This may be attributed to a wider phenomenon of “groupthink” (conformity and consensus in decision-making) observed among official decision-making bodies, which prevented consideration of alternative views on testing and disregarded technical expertise from outside the government. Other factors that contributed to the spread of COVID-19 in 2021 included complacency following the initial success of the strategy, a medical culture that was generally averse to testing in clinical practice, and an environment of fiscal scarcity (exacerbated by tax cuts in 2020). Additionally, given the political unrest and economic instability throughout the pandemic and through 2022, public distrust in the government likely exacerbated these issues.