The Exemplars in Global Health program would like to thank Chuck Slaughter, Emilie Chambert, Edward Zzimbe and Patrick Yowasi Kadama from Living Goods, and Isaac Holeman from Medic for their contributions to and review of this report.

In this case study, we describe the implementation story of Smart Health in Uganda and its adaptation for the COVID-19 context. At end, there is an assessment of performance against the .

Introduction

In 2001 the government of Uganda enlisted community health workers (CHWs) known as Village Health Teams to bring high-quality health care to as many communities as possible. CHWs help by encouraging the adoption of healthy behaviors in communities where they live and reducing the burden at centralized health facilities where staff shortages are common. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the country’s health system was stretched: Uganda has only one doctor for every 17,000 people, fewer than the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation of one doctor for every 1,000 people. CHWs have helped contribute to improved health outcomes in Uganda, where preventable diseases such as malaria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis account for more than half of morbidity and mortality.,

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the nonprofit social enterprise Living Goods recruited, trained, and employed CHWs to provide health services with minimal interruption while responding to a surge in demand from Uganda’s overburdened health system. A key factor enabling CHWs to respond to this surge was the Smart Health app, a digital health management tool carried by each of Living Goods’ over 7,800 CHWs.

The Smart Health app guides CHWs through routine diagnostics and processes, with specific workflows for providing care related to pregnancy, childhood diseases, nutrition, family planning, immunization tracking, and most recently COVID-19. Workflows are automated and intended to increase CHW efficiency and accuracy. The Smart Health app also provides task lists and notifications to help CHWs prioritize patient visits and follow-ups. All data—including every patient interaction along with household data and health records—is captured and pulled automatically into performance dashboards that supervisors and government stakeholders can analyze. The app is becoming increasingly compatible with the Ugandan government’s District Health Information Software 2 (DHIS2) system.

As the demand for decentralized health services increased in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, Living Goods was able to quickly adapt and enhance the Smart Health app’s functionality due to its existing scale and flexibility and because it was already familiar to CHWs. New tasks and care protocols such as no-touch workflows, remote supervision, and user-facing COVID-19 messaging helped the company protect its CHW workforce from the novel coronavirus and maintain existing services while managing surges in demand from an overwhelmed health system. Early evidence suggests that these changes helped prevent health outcomes from worsening in Uganda, which may have otherwise happened during the pandemic as the health system was overloaded. In fact, Living Goods estimates that the adapted Smart Health app saved thousands of lives during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key Takeaways

- A modular digital design that was adaptable to changing needs enabled Living Goods to modify the Smart Health app, incorporate COVID-19 protocols, and resume service without having to overhaul its entire digital identity.

- App developers aimed for usability and simplicity in design, especially when adding new functionality, keeping in mind the CHWs with the lowest technological literacy. At times, features that could be included in the app, such as e-learning, were developed on separate platforms to maintain usability for these users.

- Existing investments in digital infrastructure, including an in-house development team, enabled Living Goods to make its own workflow adjustments without relying on an external technology company, saving crucial time and minimizing risks to its CHW workforce.

- Living Goods was able to react rapidly to government needs at both the district and national levels—it loaned staff to work directly at the Ministry of Health to fill capacity gaps, worked closely with government teams on COVID-19 protocols and guidelines, and provided communications support to CHWs.

- Real-time data collection gave Living Goods supervisors and government decision makers a view on emergent trends that could trigger quick changes to protocols and policy.

Smart Health Apps in Uganda Before COVID-19

Living Goods began operating in 2007 as a nonprofit social enterprise, aiming to create an entrepreneurial network of CHWs in Uganda that provide basic health care and information to families living in rural regions. Its CHW workforce goes door-to-door registering pregnancies and diagnosing malaria, diarrheal disease, and pneumonia. The CHWs also sell health products such as artemisinin-based combination therapy, antimalarials, clean cooking stoves, and fortified foods. Living Goods currently supports more than 7,800 CHWs in Uganda.

In 2014, the CEO of Living Goods approached Medic (then called Medic Mobile) about developing an integrated Android app that could be scaled to the organization’s entire CHW workforce. It would involve merging an existing suite of mobile apps that Living Goods had been using to digitize household registrations and adding automated workflows for basic care and built-in performance dashboards. Medic received unrestricted donor funding for the project, which enabled its developers to try innovative design approaches and conduct extensive user testing.

In the process of building the Smart Health app, which was introduced in 2015, Medic developers spent several weeks on the ground with Living Goods supervisory staff and CHWs, learning about workflows and identifying essential infrastructure and potential challenges. For instance, Medic developers used simple drop-down menus to restrict data entry in order to streamline workflows, promote ease of use, and limit user error. Developers also built the app to function in low-connectivity areas. Data entered in a CHW’s smartphone syncs automatically with servers as soon as an internet connection becomes available (or at monthly meetings).

Development of Smart Health by Medic

Medic, formerly called Medic Mobile, is a nonprofit health-technology company based in San Francisco. Medic’s digital tools help the community health workers (CHWs) who deliver care in the hardest-to-reach places provide effective and efficient care management through targeted task lists, digital patient profiles, messaging, and diagnostic decision support. They also compile performance and health data automatically into dashboards for analysis by supervisors and health system managers. Currently, Medic supports more than 27,000 CHWs in 14 countries.

Medic designed Smart Health in 2015 as a modular Android app with customizable workflows, leveraging the existing architecture of Medic’s open-source Community Health Toolkit Core Framework. Since its initial development, Medic has continued to develop the tool. In 2016, Medic updated the app with Equity Tool, which allowed LG to examine equity data alongside health data to understand inequities in service delivery, and in 2018, Medic added predictive algorithms to help identify the populations most in need. More recently, Medic and Living Goods have been working to develop data systems that are fully compatible with DHIS2 in in Uganda.

Smart Health’s key features include:

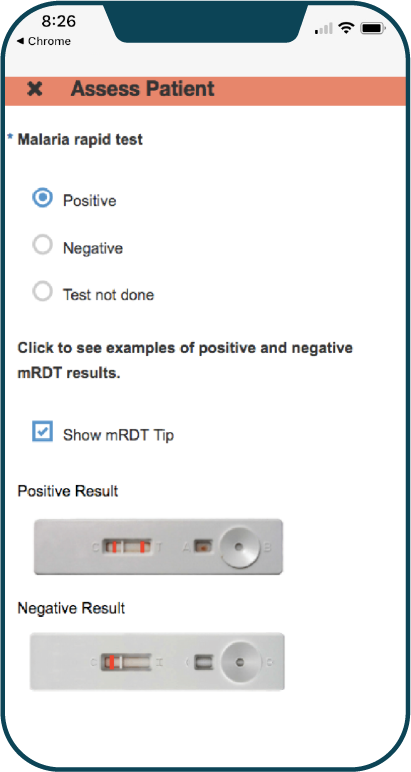

- Smart workflows: Smart Health’s automated workflows guide CHWs through patient health assessments, helping them to accurately identify and diagnose illnesses and dangerous pregnancies and make referrals to local and regional health facilities.

- SMS: When a CHW logs a pregnancy, birth, or treatment in the app, the household is auto-enrolled in SMS messaging for content and reminders related to treatment and care.

- Data-driven task list: The Smart Health app uses live patient and census data and artificial intelligence to create predictive daily task lists that help CHWs prioritize time for patients with the highest risk of health problems. This predictive capability improved CHW population-coverage methods, which previously relied on geographic canvassing.

- Real-time performance management: Because the Smart Health app captures every patient interaction in real time, supervisors and government officials can monitor CHW performance against set key performance indicator targets, spot disease outbreaks, recognize high-performing CHWs, and prioritize CHWs in need of managerial support.

- DHIS2 interoperability: Smart Health gives the government access to real-time data dashboards that are standardized and integrated with DHIS2. Living Goods has provided real-time data on health outcomes for the Kenyan government since 2019 and is currently working on similar integration in Uganda.

Smart Health App used to diagnose malaria

The Path to Scale and Sustainability

In 2014, Living Goods employed about 1,000 CHWs in Uganda, who covered more than 800,000 people in their communities. The integration of the Smart Health app in 2015 was part of a larger effort to aggressively scale up the organization’s operations in Uganda, by expanding the size of its CHW workforce, the number of people covered by its services (from 1.5 percent of the Ugandan population to 5 percent ), and the range of health-related services offered. The expansion plan also involved scaling operations to neighboring Kenya.

By 2018, Living Goods’ workforce had grown to include 7,000 CHWs serving more than 5.6 million Ugandans. That same year, Living Goods concluded a joint pilot program with the government of Uganda to introduce new family planning workflows to the Smart Health app. Good results from the pilot led to the rollout of family planning services across Uganda.

Living Goods invested early in a randomized controlled trial evaluation to measure the impact of its model on maternal and child mortality in Uganda, and 2014 results showed a 27 percent reduction in under-five mortality after three years, at an estimated cost of US$68 per life saved. Although the organization has yet to conduct a randomized controlled trial of its model using the Smart Health platform, it has seen dramatic increases in key health performance indicators across its operations in Uganda. Treatments provided to children under the age of five increased from 62,000 in 2013 to more than 1.6 million in 2020.

Year-End Key Performance Indicators, 2020

Living Goods Quarterly Reports. Living Goods website. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://livinggoods.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Q2_2020-Report-.pdf

Adapting to a New Challenge

The COVID-19 pandemic has tested Living Goods’ overall capacity, resulting in changes to its operating model. Living Goods sought to protect its CHW workforce from COVID-19 by adding functionality through the Smart Health app and developing protocols for distanced and remote care. It has done this while also maintaining its existing range of services, managing the surge in demand from an overwhelmed health system, and helping to disrupt the transmission of COVID-19. For example, Living Goods took emerging guidance from the World Health Organization and other technical experts to adapt the delivery of health services under adjusted no-touch and low-touch protocols. Living Goods then used these protocols as guidelines to shape no-touch workflows added to the Smart Health app to ensure safe conduct for CHWs. These new workflows transitioned the majority of maternal and child health services to virtual telehealth engagements while providing personal protective equipment and risk guidelines for services that must be rendered in person.

The technical challenges of implementing no-touch workflows were immense. The internal development team had to make fundamental changes to each of the existing workflows, more than 30 in total, on a vastly accelerated timeline (even small changes to one workflow usually took more than two weeks). The full transformation involved reconfiguring the software, rolling out a new version of the app, and communicating the changes to CHWs—which took about one month in total. A senior manager for Living Goods in Uganda commented on the rollout: “Given the scale of the changes needed within the time frame required, the fact that we got this done was nothing short of a miracle.” The specific technology changes involved two primary areas:

- Safety procedures for in-person checkups. Before every in-person patient interaction, the Smart Health app would run the CHW through a personal safety and equipment check as well as a COVID-19 self-assessment.

- Health program adaptations. The adapted workflows clearly differentiated which procedures would happen by phone rather than in person, erring on the side of presumptive diagnosis and treatment for certain diseases (e.g., malaria). An entirely new workflow was created for COVID-19 case management. For suspected cases, the app triggered three stages of follow-up, in line with the Ugandan government’s protocols. Finally, the app also supported the distribution of free medicines—Living Goods historically has not provided free medicine, but it did so temporarily to sustain provision of services. Receipts and dosages were tracked through the app.

New models for monitoring CHW performance—including remote supervision, peer supervision, and easy-to-read performance dashboards on the Smart Health platform—have improved quality and cost-effectiveness while ensuring compliance with low- and no-touch COVID-19 protocols. For instance, in 2020, Living Goods found that high-performing peer CHWs can replace the work of a paid supervisor, which has reduced supervision costs, improved efficiencies, and increased CHW performance outcomes by up to 20 percent. Peer supervision is an example of a rapid change that typically would typically call for a longer pilot period during non-crisis circumstances but could help to quickly scale up operations in other countries going forward by reducing the size of the supervisor level workforce.

Digital tools for Living Goods’ CHWs were also complemented by a messaging platform with four major features: (1) one-way messaging to CHWs in catchment areas, (2) messages about provision of care, (3) integration with the Ministry of Health’s reporting system for COVID-19 cases (suspected cases and their contact information would be forwarded to the Ministry of Health), and (4) an SMS system integrated with the government's SMS platform for [communicating about] COVID-19.

Even before the pandemic, Living Goods cultivated close partnerships with the Ugandan government, including fostering a relationship with an early champion of its approach. Since 2017, LG Electronics has been asked by the Ministry of Health to contribute to several high-level working groups and offer direct input into the country’s community health financing strategy. LG has also cultivated strong partnerships with other CHW-focused organizations to share its digital approach. Through the Audacious Project, CHWs supported by Last Mile Health in Liberia were equipped with the Smart Health app and received digital training through the new Community Health Academy. Living Goods also contributes to the Community Health Impact Coalition along with 11 other organizations (Amani Global Works, Integrate Health, Last Mile Health, Lwala Community Alliance, Medic, Muso, Partners in Health, Pivot, Possible, VillageReach, and VITAL Pakistan) to develop evidence and best practices for community health interventions. When the COVID-19 pandemic began, Living Goods loaned more than a dozen staff with nursing backgrounds to support Uganda’s COVID-19 hotline and two senior-level technicians who worked directly at the Ministry of Health. This has presented an opportunity for the organization to deepen its partnership with the government and help shape the latest COVID-19 protocols while demonstrating the value proposition of the LG model to address the demands of the pandemic and other health emergencies.

Timeline of Key Events

Impact

The modified Smart Health app, equipped with new no-touch protocols, has enabled Living Goods’ CHWs to continue their work remotely with minimal interruption and without compromising the quality of care. Living Goods stands out from other CHW organizations that did not have similar digital capabilities and were forced to scale down their operations during the pandemic lockdown. For most others, mid-2021 was the projected time when service provision could start up again. LG also covered the costs of distributing essential medicines to communities suffering from economic hardship due to the lockdown to ensure continued care.

Early evidence suggests that the modified Smart Health app helped prevent health outcomes in Uganda from worsening, which may have otherwise happened during the pandemic as the health system was overloaded. A review of government data in Kenya and Uganda revealed up to 35 percent declines in the number of people who sought facility-based care and treatment for common childhood diseases such as malaria, diarrhea, and pneumonia during the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, Living Goods saw treatments and referrals for the same diseases nearly double from 2019 to 2020 in the parts of Uganda where they support CHWs. For example:

- The number of treatments and referrals CHWs provided to under-five children per month spiked 90 percent.

- CHW treatments or referrals for malaria increased 138 percent in malaria-endemic areas (partly due to presumed diagnoses).

- CHW treatments or referrals for pneumonia increased 62 percent and for diarrhea increased 46 percent.

- The number of children completing vaccinations increased 3 percent in CHW catchment areas, despite expectations of decline.

On the whole, Living Goods estimates that it saved 9,000 more lives in 2020 than in 2019, nearly doubling its impact during the pandemic.

COVID-19 Response Launch in Uganda and Kenya

Story of Impact: Community health saved lives during the crisis. Living Goods website. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://livinggoods.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Q2_2020-Report-.pdf

What Were the Key Drivers of Scale?

- Groundwork – Human-centered design and unrestricted funding: Unrestricted donor funding enabled Medic to collaborate with end users to design solutions tailored to Living Goods’ needs, and their focus on a modular app has ensured its continued usefulness.

- Technology & Architecture – Keeping the Smart Health app lean: Especially when adding new functionality, developers from both Medic and Living Goods have been careful not to overcomplicate the interface to simplify it for users, at times choosing to exclude functionality.

- Operations – Investing in tech infrastructure: Living Goods made holistic technology-related investments that were necessary for integrating and sustaining the Smart Health platform, including regular training for its CHWs, IT support staff, and an in-house team of developers to roll out new workflows and features.

- Partnerships – Government partnerships and partnerships with other CHW organizations: During the COVID-19 pandemic, Living Goods continued to build on the long-standing relationship with Uganda’s Ministry of Health by adapting the app to government needs and loaning staff to the ministry.

- Technology & Architecture – Making use of Smart Health data: Living Goods relies on its ability to demonstrate its impact and measure performance, and the Smart Health app’s back-end design enables them to easily pull and examine their data.

What Implementation and Scaling Challenges Remain?

- Financial Health – Challenge with financial sustainability: In 2018, Living Goods launched an innovative results-based financing mechanism in Uganda, enabling funders to “buy outcomes” related to health priorities (e.g., malaria treatments provided or births occurring in health facilities). The mechanism generated greater investment and demonstrated to the Ministry of Health and global donors the viability of a pay-for-results model for community health services. Its success paved the way for co-financing partnerships directly with county and national governments. As a result, Living Goods’ long-term financial sustainability hinges on the success of its co-financing partnerships, first piloted with county governments in Kenya and now being deployed in Uganda. In November 2018, Living Goods and Kenya’s Isiolo County Government signed a four-year contract in which the government will outsource operations to Living Goods. The government will pay Living Goods to refine and implement its model in Isiolo, with the eventual goal of transitioning ownership to government. Without long-term financing in place, however, Living Goods’ future will remain uncertain.

- Technology & Architecture – Interoperability challenges: The Smart Health DHIS2 integration in Uganda has been slower to launch than in nearby Kenya, and despite a memorandum of understanding signed with the government, the integration faces continued roadblocks.

Conclusion

By adapting its flexible, modular Smart Health app to the urgency of the COVID-19 pandemic, Living Goods saved lives and learned valuable lessons it can apply to future health emergencies. The team is better prepared to keep people safe from communicable disease and has demonstrated the importance of an adaptable operating model.

Meanwhile, since 2018, Medic has shifted the focus of its operations to maintaining and refining an open-source version of its core framework technology, the Community Health Toolkit, which can be adapted by local developers, without on-the-ground design support from the Medic team. Medic is gradually moving toward an advisory model by strengthening the capacity of local teams to design their own apps using the Community Health Toolkit and manage their own deployments. Medic also focused on cultivating a community of practice, where users around the world can share insights and seek guidance from other users, while interacting with Medic’s technical team. With these tools, CHWs can continue to improve health outcomes in hard-to-reach, underserved places.

Assessment of the Smart Health app in Uganda across the MAPS framework

This is a qualitative assessment based on the mHealth Assessment and Planning for Scale framework. To learn more about the framework, .