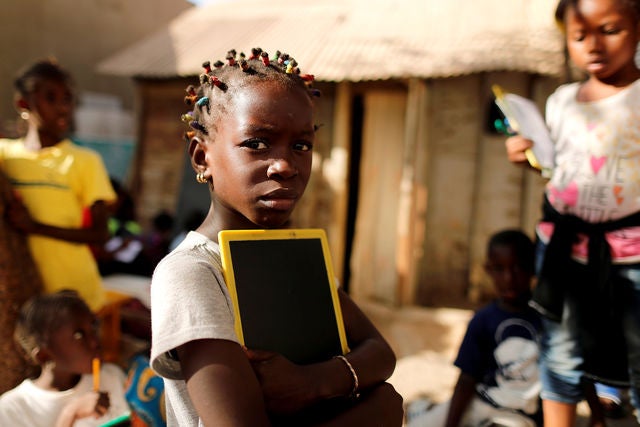

244M children out of school, including 50M girls in sub-Saharan Africa: UNESCO

Countries are rallying to keep girls in school to reap the rewards of increased education, women’s empowerment, and better health

Some 244 million children between the ages of six and 18 worldwide are currently out of school, UNESCO has announced. Overrepresented are sub-Saharan Africa's girls – 50 million of whom are out of school. This is more than the total of out of school girls from any other region, and the number is growing.

The crisis in girls’ education is, in part, the result of COVID-related school closures that pushed many rural and low-income girls into early marriage, motherhood, or work to support their families. “Even when schools have reopened, millions of girls in sub-Sharan Africa have not gone back to school,” said Caroline Ngonze, of the UN’s Education Plus Initiative in an interview earlier this year.

In response, UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay will call on world leaders to ensure the right of all children to education is supported and respected at the Transforming Education Summit convened by the United Nations later this week. Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai will sound a similar theme, with a focus on girls’ education, at the annual Goalkeepers event on September 21.

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa and beyond are also moving to support girls' education, including by revoking old policies that prevented teen mothers from continuing their schooling.

Cameroon, for example, amended national regulations in April to allow pregnant girls to attend school. “For many decades, pregnant young girls in Cameroon have not been allowed to stay in school,” wrote Emelyne Calimoutou, a senior legal and gender specialist at the World Bank. “School administrators and other community members considered them poor examples for others, and often these girls were dismissed from school, permanently. Unsurprisingly, this resulted in high dropout rates and fewer opportunities for young girls to live healthy and productive lives.”

A couple of data points help explain why ensuring pregnant girls can continue their education is critical: about 10 percent of girls in Cameroon marry by the time they turn 15 and 30 percent marry by the time they turn 18. Cameroon’s shift follows nearly a flurry of new policies and programs across sub-Saharan countries, including Mozambique, Niger, Sierra Leone, São Tomé e Príncipe, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, and Zimbabwe, where there are new aims to revoke similarly discriminatory and self-destructive policies.

The change in Niger was part of package of policies passed in 2019 to prevent child marriages, and illustrates the potential impact of this shift. The country has the highest rates of early marriage and childbearing in the world – 76 percent of teen girls marry by the time they turn 18, according to UNPF. Until the 2019 reform, a 1978 rule barred married girls and all pregnant girls from attending school – effectively prematurely ending the education and ambitions of a majority of the country’s daughters. Niger’s President Mohamed Bazoum, who will be attending and speaking at next week’s Goalkeepers event, has made girls' education a central focus of his administration.

Other countries working to address the challenge include Jamaica, which has focused on psychosocial and financial support to ensure that pregnant girls stay in school. With mentorships, scholarships, and other types of support, the country has sought to reduce the chance adolescents fall pregnant again and drop out of school permanently. Ten centers around the small island nation help ensure girls receive the health care and contraception they need to be healthy mothers while continuing their education. “These mothers, their place remains in school,” said Zoe Simpson during a webinar earlier this year. “They have a right to education.”

Jamaica’s model has been replicated in other countries, including Grenada, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Botswana, The Gambia, and Kenya.

The issue is particularly urgent following the pandemic's three years of closed schools and limited services, which helped cause a spike in teen pregnancies in Africa and elsewhere. For example, between April 2020 and March 2021, South Africa saw a 60 percent increase in adolescent pregnancies, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

A wealth of global research demonstrates that educating girls is not only important for their human rights, but it powers individual and national economic growth and has a protective effect for the girls’ individual health and the health of their children.

Winnie Byanyima, the Executive Director of UNAIDS and Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations, noted in an Exemplars in Global Health Perspective article last year about the strides Botswana is making in expanding education for girls that: “For girls, each additional year of schooling resulted in the risk of contracting HIV dropping by 11.6 percent. By expanding free and compulsory secondary education, Botswana produced a cumulative lifetime risk reduction for HIV among students of approximately one-third.”

Exemplars in Global Health research is also rife with examples of countries that have reduced school fees, increased the number of years of required education, and launched conditional cash transfers to improve girls’ educational outcomes, reaping knock-on benefits in other areas. Researchers have confirmed, for example, the pathway from education to stunting reduction: that better educated parents earn more and are better able to provide for their children, and better educated mothers are better positioned to understand, advocate for, and follow health and nutrition best practices.

In Ethiopia, health leaders were able to reduce childhood stunting levels from 67 percent to 37 percent from 1992 to 2019, in part through improving both access to and quality of education. Since the early 1990s, the number of primary schools in Ethiopia tripled, enrollment in primary school has quadrupled from only 19 percent in 1994 to 85 percent in 2015, and literacy more than doubled. Girls, who used to be underrepresented at all school levels, have achieved parity in primary school enrollment.

Nepal, likewise, implemented a string of policies to boost education. In 1990, primary school enrollment in Nepal was less than 70 percent and the literacy rate for girls was just 33 percent. But by 2016, after building new schools and enrolling more than a million more children in primary school, the country had achieved gender parity in primary school enrollment and near parity in secondary school completion.

These investments in education, combined with other investments in the health sector, helped Nepal reduce its childhood stunting rate from 68 percent to 36 percent from 1995 to 2016.

How can we help you?

believes that the quickest path to improving health outcomes to identify positive outliers in health and help leaders implement lessons in their own countries.

With our network of in-country and cross-country partners, we research countries that have made extraordinary progress in important health outcomes and share actionable lessons with public health decisionmakers.

Our research can support you to learn about a new issue, design a new policy, or implement a new program by providing context-specific recommendations rooted in Exemplar findings. Our decision-support offerings include courses, workshops, peer-to-peer collaboration support, tailored analyses, and sub-national research.

If you'd like to find out more about how we could help you, please click . Please consider so you never miss new insights from Exemplar countries. You can also follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn.