World on edge of eradicating Guinea worm disease

Despite there being no vaccine or cure, the number of cases has fallen from about 3.5 million in the 1980s to just a handful this year

Guinea worm disease is poised to become the second human disease in history, after smallpox, to be eradicated.

In 1986, when the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution to eliminate Guinea worm disease, there were approximately 3.5 million cases of the disease, which causes debilitating pain. Those cases were spread across 21 countries from Mauritania to India. By 2021, there were just 15 human cases – all of them in just four countries. This year, there have been just six cases, including five in Chad and one in South Sudan.

The remarkable success against the disease offers lessons for other health challenges and demonstrates how singularly focused eradication efforts can be leveraged and broadened to deliver essential health care and improve health outcomes in rural and remote areas.

The progress against Guinea worm is all the more noteworthy given there is no vaccine or cure for the disease – only preventive efforts to combat it. “With Guinea worm, we have no silver bullet,” said Makoy Samuel Yibi, the national director of South Sudan’s Guinea Worm Eradication Program. “There is no vaccine. We have only water filters and behavior change.”

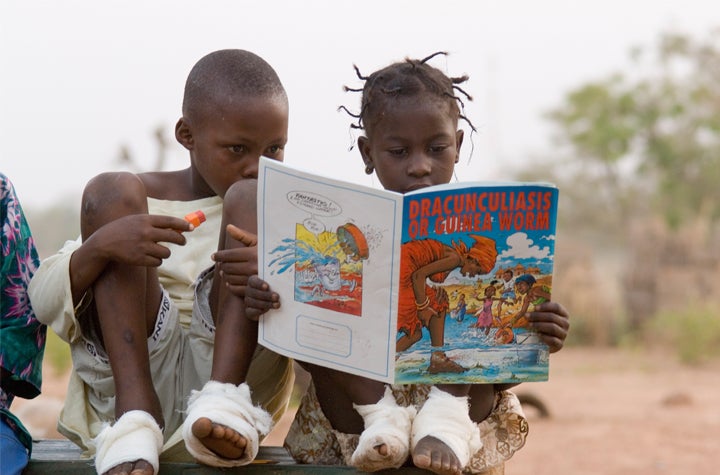

The disease has afflicted humans for thousands of years. People contract the disease by consuming water that contains tiny copepods (water fleas) that are infected with Guinea worm larvae. Once ingested by a human, those larvae mate and females grow into worms up to one meter long. About one year later, the worm begins to emerge through a painful blister on the skin, often on an individual’s feet or legs. The blisters burn and itch, which often motivates the infected person to seek relief by immersing their wound in water, where the worm then releases larvae to continue the Guinea worm’s cycle of life. The only treatment is pulling the worm slowly (often over the course of weeks or months) from the open wound. During that time and for weeks thereafter, the infected individual is often incapacitated, unable to work or study. For that reason, the Dogon people of Mali dubbed it “the disease of the empty granary” – it causes hunger, malnutrition, and starvation by incapacitating farmers.

Over the past four decades, the scourge has been eliminated in village after village across the affected countries through large-scale, bottom-up community mobilization efforts. One particularly effective tool for community mobilization has been annual “worm weeks” where local people organize plays and arrange ceremonies highlighting the importance of preventing the devastating disease and demonstrate prevention tools and strategies.

In fact, communities in endemic areas – many of them in the poorest and most insecure areas of the world – have been the backbone of the campaign. With support from their respective ministries of health, tens of thousands of communities have elected volunteers to lead robust monitoring systems and behavior change efforts. The volunteers, supported by village committees and supervisors, visit every household in their community once a day to identify cases, investigate suspected cases, inspect filters, educate, and prevent transmission by ensuring infected (or suspected) individuals do not enter water sources. Local area supervisors also help promote and demonstrate water filtering best practices and treat stagnant water with larvicide. In some endemic countries, volunteers and supervisors investigated tens of thousands of suspected cases within 24 hours of initial reporting each year.

The infrastructure required to support such robust and large-scale monitoring has not only connected rural and remote communities with national health systems, but also has helped strengthen national health systems in countries like South Sudan, the world’s youngest country, which previously had little to no functional system after decades of war and insecurity.

One unexpected hurdle towards eradication was the 2012 discovery in Chad, of dogs infected by the disease. The worms that infect animals are the same species that infect humans, and had previously remained undocumented.

"We didn’t see the dog infections right away,” said Adam Weiss, director of the Guinea Worm Eradication Program at The Carter Center, which has led the global eradication campaign since 1986. “We kept seeing human cases in different parts of Chad with no connection between the individuals. At the time, our surveillance system wasn’t designed to look for dogs or cats. But eventually, we figured out that dogs were spreading it.”

This has forced communities and health authorities to track, treat, and work to prevent not only human cases of Guinea worm disease, but cases in both dogs and cats as well. Dogs and cats often contract the disease by eating uncooked fish parts (containing Guinea worm larvae) discarded by fisherfolk. Now communities in endemic areas are educated and trained to bury fish guts to prevent the spread of the disease. Despite this added challenge, progress has continued.

This remarkable success story was hard won, said Weiss. After smallpox was eradicated, the global health community selected Guinea worm disease as the second human disease for eradication. At the time, health leaders worried that without a cure or vaccine, there was little chance of ending Guinea worm disease. But the devastating human and economic costs in endemic countries (in just three states in Nigeria, the economic cost was estimated to top US$20 million per year) prompted health leaders in many of the countries afflicted by the disease, supported by the The Carter Center and many partners including the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, to vow to eliminate it and push the global health community to support their efforts. Progress, said Weiss, slowly gained momentum. “Each country that achieves elimination renews the dedication of other health leaders.”

A few factors make Guinea worm disease a strong candidate for eradication, despite the fact that there is no vaccine or cure. It is easily diagnosed by frontline health workers without the need for any technology, unlike, for example, malaria, which requires a blood test. It is seasonal and occurs mostly during and immediately after heavy rain seasons. There’s also been tremendous political at all levels to solve the issue. And there are key points in its lifecycle where it is vulnerable to interventions. Health leaders have exploited each of these vulnerabilities to achieve remarkable progress. For example, infected ponds can be treated with larvicide that leaves the water potable but kills the copepods. And simple and cost- effective cloth filters can be used to strain the Guinea worm-infected copepods from drinking water.

The Carter Center has also distributed tens of millions of personal drinking straws that can be worn around the neck, giving people the ability to filter their water no matter where they are – critical for populations who are nomadic, herders, or displaced as the result of conflict. Lastly, as governments expand access to safe water as part of broader water and sanitation efforts, the risk and reach of Guinea worm has dropped.

Most importantly, the parasite must pass through people or animals during its lifecycle, so when transmission to humans, cats, and dogs, is interrupted, there's now a chance it could be eradicated and become extinct forever.

How can we help you?

believes that the quickest path to improving health outcomes to identify positive outliers in health and help leaders implement lessons in their own countries.

With our network of in-country and cross-country partners, we research countries that have made extraordinary progress in important health outcomes and share actionable lessons with public health decisionmakers.

Our research can support you to learn about a new issue, design a new policy, or implement a new program by providing context-specific recommendations rooted in Exemplar findings. Our decision-support offerings include courses, workshops, peer-to-peer collaboration support, tailored analyses, and sub-national research.

If you'd like to find out more about how we could help you, please click . Please consider so you never miss new insights from Exemplar countries. You can also follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn.