India’s health system

Public health services in India are organized primarily within the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), as shown in Figure 19. Over the past two decades, delivery care has increasingly occurred at district hospitals, which are located in each district’s headquarters and typically serve about two million people. Particularly in more urban areas, government medical colleges and specialty / referral hospitals are increasingly becoming common places of delivery.,

Within districts, and especially in rural areas, a hierarchy of health facilities— comprised of community health centers (CHCs), primary health centers (PHCs), and health sub-centers (HSCs)—play a role in providing antenatal, delivery, and postnatal care. Across India, CHCs serve about 165,000 people on average, PHCs serve about 36,000 people, and HSCs serve about 6,000 people. In the private sector, for-profit facilities include multispecialty or specialty hospitals, nursing homes, and clinics, as well as nonprofit hospitals and clinics run by charitable organizations and NGOs., Recent evidence from India’s National Family Health Survey (NFHS) indicates that the vast majority of institutional deliveries in India occur in public facilities, limiting the private sector’s role in reducing neonatal and maternal mortality in recent decades.

The role of the private sector, as well as facility designation and structure, varies somewhat across states and across mortality clusters. Unique characteristics of health systems within higher and lower mortality state clusters are described in more detail in their respective narratives.

Figure 19: India’s health care system in the public and private sectors

Morampudi S, Balasubramanian G, Gowda A, Zomorodi B, Patil AS. The challenges and recommendations for gestational diabetes mellitus care in India: a review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017;8:56. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2017.00056

A series of national health policies, highlighted in greater detail in the next section, have continually prioritized improving the availability and quality of health facilities across India. The increase in availability of CHCs is particularly notable, with the most prominent expansion occurring during the 1997–2005 Reproductive and Child Health I (RCH I) policy period as shown in Figure 20. In line with this rapid expansion in CHC facilities, the percentage of deliveries occurring in CHCs increased from 3% in 2000 to 31% by 2018., In contrast, the density of PHCs and HSCs increased rapidly from the early to late 1980s but has plateaued in decades since. There tends to be a higher concentration of CHCs, PHCs, and HSCs in lower mortality states compared with higher mortality states, with gaps widening slightly across state clusters.

Figure 20: Trends in the density of community health centers (CHCs), primary health centers (PHCs), and health sub-centers (HSCs) in India and across state clusters

India Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW). Rural Health Statistics 2018-2019. New Delhi: MoHFW; 2019. Accessed September 10, 2024. https://ruralindiaonline.org/en/library/resource/rural-health-statistics-2018-19/

As each successive national health policy expanded and enhanced the country’s network of health facilities, concurrent efforts were also made to grow and strengthen the country’s health workforce. India’s health workforce has increased slightly in density over the past two decades, although more so for nurse/midwives than for doctors. Between 2005–2005 and 2017–2018, the density of nurse/midwives per increased from 7.1 to 10.9 per 10,000 people. During the same period, the density of doctors also increased from 4.3 to 5.9 per 10,000 people.

National health policy periods

Since 1992, India’s national health policy landscape has been comprised of four distinct periods of programming related to maternal and newborn health, as shown in Figure 21. While each period has contributed uniquely to India’s progress in reducing NMR and MMR, they have built on each other to contribute toward six interrelated trajectories of change. These include:

- Increasingly comprehensive health care with a pro-poor focus

- Community engagement and outreach

- Shifting childbirth from homes and traditional birth attendants to facilities and skilled birth attendants

- Improving the availability of health care facilities and health worker services

- Increasing access to evidence-based lifesaving technical services

- Improving the quality of services

Each policy period is expanded upon to describe how it contributed to the six trajectories of change. In particular, the Reproductive and Child Health II/National Rural Health Mission (RCH II/NRHM) policy period from 2005 to 2012 is described in additional detail due to significant improvements in key indicators observed during that policy window. An additional, more detailed timeline of key policies, programs, and events that have impacted maternal and newborn health is also provided in the section.

Figure 21: Timeline of India’s national-level health policy periods

Linking back to this study’s conceptual framework, shifts noted throughout this section generally represent distal and intermediate factors. The distal policy and health system levers are linked to changes in service delivery as intermediate levers. The program levers to improve service delivery operate downstream of those broader distal factors, but upstream of more proximate factors such as health service coverage and equity. Throughout this section, we highlight the consequences that these policy shifts had on proximate factors, referencing back to the section of this narrative synthesis.

Child Survival and Safe Motherhood Program (1992–1997)

While the Child Survival and Safe Motherhood (CSSM) program began in 1992, it was implemented in a phased manner and did not achieve coverage in all districts until 1996–1997. Key features of CSSM include a focus on routine immunization, family planning, and efforts to empower traditional birth attendants with additional skills as they cared for home births. While subsequent national health policies would expand in scope as India evolved, in describing the reach of CSSM, one government official said:

“The main focus was population, family planning, and there were of course the components of maternal health, child health, but it was very limited.”

Under CSSM, traditional birth attendants were provided with presterilized, disposable delivery kits and trained in obstetric care. Traditional birth attendants were also trained in aspects of ANC during CSSM, which at that time focused on tetanus toxoid injection, iron and folic acid supplementation, and high-risk pregnancy screening in an effort to reduce maternal tetanus and anemia. The aforementioned first referral units (FRUs) were created during CSSM, but were limited in their ability to achieve their intended impact due to a variety of factors, including the blood banking example described earlier. Similarly, filling the obstetrician-gynecologist, pediatrician, and anesthetist positions at the new FRUs was a challenge, especially initially during the CSSM period, limiting their immediate impact.

Reproductive and Child Health I (1997–2005)

The Reproductive and Child Health I (RCH I) period continued many of the core approaches seen during the CSSM period, including training traditional birth attendants to provide antenatal and delivery care as well as expanding contraceptive method mix.

RCH I introduced “safe motherhood consultants” who visited CHCs and PHCs for scheduled pregnancy termination and also provided training to doctors in techniques approved for medical termination of pregnancy. This set the stage for the government to release the medical termination of pregnancy (MTP) rules in 2003, which authorized registered medical practitioners to prescribe mifepristone and misoprostol for medical abortion up to seven weeks. This milestone served as an amendment to the 1971 MTP Act and aimed to increase the number of safe MTP providers by decentralizing the power to approve health facilities as MTP centers.

The RCH I period also saw continued efforts to expand health infrastructure, as the government sanctioned the construction of 1,243 new facilities and the renovation of another 2,500 buildings to add delivery rooms and operation theaters. With a renewed commitment to geographically equitable health services, many of the facilities were built in remote areas or in high-priority states generally within the higher mortality state cluster.

A strong political commitment to continued improvement helped facilities including FRUs evolve to become more effective at saving lives. For example, FRUs were initially not authorized to bank their own blood, but an amendment to the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules in 2002 allowed FRUs to establish blood storage units. Two years later, 24/7 on-site blood storage at FRUs was identified as a critical determinant of a facility’s functionality and capacity to deliver life-saving care.

Reproductive and Child Health II/National Rural Health Mission (2005–2012)

The Reproductive and Child Health II/National Rural Health Mission (RCH II/NRHM) period saw many substantial shifts, which drove notable advancements for key indicators. Perhaps most important, the government launched a substantial effort to progress beyond home births supervised by traditional birth attendants and instead prioritized institutional delivery supported by skilled birth attendants.

In tandem with efforts to strengthen the capacity of the health system, the RCH II/NRHM period included many programmatic efforts to increase uptake of health services. These often operated through removal of financial barriers, active community engagement, and improved upgrades to health infrastructure. Several specific aspects of the RCH II/NRHM period are described in further detail as follows.

Upgraded health infrastructure

The RCH II period saw the establishment of the Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS), which set specifications and norms for all health facilities, including requirements that equipment must be ready in each room. These standards have been periodically updated since their inception, including a major update in 2012, with one government official saying:

“Bringing IPHS [Indian Public Health Standards] helped the states in getting a vision that you have to achieve up to these standards. The standards helped, and the various guidelines also helped the states in achieving the standards and quality.”

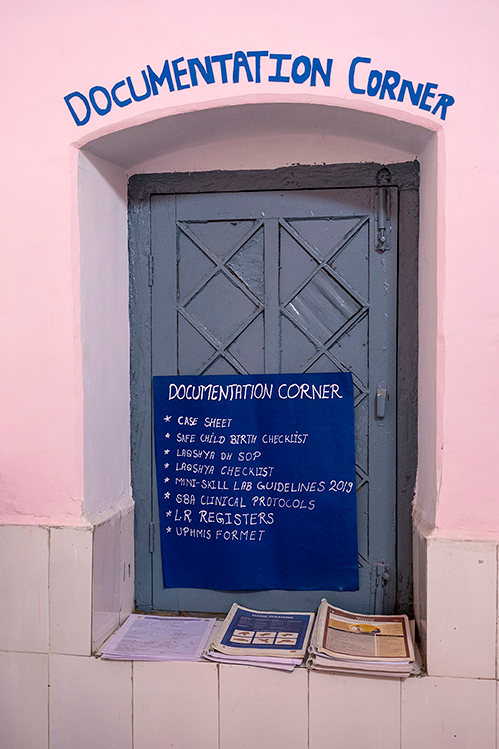

The creation of other regulatory bodies, such as the National Accreditation Board for Hospitals and Healthcare Providers, helped promote the maintenance of well-equipped facilities across the country. These operated in tandem with more local efforts such as facility committees and patient welfare committees. More recent efforts include the 2017 Labour Room Quality Assurance Initiative (LaQshya), which emphasized the importance of patient-centered maternity care in its quality standards. One development partner noted the implications of these efforts on improved facility quality over time:

“From the years 2010-2012 onwards until now where there has been this intended, intentional transition from being focused on or even just monitoring access […] to get into quality of services. Both at facilities and outreach […] So, so that shift from numbers to quality of care approach or paradigm.”

Coordinating and upskilling human resources for health

Beginning in the RCH II/NRHM period, the government allowed contractual hiring of health care providers. Using a streamlined contractual process, states could hire additional workers and develop innovative strategies to attract health workers to fill vacancies that had historically been difficult to keep staffed. These innovations included allowances and increased pay for vacancies in isolated areas, preferential selection to post-graduate positions for providers who worked in rural areas, and mandatory service in rural areas for new graduates. These strategies were highly variable across the country, as one government official described:

“States came up with all kinds of options based on the local conditions. I think in 2009 or 2010 we made a list of all of the possible innovations that different states were trying. But those innovations were at preliminary stages. But, I think we came up with something like a hundred of them. Different guys trying out different things. And although, not too many of them really got scaled up and some did like the special transport business, but nevertheless, I think it had a big impact on the human resource.”

The government also undertook innovative training approaches to strengthen the country’s existing health workforce. Auxiliary nurse midwives and staff nurses, and later, providers of Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy (AYUSH)—the six forms of nonallopathic medicine practiced in India—were offered pathways to becoming licensed skilled birth attendants. This program included a 21-day training course as well as seven days of hands-on practice.

These broader training pathways were complemented by task-shifting initiatives targeted to known, common issues in the maternal care pathway. For example, in 2014, an update to the home-based newborn care guidelines permitted auxiliary nurse midwives to provide a full seven-day course of antibiotics for neonatal sepsis to families that did not accept being referred to facilities—which would have previously not been permissible. One civil society member interviewed spoke to the impact of these trainings, saying:

“Not many people may talk about it or even understand the enormity of it, but I think under the SBA [skilled birth attendant] initiative when tasks were shifted and the government allowed and trained auxiliary nurse midwives and staff nurses to do some of the skills, I think that was, that would have ended up in saving many, many lives.”

There were also pathways for general physicians to learn lifesaving anesthetic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care (CEmOC) skills to fill vacancies in the place of specialist providers. In an effort to empower providers to use their newly acquired skills, some states also offered legal protections from liability to generalist medical officers who had undergone this training in the case of maternal or newborn death.

Accredited social health activists (ASHAs)

The cadre of female community health workers, known as accredited social health activists (ASHAs), was formed in 2005 and quickly grew to become a crucial link between communities and the health system. An assessment of the first four years of the RCH II/NRHM period from 2005 to 2009 found that there were 697,000 trained ASHAs, and by the next assessment from 2009 to 2014, the number had grown to 890,000., Selected from the communities they served, and trained on a series of health modules, the intention is to have one ASHA per 1,000 people, though this ranges slightly in practice. The program was initially introduced in rural areas of 18 high-priority states and later expanded to rural areas throughout the country in 2009, ultimately being further expanded to underserved urban areas in 2014. ASHAs were eligible for an incentive system based on how many women they supported in accessing health facilities for care.

Core ASHA roles include identifying and tracking women, children under five, and married couples to encourage them to utilize health services and to counsel them on health, nutrition, immunization, and family planning. ASHAs also provide basic curative care for minor illnesses and, when necessary, home-based newborn care. In 2014, a revision of the home-based newborn care guidelines expanded the ASHA role to include postnatal home visits. Assessments of data from Indian Human Development Surveys indicated that 30% of rural women who gave birth between 2005 and 2012 received ASHA services, with increased contacts among women who were poorer, in rural areas, or of a marginalized caste status. The ASHA program evaluation in 2010–2011 showed that around two-thirds of women had received home visits from ASHAs in sampled districts of eight states across India, with most women having been visited at least three times.

Contact with ASHAs is documented to have a positive effect on care-seeking, with an assessment from 2004 to 2012 finding that visits from ASHAs were associated with a 17% increase in any ANC coverage, a 5% increase in ANC4+ coverage, a 26% increase in SBA coverage, and a 28% increase in institutional delivery coverage. ASHAs also commonly accompany mothers to facilities. A recent study in Uttar Pradesh found that 92% of women who had an institutional delivery were accompanied during their travels, with the ASHA staying with them at the facility in 61% of cases.

Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) cash incentive program

ASHAs were crucial in the implementation of the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) cash incentive scheme, launched in 2005. As part of this program, all women in “low-performing states” were eligible for cash incentives if they delivered in public facilities or accredited private facilities. Additionally, women living below the poverty line or belonging to marginalized castes in high-performing states were also eligible. Incentives started at 700 Indian rupee and increased in 2013 to 1,400 rupee in rural areas and 1,000 rupee in urban areas.

ASHAs were also given 600 rupee as an incentive for each delivery they supported in reaching a public facility for delivery. One assessment in Uttar Pradesh highlighted the role ASHAs played in driving the JSY program’s success, finding that 72% of women who delivered in facilities learned about the JSY program from an ASHA. In one year after inception, the number of JSY beneficiaries grew from 740,000 to 3.16 million, ultimately reaching about 11 million recipients by 2017–2018., The impact of this program was highlighted by several interviewees, including one civil society member who said:

“JSY was a really kind of flagship program because at that point in time it was really, really important to increase coverage of essential maternal health services. And a primary way to do that was to get women to come to hospitals. […] So I think this trend of getting women to point-of-care started with JSY.”

Although the program covered deliveries at both private and public facilities, the majority of covered births took place in public facilities, especially CHCs and PHCs. By the end of the RCH II/NRHM period in 2012, almost 90% of deliveries in “low-performing states” reported receiving JSY cash incentives, whereas only 27% reported receiving incentives in high-performing states, primarily due to differences in eligibility criteria. The RCH II/NRHM period saw a substantial narrowing in the institutional delivery gap between higher and lower mortality state clusters, and evidence suggests that the success of the JSY program was a key contributing factor.,

Budgetary flexibility

To accompany the JSY program, the government revised funding approaches to ensure that incentive payments would not be disrupted by existing regulations. One government official described states’ health expenditures as “strait-jacketed” by restrictive accountability norms before the RCH II/NRHM period. This was alleviated by the creation of “flexi pools,” which allowed the states to fund initiatives—such as JSY payments—from a pool rather than a tight line item. This ensured that outgoing JSY payments could continue uninterrupted from the flexi pool in case the budgeted amount was insufficient, with the flexi pool replenished later as informed by the state’s financial reports. As another government official said:

“With RCH I there was no flexibility at all.[…] But in the RCH II they basically said, ‘Look, there are wide variations across states, you have unique state level and district level problems, so while certain things maybe like JSY how much money should be given to a woman, but we’ll also give you a certain percentage of this money as flexible so you can use that either for innovations or for plugging in gaps. It’s really up to you.’ This, I think made a big difference.”

Village Health and Nutrition Days

Another key community engagement strategy in India was the Village Health and Nutrition Days (VHNDs), which the government established guidelines for in 2007 during the RCH II/NRHM period. VHNDs are monthly outreach events, usually on Wednesdays, that feature an auxiliary nurse midwife from a local HSC or PHC. At this event, an auxiliary nurse midwife conducts check-ups, antenatal care visits, immunizations, and education modules. Before the VHND, local ASHAs encourage women and children to attend, and they support the auxiliary nurse midwife during the event. These events are also supported by Anganwadi workers who provide nutrition services and local elected leaders who ensure the event takes place in an appropriate location.

VHNDs are an important mechanism for interacting with remote, rural, and poor populations who may be difficult for the health system to reach. Among these communities, one of the central goals of VHNDs is to integrate essential basic services into outreach efforts. In particular, the VHND has been linked to improved ANC coverage, as the percentage of women who received their ANC at a VHND or other village level center increased from 7% to 27% between 2001 and 2018., This trend is even stronger in the higher mortality state cluster, which saw an increase from 10% to 39% during the same time period.,

“108” ambulatory services

While the previous RCH I period included several pilot programs that aimed to provide ambulatory services, none proved scalable. However, the “108” ambulance service—named after the toll-free phone number by which the service can be reached—was adopted by the Indian government during the RCH II/NRHM period. In many states, this initiative has relied on strong private–public partnerships that have helped it become successful.

Upon dialing the 108 number, a patient’s location can be assessed relative to the position of nearby ambulances that are digitally tracked using a GPS system. Workers in a call center then dispatch an ambulance to the appropriate site, with free transport provided for all deliveries, neonatal illnesses, or interfacility transfers in cases of complication. Data from the end of the RCH II/NRHM period in five states (Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, and Himachal Pradesh) indicates that 20% to 25% of all institutional deliveries were transported using the 108 ambulance service and that women who were poorer or lived in rural areas were more likely to use the service. One government partner noted the effect of this program not only on initial transport, but also on referrals in case of complications, saying:

“Referral transport was scaled up across the states in a big way. And I think that helped in terms of very fast, shifting of bleeding or an eclamptic woman. So, right from the village or PHC [primary health center] levels, straight away a woman could be taken to a medical college or district hospital.”

Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakaram program

Near the end of the RCH II/NRHM period, the Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakaram (JSSK) program was established, aiming to eliminate out-of-pocket costs for delivery and newborn care. This initiative covered normal delivery costs, C-section costs, drugs required for delivery, blood transfusion services, food, transportation to health facilities, and transportation from health facilities to home as appropriate. Removing financial barriers to care was especially timely for newborn care considering that in 2008, Special Newborn Care Units were sanctioned in all district hospitals, but they were originally not as accessible for rural or poorer populations. One government official called JSSK “a step in the direction of universal health care,” while a civil society member spoke to its overall impact by saying:

“JSSK was a very thoughtful gesture, kind of recognizing the out-of-pocket expenditure on transport and food, etc., and you know, ensuring that at least that got covered. And that did work, it actually did work. Because wherever you have money tied, or budgets tied to a scheme, it does actually get monitored. You know, because there’s money.”

In practice, there is evidence that JSSK does not eliminate out-of-pocket costs completely but has been found to reduce financial barriers to delivery and neonatal care. There is substantial variation across states in terms of typical financial barriers still faced, necessitating continued and tailored streamlining of JSSK as it seeks to address the complete spectrum of costs that are faced in delivery and newborn care.,

Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (and Adolescents)/National Health Mission (2012–2020)

Following the RCH II/NRHM period, the Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child (and Adolescents)/National Health Mission (RMNCH+A/NHM) sought to build on momentum, with some adaptations as India evolved.

There was a notable shift to consider the life-course of a mother and baby dyad, reflected by an increased focus on adolescent health and maternal nutrition during this period. For example, this period saw the expansion of a maternity benefit program called the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY), which provided cash incentives for first-time mothers who followed best practices for safe delivery, maternal nutrition, and breastfeeding in high-burden districts. Additionally, in 2014 JSSK was expanded to cover a broader time horizon beyond delivery care itself, including antenatal care and postnatal care.

With the RCH II/NRHM period making strides on improving coverage across the country—and narrowing coverage gaps between higher and lower mortality state clusters—the RMNCH+A/NHM period also included a shift toward prioritizing quality of care. Norms for facilities were reiterated and expanded upon through the establishment of the 2013 National Quality Assurance Standards that delineated expectations of care in health facilities,, the 2017 Labor Room Quality Assurance Initiative (LaQshya) that prioritized patient-centered maternity care, and the 2020 Surakshit Matritva Aashwasan that outlined maternal health rights when accessing health care.

Another facet of improving quality of care was revitalizing the workforce through a series of additional training programs. The Daksh and Dakshata skills labs, respectively established in 2014 and 2015, that aimed to enhance clinical competency of auxiliary nurse midwives, staff nurses, and medical officers across government facilities, especially in aspects of basic emergency obstetric and newborn care (BEmONC).,

This prioritization of quality throughout the RMNCH+A/NHM period was marked by leadership that sought to address issues instead of masking them. One interviewed government official spoke to this, specifically with regard to how providers were assessed against standards and throughout trainings, saying:

“Monitoring earlier was a sort of inspection. And when it is inspection people they try to hide their fault and try to show you that everything is good. And then the scope of improvement is less. So instead of monitoring, we started calling it supportive supervision and there is an RMNCH+A guideline on the supportive supervision, where we’ve focused on the fact that you go there, not for the fault finding, you go there to support the staff. If you see and observe any gaps you don’t start chiding them. You try to solve it.”