Key Points

Senegal has implemented a diverse set of community health cadres that provide preventative, curative, and referral-based services to vulnerable populations, connecting them to the public health system.

Longstanding political commitment to nutrition coalesced in 2001 into a key operating body, the CLM, which served as the driver of nutrition programming from the 2000s until present day. The CLM championed and implemented a key nutrition program, the PRN.

Through the Water Sector Project and subsequent water- and sanitation-related programming, Senegal increased access to key WASH services, primarily to urban areas at first. The country has more recently been searching for productive ways to serve rural areas as well.

The government expanded access to education, increasing the percent of children attending school, especially girls. One probable knock-on effect of higher enrollment, besides remarkable improvements to literacy, was women delaying pregnancy and having fewer children.

Maternal and newborn care

Senegal’s Cases de Santé, or health huts, have been providing basic treatment for common diseases since the 1950s. Health huts are the backbone of Senegal’s community health system, and they deserve much credit for Senegal’s impressive progress on disease prevention and treatment, including its far-reaching immunization program, climbing rates of oral rehydration therapy for diarrhea, improvements in maternal health, and plummeting malaria incidence and mortality.

Community health providers cadres

There are now five major cadres of community health workers: ASCs, matrons, DSDOMs, relais and bajenu gox.

TIMELINE: | 1950s–present |

The expansion of the health system through Cases de Santé, to reach rural and vulnerable communities, was critical to the reduction of stunting rates. In fact, in our analysis, . This improvement reflects the efforts of Senegal’s community health workers to provide care for mothers and children, especially in rural areas out of reach of the formal health system.

Key indicators demonstrate the results of these efforts. The proportion of mothers who made the recommended number of prenatal visits (four or more) more than tripled during the study period, increasing from 14 percent in 1993 to 57 percent in 2017, In rural areas, attendance at birth by a skilled health provider almost doubled during the same period, from 29 to 56 percent, Nationwide coverage of the Diphtheria, Pertussis, and Tetanus (DPT) vaccine, an indicator of the strength of the immunization system as a whole, rose from 51 percent to 93 percent, These changes, especially pronounced in rural areas, reflect the impact of the community health system.

This data suggests not only that mothers and babies were receiving health care at key moments but also that they were in touch with the health system throughout the critical first 1,000 days. As a result, they were more likely to receive messages about important behaviors like infant and young child feeding. We can see that expressed in the data, for example, with the rate of exclusive breastfeeding improving from just 5 percent in 1992 to 42 percent in 2017.

One of the remarkable things about Senegal’s community health system is that it is much larger than the formal health system and still growing. This is both a reflection of Senegal’s goal of decentralization and a reaction to the scarcity of doctors and nurses in the country, especially in rural areas.

While the WHO recommends a minimum of 2.3 formally trained health workers per 1,000 population, Senegal has just 0.38 as of 2016 (fewer than 6,000 nationwide). These physicians and nurses are concentrated in Dakar and other urban areas, and work primarily in the country’s 1,200 government-run and 500 private health facilities. In contrast, as of 2014, there were more than 16,000 health workers within the community system working in approximately 2,300 health huts. These community health workers serve Senegal’s rural areas, where the national shortage of doctors and nurses is most acute.

Additional Reading:

Nutrition commitment

The beginnings of nutrition policy and program reform date back to 1995. Before this, the Ministry of Health had housed Senegal’s nutrition efforts, but nutrition was simply not a priority when it came to budgets, human resources, and programming.

In the wake of the currency devaluation-and partially in response to the unrest it caused-the World Bank approached the Agence d’Execution de Travaux d’Intérêt Publique (Executing Agency for Public Works and Employment; AGETIP), a private nonprofit, to implement the World-Bank funded Projet de Nutrition Communautaire (Community Nutrition Program; PNC), which ran through 2001. The Bank conditioned financing for the project on the creation of a high-level oversight organization. The head of AGETIP, who had connections to President Abdou Diouf, persuaded the president to set up the Commission Nationale de Lutte contre la Malnutrition (National Committee for the Fight Against Malnutrition; CNLM) not in the Ministry of Health but in the President’s own office.

While the CNLM and the PNC laid the groundwork for the robust nutrition-related policies and programs that characterize Senegal today, neither was considered a major success on its own. Among other issues, the CNLM offered no incentives for participation and failed to define clear roles and responsibilities for key stakeholders.

The PNC, meanwhile, turned out to be as much an employment program as a nutrition program. This made some sense, given that it was administered by an employment agency and designed to ease suffering after the currency devaluation.

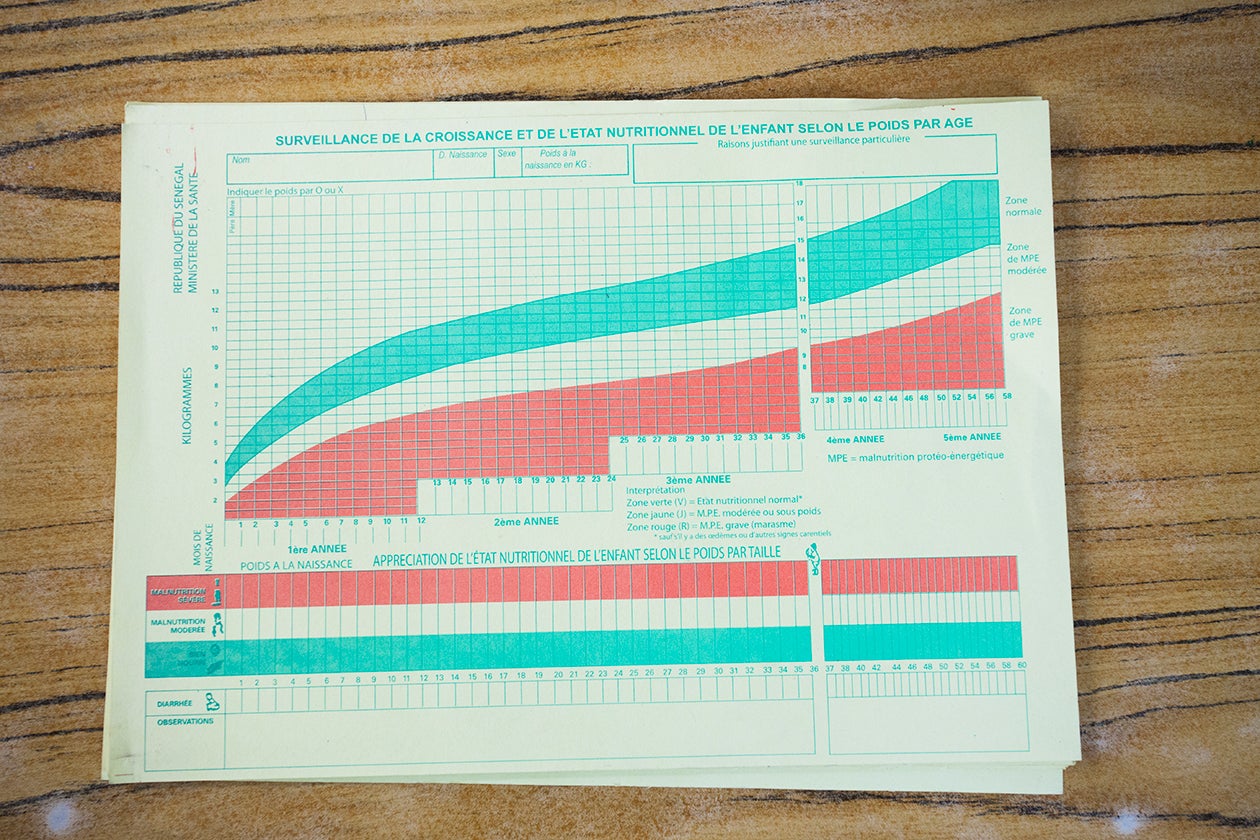

The program hired four unemployed youth in each target area to staff nutrition centers and trained them to deliver a range of nutrition interventions, including growth monitoring, nutrition education and promotion, referrals and follow-up for cases of severe acute malnutrition, and the distribution of local foods. In practice, however, the main intervention turned out to be food distribution, which was popular, but expensive and less effective than other interventions that were neglected, such as education and growth monitoring. In addition, since the program’s goal was to quell urban unrest, it targeted cities, even though the highest burden of malnutrition was in rural areas.

Despite these challenges, however, the CNLM and PNC together demonstrated that Senegal had both the political will at the highest levels and the multi-sectoral outlook to tackle nutrition in earnest. They also provided valuable lessons that would inform the design of later programs.

Additional Reading:

Cellule de Lutte Contre la Malnutrition / Coordination Unit for the Fight Against Malnutrition (CLM)

Coordinating body for nutrition in Senegal, housed within the Prime Minister’s Office.

TIMELINE: | 2001-Present |

Programme de Renforcement de Nutrition / Nutrition Enhancement Program (PRN)

Program aimed at improving the nutritional status of children through community-level interventions and strengthening the country’s institutional and organizational capacity for the implementation and evaluation of nutrition policy.

TIMELINE: | 2002-2006 (reformed into the PRN II, 2007-2014) |

FUNDING: | $23M (PRN I) |

COVERAGE: | 35% of target rural population, 50% of target urban population (PRN I) |

In 2000, Abdoulaye Wade was elected president, and, along with his wife, he made nutrition a priority. In 2001, he oversaw a series of important changes to policy. His government issued a new policy brief on nutrition, the Lettre de politique de développement de la nutrition (Nutrition Development Policy Letter; LPDN), which aligned the country’s nutrition-related commitments to the Millennium Development Goals. The LPDN highlighted Senegal’s evolving understanding of the multi-factorial causes of stunting and focused on nutrition, health, and sanitation. Under President Wade, nutrition was also given its own line in the national budget for the first time. Finally, Wade replaced the CNLM with the more effective Cellule de Lutte Contre la Malnutrition (Coordination Unit for the Fight Against Malnutrition; CLM), located in the prime minister’s office. Importantly, he created an implementing arm for the organization, which meant that whereas CNLM has only provided oversight and AGETIP administered PNC, the CLM itself would administer future nutrition programs.

In 2002, the CLM and the World Bank launched the Programme de Renforcement de Nutrition (Nutrition Enhancement Program; PRN), which built on the lessons learned from the PNC experience. The PRN was designed in a series of workshops that included members from all nutrition-related industries, the Ministry of Finance, donors, and NGOs. Bringing all stakeholders to the table from the beginning helped ensure that the program would be based on the best available global evidence. It also generated buy-in from numerous ministries, as did the fact that they were given incentives to participate, specifically in the form of training, equipment, and technical support.

The PRN contracted with local NGOs to deliver community-based nutrition interventions through health huts and other existing infrastructure. The NGOs hired and trained nutrition agents, who focused on growth monitoring, nutrition education and promotion, and disease prevention and treatment. These nutrition agents, backed by NGOs, worked across sectors, referring children suffering from severe acute malnutrition to public health facilities and working with schools to deliver nutrition curricula and distribute deworming tablets and micronutrient supplementation. It is difficult to determine coverage rates for the various interventions included in the PRN, but the program has established approximately 5,000 nutrition workers delivering services across the country.

The CLM and PRN are both considered significant successes, and Senegal’s nutrition policies and programming are generally praised by experts in the field. Since 2002, Senegal’s spending on nutrition has increased from $0.3 million to $5.7 million per year, although this figure does not include the money ministries spend on nutrition-sensitive activities. Incorporating nutrition-sensitive activities and external funding, the total spending on nutrition in Senegal between 2012 and 2015 was $195 million, or approximately $49 million a year. Almost 90 percent of that was contributed by external donors).

Still, the impact of these policies, programs, and spending on stunting is debated. Based on the Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates, developed by the World Bank Group, WHO, and UNICEF, suggests that most of Senegal’s stunting decline occurred before the scale-up of the PRN I (2002-2006). This conclusion is based on the exclusion of two data points:

- The 2010-11 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) datapoint (26.6 percent under-five stunting prevalence) because after review of the underlying data, 24 percent of the anthropometric data is implausible or completely missing.

- The 2012 SMART datapoint (15.5 percent under-five stunted) given it is a non-standard survey and there is an alternative 2012-2013 DHS datapoint (18.7 percent) to use that is methodologically consistent.

If we were to include the 2012 SMART survey figure, the stunting rate can be interpreted as continuing to fall through the late 2000s and early 2010s.

Despite this uncertainty, Senegal now has some of the most sophisticated nutrition policies and programs on the African continent, and through the CLM, all relevant ministries are engaged in thinking about addressing malnutrition (not just stunting but also other challenges such as underweight and wasting).

Additional Reading:

Water and sanitation

Starting in the mid-1990s, Senegal partnered with the World Bank to spearhead a major reform of its water and sanitation sectors. The underlying principle of these reforms, which are ongoing, is privatization. The government contracted with private companies to provide water and sanitation services to the Senegalese population. With user fees, these private companies were able to vastly improve the quality of services while promoting equity by subsidizing water and sewer connections for those who could not afford to pay.

Water Sector Project

Program focused on improving water and sanitation coverage through privatization of the water supply.

TIMELINE: | 1996-2004 |

FUNDING: | $290M (upfront investment) |

COVERAGE: | 1 million estimated served (primarily in urban areas); note: project was dedicated to improving quality of underlying infrastructure, not just coverage |

In 1996, the Bank launched the Water Sector Project, which focused specifically on the urban water sector. The project replaced the state-owned water utility with a state holding company that owns all of Senegal’s water-related assets, as well as a private operating company that leases those assets and runs the system. Alongside these changes, the project also created a public sanitation company that would eventually lead reforms in the sanitation sector.

The private operating company, Sénégalaise des Eaux (Senegalese Water; SDE), gradually increased the annual water tariff to cover its costs while also increasing quality of the service. At the same time, the government created a national fund to subsidize poor people’s connections to the system. Ultimately, the Water Sector Project extended water supply services to approximately 1 million people. According to the Bank, the project “is regarded as a model of public-private partnership in Sub-Saharan Africa.”

Progress in the rural sector was slower. In 1999, the Reform of the Management of Rural Boreholes (REGEFOR) Project sought to privatize the management of boreholes in the same way the Water Sector Project had privatized the management of urban water systems, but it struggled because the local users’ associations had neither the technical capacity to manage the systems nor the money to maintain them.

In 2005, the World Bank and other donors assisted in the launch of the Programme d’Eau Potable et d’Assainissement du Millénaire (National Millennium Water and Sanitation Program; PEPAM), which aimed to build on the lessons of the Water Sector Project and REGEFOR. Senegal created a national-level holding company to replace the small, community-level rural users’ associations. Meanwhile, rural private water system operators were given more leeway. By 2013, 6.3 million of 7.5 million rural residents had access to safe water from boreholes, hand pumps, or modern wells . The privatization approach has scaled up access to water, but it is possible that, despite the fact that the program subsidized connections for some of the poor, water tariffs have exacerbated inequity for the poorest.

Progress in the sanitation sector lagged behind progress in the water sector; not until PEPAM, in 2005, did real improvement efforts start. These efforts have been more successful in cities than in rural areas, though progress has been made everywhere. People in urban areas responded well to campaigns promoting subsidized connections to the sewerage system. In peri-urban areas, meanwhile, where sewer systems were not affordable, the focus shifted to on-site sanitation and small-bore sewers, accompanied by subsidies and an awareness-raising campaign. Between 2002 and 2008, these programs benefited 500,000 people, or 25 percent of the peri-urban population of Dakar, and as of 2011, the approach was being replicated in five other cities with funding from the EU.

Rural sanitation has been much slower to improve because, despite awareness-raising and subsidy programs, high technical standards, inflation, and the difficulty of getting building materials from Dakar make toilet construction projects prohibitively expensive. More recently, Senegalese communities have adopted Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS), an NGO-led behavior-change methodology for eliminating open defecation that focuses not on building toilet facilities but rather on generating demand for safe sanitation within communities. CLTS has driven sizable declines in open defecation in other countries, particularly in South Asia, where the methodology originated.

According to our decomposition analysis, improved access to piped water accounts for 8 percent of the change in HAZ. Indeed, key indicators across the area of sanitation and hygiene improved significantly during our study period. Between 1992 and 2017, access to an improved source of drinking water rose from 52 percent to 81 percent, piped water from 47 percent to 74 percent, and improved sanitation from 22 percent to 51 percent. Meanwhile, households using no toilet facility fell from 40 percent to 13 percent.

Notably, improvements in water and sanitation typically address the burden of diseases like diarrhea and pneumonia that stunt children’s growth. In Senegal, however, the data does not line up as we would expect.While the incidence of pneumonia decreased significantly, the incidence of diarrhea was basically flat, dropping from 20 percent to 18 percent between 1992 and 2017. One possible explanation is that while the incidence did not decrease significantly, the severity of cases did.

Additional Reading:

Education

Senegal has played a leading role in global discussions on improving access to, and improving the quality of, education. In 2000, Senegal hosted the second World Conference on Education for All in Dakar. The participants adopted what they called the Dakar Framework, including six specific education sub-goals that supported the larger Education for All goal: to meet the learning needs of all people by 2015.

Programme Décennal d'Éducation et de Formation (Ten-Year Education and Training Program; PDEF)

National program with the objective of educational reform. Priorities included increased access to universal quality education, supporting vulnerable populations and improving literacy and training of adults.

TIMELINE: | 2000-2010 |

KEY STAKEHOLDERS: | Ministry of Education, World Bank, Canadian International Development Agency, Agence Francaise de Developpement (French Development Agency; AFD) |

Plan National d’Actions de l’Education Pour Tous (National Action Plan for Education for All)

Policy integrated into the PDEF to reinforce the commitment to educational reform and pilot key interventions that were identified (e.g. improvement of teaching programs)

TIMELINE: | 2000-2015 |

EXAMPLE SUB-SECTOR FOCUS AREAS: | Example sub-sector focus areas: Development of science and technology education, improved girls’ primary education, integrated early childhood development, etc.) |

Following the conference, Senegal launched a flurry of education policies and investments, including the National Action Plan for Education for All and the Ten-Year Education and Training Plan, both of which were structured according to the Dakar Framework. In 2001, Senegal’s new constitution guaranteed that “all children, boys and girls, throughout the national territory, shall have the right to attend school.”

Goals of Education for All:

1. Expanding and improving comprehensive early childhood care and education, especially for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged children; | 4. Achieving a 50 per cent improvement in levels of adult literacy by 2015, especially for women, and equitable access to basic and continuing education for all adults; |

2. Ensuring that by 2015 all children, particularly girls, children in difficult circumstances and those belonging to ethnic minorities, have access to a complete free and compulsory primary education of good quality; | 5. Eliminating gender disparities in primary and secondary education by 2005, and achieving gender equality in education by 2015, with a focus on ensuring girls’ full and equal access to and achievement in basic education of good quality; |

3. Ensuring that the learning needs of all young people and adults are met through equitable access to appropriate learning and life skills programmes; | 6. Improving all aspects of the quality of education, and ensuring excellence of all so that recognized and measurable learning outcomes are achieved by all, especially in literacy, numeracy, and essential life skills. |

We only have data going back to 1998 on education spending; since then, Senegal’s investments in education have exceeded 15 percent of the national budget-and exceeded its investments in health care. While it is extremely difficult to track how that money is actually spent, we can see improvements in enrollment over the following years.

Between 1992 and 2017, primary school enrollment increased from 44 percent to 72 percent, and the gender parity index increased from 0.74 to 1.12. In other words, in 1992 there were three girls for every four boys in primary school, but by 2017 there were more girls than boys.

This increased enrollment translated into a remarkable shift in literacy - especially among girls. In 1988, the overall literacy rate among Senegalese 15 and older was 27 percent. By 2016, it had almost doubled to 52 percent. In 2017, just 7 percent of women 65 and over could read, whereas 64 percent of girls 15-24 were literate. Still, one third of girls today cannot read, and improving literacy rates further would probably help accelerate the stunting reduction.

There are several different pathways by which education might lead to reductions in stunting.

Better-educated mothers and fathers tend to earn more and know more about health and nutrition, which gives them more resources to devote to their children and a better understanding of how to do so. In addition, educated mothers are more likely to be empowered to make decisions more conducive to children’s health, and educated fathers are more likely to accept women in decision-making roles. Finally, merely educating girls (future mothers) has an important impact. The longer a girl stays in school, the longer she delays motherhood. That delay, in and of itself, is important for reducing stunting. Biologically, older mothers are healthier, stronger, and more prepared for the rigors of pregnancy and childbirth, which means their children tend to be healthier, stronger, and taller. But delays also reduce the number of children a woman will have in her lifetime, another important lever for reducing stunting, as parents with fewer children can spend more resources on each child.

Additional Reading:

In Senegal, data indicates women are indeed having fewer children, and having them later in life. The median age at first marriage for women aged 20-49 rose from 16.6 years in 1992 to 19.7 years in 2015. Meanwhile, the adolescent fertility rate declined from 127 per 1,000 in 1992 to 78 per 1,000 in 2017, and the total fertility rate dropped from 6 in 1992 to 4.6 in 2017 . Although increases in girls’ secondary school enrollment may have played a role in these changes, that enrollment rate is still very low, at 37 percent, so it seems unlikely that girls’ education was the only factor contributing to delayed marriage and childbearing and smaller families.