While each of the Exemplar nations operated within their own distinctive political, economic, cultural, and geographic contexts, findings from the research revealed striking similarities in their successful efforts to reduce U5M.

This section describes five recommended cross-cutting strategies commonly adopted by Exemplar countries. Regardless of specific national circumstances, Exemplar countries prioritized these five strategies while implementing interventions to reduce U5M. The strategies hold value for other countries looking to implement evidence-based health interventions or to address gaps in implementation of existing interventions.

Details and examples of each recommended strategy are presented in a table at the end of each section.

1) Stakeholder Engagement and Coordination:

Seeking input early and often from local and international partners and donors, in order to establish buy-in, facilitate adoption, ensure feasibility, and drive coordinated implementation around a national plan.

Ministries of Health in Exemplar countries engaged donors and partners (both international and national) early in the process of introducing new EBIs, and continued to leverage the expertise and resources of these groups throughout implementation.

This involvement was crucial to EBI implementation and success, though it was dependent on strong donor and partner coordination, and on keeping donor and partner priorities in line with the national vision and goals.

Typically, a ministry of health (MOH) would convene NGOs, donors, multilateral agencies, and other partners in technical working groups. These groups relied upon the expertise of local academics, research institutions, and professional societies, increasing the capacity for local research and trainings throughout the process.

The working groups decided the appropriateness of a new EBI or adaptation, and planned for its introduction. In Peru, for example, the Neonatal Health Collective pooled resources and expertise to generate health standards and develop epidemiological surveillance programs.

Exemplar countries also convened gatherings of officials and experts from across sectors. By bringing together leaders in education, sanitation, finance, and other areas relevant to public health, governments could coordinate and facilitate a range of U5M interventions. These meetings between the government and other stakeholders were often combined, to ensure an intersectoral approach in line with the national vision and priorities established by the MoH.

Countries used specific strategies to regulate and coordinate with partners and donors, retaining control over where and how projects would be implemented. In Rwanda, for example, officials rejected would-be partners and donors who would not work within the government’s requirements.

Read More: Detailed Steps and Additional Country Examples

2. Use of Data and Evidence for Decision-making

Drawing upon international, national, and sub-national data and evidence for planning, implementation, and advocacy.

Exemplar countries invested in national data systems, and in the capacity needed to manage and utilize that data. They also fostered a culture of data use, aggressively opening up channels to gather and interpret locally generated data. This created ongoing feedback loops for learning and accountability throughout the EPIAS implementation process. For example, Rwanda developed a culture of data use by investing in capacity and skills for data use and awareness at both the central and district level and empowering health officials at all levels of government to use data for decision-making. Rwanda invoked a pre-colonial concept of imihigo (meaning "to vow to deliver") and created performance contracts between the districts and national government including indicators and targets which the districts were held responsible for meeting.

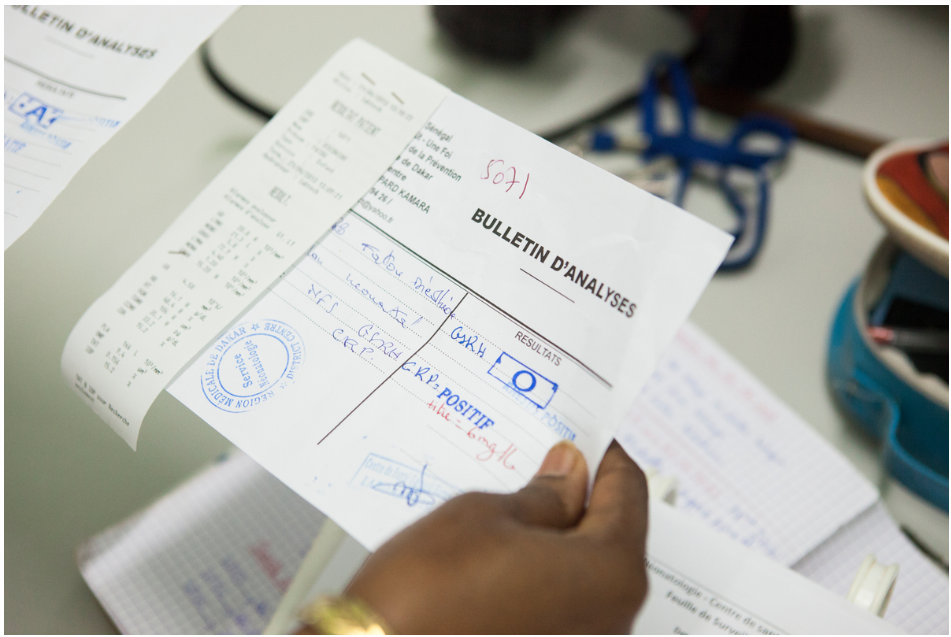

Officials used multiple data sources, such as Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), Health Management Information Systems (HMIS), and international estimates of burden of disease. Senegal, for example, drew simultaneously upon epidemiological, entomological, meteorological and environmental data sources to inform delivery of intermittent preventive treatment (IPT) for malaria.

In addition to data usage, strengthening data systems was another key success factor for Exemplars. For example, Senegal built out a strong surveillance system, which they used to monitor the effects of ACT and RDT introduction for malaria. In addition, they introduced an electronic health information system in 2005 to capture and report on facility-level data and began conducting the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) every year after 2011 (compared to an average of every five years in other countries). Exemplars placed a high priority on gathering information from the hardest-to-reach and poorest communities, and on identifying the regions that were in most urgent need of a particular vaccine or other intervention. In many cases, governments put high-need areas at the top of the list for piloting and early rollouts to ensure implementation plans were designed to serve the communities with greatest need and to target those areas first.

The EBIs that were the focus of this research all had credible global evidence on effectiveness. This enabled some countries to swiftly introduce EBIs, without first undergoing pilot studies or other time-consuming local research (for example with PCV rollout in Rwanda). However, other Exemplar nations built upon national or global data with effective use of small-scale pilots, to help understand local contexts and inform strategies to ensure the feasibility and sustainment of EBIs.

Data also figured prominently in the adaptation stage, when ongoing monitoring data – particularly at a sub-national level – could identify areas where additional resources or adaptations were required in order to achieve targeted coverage levels.

In addition, disease-specific and sentinel surveillance systems were critical for responding to outbreaks and targeting interventions, such as for measles and malaria. These systems also proved useful in revealing persistent gaps in coverage.

Read More: Detailed Steps and Additional Country Examples

3. Integration of new and existing initiatives into health systems

Building upon and strengthening effective health-care systems, including CHW networks.

A key element of the Exemplar countries’ success was their ability to integrate new interventions and initiatives into existing health systems. Through this integration, the Exemplars strengthened the overall health system, while simultaneously reducing risk of duplicative work, resource wastage, and shortfalls in capacity.

A focus on integration was often coupled with strengthening overall health systems to support introduction of new interventions. Across Exemplar countries there was a shift from vertical to integrated horizontal programs – in other words, from systems designed to deliver single-disease interventions to integrated primary care that could better provide the range of services needed to reduce U5M. The adoption of IMCI (Integrated Management of Childhood Illness) exemplified and accelerated this transition, often combining what had previously been vertical interventions for malaria, respiratory infections and diarrhea. For example, in Peru, vertical ARI and diarrhea programs were integrated into IMCI as part of the 2003 Comprehensive Childhood Health Care Model.

Another example is in Rwanda, where the government shifted from externally-funded, vertical HIV programs to an integrated program within existing primary health care systems. As part of this, they funded development of delivery rooms, labs, and cold chain systems that were used for both HIV treatment and primary care. In addition to these synergies for the primary care systems, this integration enabled better monitoring of the HIV programs under the Rwandan government’s national priorities.

Many Exemplar countries integrated interventions and programs into community health worker (CHW) programs. One example of this was Ethiopia’s integration of IMCI into its highly successful Health Extension Worker program.

In fact, the presence of vibrant CHW programs – most of which were already in existence when the study period began – was a clear common denominator among all Exemplar countries.

The CHWs worked predominantly in rural areas, often in the same communities where they had lived and grown up. Much of their success derived from the high level of trust that community members placed in them.

But this trust was only one of the factors contributing to the impressive performance of CHW systems. Those systems also relied on mechanisms for accountability; ongoing communication between CHWs and the communities; and a strong connection to primary-care facilities for CHW training and supervision. For more information on best practices in CHW programming, please see the Exemplars in Community Health Workers Cross-Country Synthesis.

The robust CHW systems in these countries made it possible to address gaps in coverage – especially in rural and hard-to-reach areas – by making health services more accessible to communities that previously had low access to care. This responsiveness was essential to the reduction of U5M.

Exemplars strengthened their health systems in other ways to support integration too. They did so by increasing the number of health workers, but just as importantly by developing the skills of their health workers. This began with training and education, both pre-service and in-service training. For example, in Peru, the government introduced new interventions by cascading knowledge from professionals at the regional level to health workers at the local level. In Ethiopia, the Ministry of Health worked with local universities to integrate new evidence-based interventions into pre-service training for healthcare workers in support of sustainability.

Beyond initial training, supportive supervision of the healthcare workers and systems able to support care delivery were critical to ensuring continuous improvement and quality of care. In Nepal, the Female Community Health Volunteers (FCHVs) had supervision meetings with health facility workers every six months.

Read More: Detailed Steps and Additional Country Examples

4. Building and Using Research Capacity

Bolstering in-country research organizations and capacity to inform decision-making and gain local buy-in.

In addition to strengthening routine data collection and use, Exemplar countries also built and strengthened institutions for in-country research to produce new knowledge needed for informed decision-making. This research capacity then played an integral part in the selection and adaptation of interventions and the strategies used to implement them.

To develop highly-qualified research personnel, some Exemplars embedded research talent within a ministry of health (MOH) or financed graduate degrees for MOH staff, as was the case in Rwanda. In other cases, academic or independent research organizations developed outside of the government, eventually developing sufficient capability and scale to serve as effective partners in national U5M-reduction efforts. This was the case with the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research (ICDDR,B) in Bangladesh or Cheikh Anta Diop University in Senegal.

Regardless of whether they emerge within or outside an MoH, the input of such research organizations could influence multiple stages of the decision-making process.

During the exploration and preparation phases, these research groups played a variety of roles, such as designing and implementing pilot studies to determine whether rapid or phased scale-up would be more effective under a given set of circumstances. Another critical role was the analysis of data on the burden of disease, including information on the localities that could be best served by an early rollout of a new intervention.

Beyond the exploration and preparation phases, research organizations in Exemplar countries helped with implementation and adaptation. Through pilot studies and program evaluations, they developed evidence to inform decision making. In addition, they used feasibility studies and capacity assessments to adjust global practices to local contexts.

Read More: Detailed Steps And Additional Country Examples

5. A focus on equity

Emphasizing the needs of the poorest and most vulnerable populations when developing health strategies.

The U5M Exemplar countries built policies around the understanding that under-five mortality is a reflection of inequities, both among nations and within them. Exemplars incorporated equity considerations into their policies from an early stage.

While it has not always resulted in eliminating child-health disparities, the emphasis on equity has often narrowed longstanding gaps between outcomes for the rich and the poor; urban and rural populations; and males and females.

Exemplar countries integrated an equity agenda into health-system strengthening efforts, program implementation, and governance decisions. In addition, contextual factors – including greater female empowerment; improvements in education; economic growth; and reduced fertility rates – also contributed to closing equity gaps.

Some countries achieved reductions in the U5M equity gap through efforts to increase coverage of interventions among targeted populations with the highest need. For example, equity considerations were employed when piloting an EBI to test feasibility before national implementation, to ensure the implementation approach was appropriate to the areas with highest need. Exemplar countries also conducted staged roll-out, with a priority on rolling out first in high-need areas, such as the IMCI rollout in Bangladesh.

Beyond health system interventions, Exemplar countries worked to narrow the gender gap in school enrollment between girls and boys. For example, Bangladesh provided girls with stipends for attending school at least 75% of the time and maintaining passing grades, as part of the Female Secondary School Stipend Project. In addition to education, Exemplars improved access to family planning to improve reproductive rights for women. This was done by integrating family planning into national priorities and by having community health workers promote family planning measures (as the Female Community Health Volunteers did in Nepal). These efforts indirectly contributed to U5M reductions and a narrowing of the equity gap.

Exemplar countries took a rights-based approach to ensure financial accessibility through systems designed to ensure equity. For example, as part of their community-based health insurance plan (Muteulle de Santé), Rwanda classified families in a village into socioeconomic categories. From here, they ensured access to healthcare for the poorest families by having insurance premiums and payments fully covered by the government or development partners.

Other Exemplars implemented programs to improve economic and health status more broadly, such as conditional cash transfers that required compliance with routine health services. Exemplar countries removed financial barriers to primary care services where possible, and some went as far as covering certain health-related costs, such as transportation. Despite these successes, some of these countries saw increases in out-of-pocket medical expenses, posing a challenge to equity now and in the future.