What is under-five mortality?

The under-five mortality (U5M) rate represents the risk of a child dying before reaching five years of age . It is expressed in terms of the number of children, out of 1,000 live births, dying before they turn five. The illnesses that cause these deaths are largely preventable, treatable, or both, and they are most common in low-resource settings.

Common causes of under-five mortality include acute respiratory infections, diarrhea, malaria, and birth complications. A number of underlying factors contribute to a child’s ability to fight off and recover from diseases. Malnutrition is the largest underlying driver of under-five mortality, making sick children more likely to succumb to otherwise non-lethal illnesses, and is estimated to underlie 45 percent of all child deaths.

When children die of these illnesses, it generally reflects multiple failures in the health system—failures in prevention and timely quality treatment. Addressing these challenges require evidence-based interventions (EBIs), combined with implementation strategies that ensure successful rollout and uptake among the population. In addition, successful implementation involves accounting for contextual factors, such as female empowerment, nutrition, and availability of health systems resources.

It is for this reason that the under-five mortality rate is an indicator of overall child health and is often used as a proxy indicator of more general social and economic development.

Theory of Change

Trends in under-five mortality

Since 1990, the global under-five mortality rate has been cut by more than half, from 85 deaths per 1,000 live births to 39 in 2017. Strengthening health systems in low-income countries to provide quality care and equitable access to the simple, affordable, evidence-based interventions that prevent and treat the most common health challenges can help achieve further reductions in under-five mortality.

Generally, low-income countries have higher under-five mortality rates, with the poorest countries in the world accounting for the majority of all newborn and child deaths.

The under-five mortality rate in low-income countries is approximately 73 deaths per 1,000 live births, almost 14 times higher than the average rate in high-income countries, which is about five deaths per 1,000 live births.

The highest under-five mortality rates are clustered in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. From 1990 to 2013, about three out of four deaths of children under five occur in these geographies.

High under-five mortality is also more common in rural areas, with children in rural areas found to be 34 percent more likely to die before their fifth birthday than their urban counterparts. However the gap has only narrowed slightly over time, due to rural areas experiencing slightly more progress than urban in child mortality reduction.

A similar trend holds when looking at under-five mortality by wealth quintile, as children in the poorest wealth quintile are 92 percent more likely to die before their fifth birthday than those in the wealthiest quintile. However, this gap between quintiles has remained relatively unchanged in the past 20 years.

What can be learned from studying under-five mortality?

Under-five mortality is used as a proxy for the overall status of child health care for a number of reasons:

- It measures outcomes not inputs. For example, the percent of children immunized or the number of doctors in a given country both measure a means to an end—doctors and immunizations help keep kids healthy. However, under-five mortality measures the outcome of these efforts: how many children under five stayed alive.

- High under-five mortality is usually the result of a combination of failures including poor nutrition, low immunization rates, poor maternal health and education, etc. For this reason, it is a powerful indicator of inequity and systemic health challenges.

- Because a majority of these deaths are preventable, the rate reflects, better than any other measure, a lack of access to critical and fundamental quality health care including family planning, pre- and post-natal services, and disease prevention and case management.

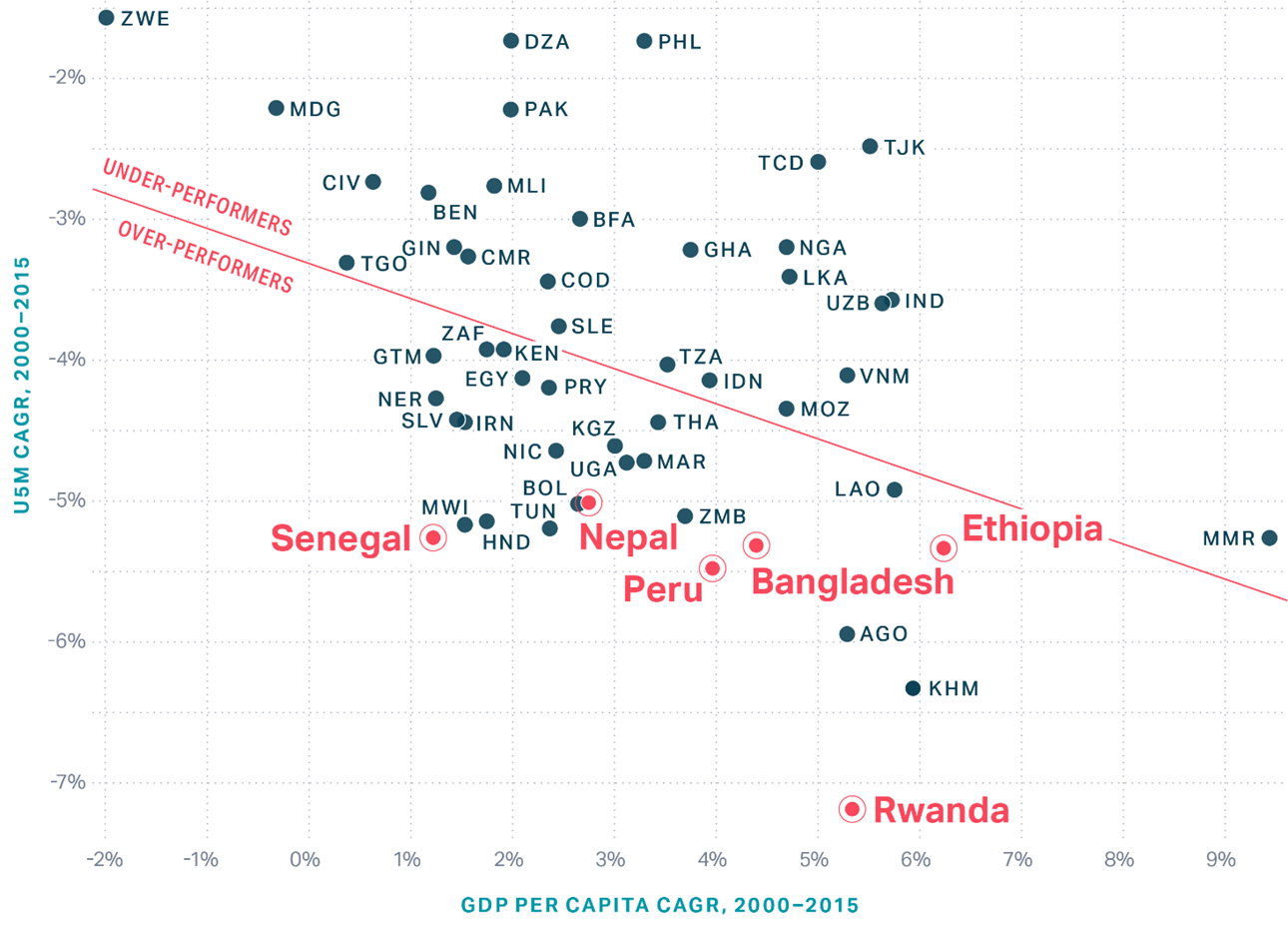

Global U5M change vs GDP per capita change

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD 2017). Seattle, WA: IHME; 2018.