Key Points

Coordinated stakeholders toward shared priorities. Improved coordination across ministries and between the government and external stakeholders toward common priorities. Used a multisectoral approach to encourage pooled resources from partners and donors.

Adapted external strategies to the local context. Formalized structures for input and feedback from representatives at national and subnational levels to ensure interventions and their implementation met the needs of stakeholders and beneficiaries.

Involved community leaders or representatives in health programming. Worked with communities to ensure priorities and programs were responsive to local needs. Engaged with community leaders to build ownership and promote immunization.

Created normative expectations at the community level to generate demand. Disseminated accurate and consistent information through multiple platforms to educate community members on immunization and increase intent to vaccinate.

Coordinated stakeholders toward shared priorities

Zambia took multiple steps to improve coordination across ministries and partners and took a multisectoral approach to the health sector for to enable comprehensive treatment and prevention of prevailing health issues. These actions helped establish the context and enablers for a successful health system.

Developed collaborative approach to primary health care and immunization

Zambia’s Vision 2030, a long-term plan for economic growth, prioritized “equitable access to quality health care by all by 2030” and called for improved coordination across ministries, partners, and donors. In 2008, the Zambian government and other African countries signed the Declaration of Ouagadougou, committing to the revitalization of primary health care. Accordingly, the Zambian government institutionalized the integration of immunization and other primary health care services within the country’s National Health Strategic Plan to ensure the availability of a comprehensive package of services. In addition to vaccination, services such as antenatal care, family planning, HIV counseling, and general referrals would also be offered to the public during outreach events.

This push toward a multisectoral or “horizontal” approach to health was a direct result of influence from the top ranks of the Ministry of Health (MOH), according to interviewees.

“The Minister [of Health] has been very influential in trying to just change the image of the health sector. Child health week is not only about immunization, it’s also about growth monitoring, vitamin A, deworming tablets. So it’s more like you pool resources from various sectors. There are sectors that actually support nutrition in a program, others support immunization, others support other aspects of the child, even pediatric HIV. So you put everything together and then you distribute them and have people go out."

- MOH official

This shift toward a more horizontal approach to health service delivery has increased community access to and attendance at outreach events by creating a catchall “one-stop shop” of essential services and decreasing community members’ travel time for health services. It has also increased collaboration among partners at all levels of the health system.

This collaborative approach extends to the MOH’s interactions with other parts of the government. The Zambian National Development Plan mandates ministries to function in clusters rather than silos. For instance, the district health office may collaborate with the Ministry of Community Development Mother and Child Health to coordinate outreach, with the Ministry of Agriculture to obtain resources such as fuel and motorbikes to access hard-to-reach areas, or with the Ministry of Education to integrate immunization education in curricula or to use schools for outreach sites.

“If you look at the way we have been clustered, it means that we have been given a mandate under that pillar, to work together and collaborate. When we have, for example, health promotion messages, we share with our colleagues in the Ministry of Education and we insist that when they are even conducting regular, teaching lessons with their pupils . . . they actually bring out these issues to do with immunization. These kids are very also effective in transmitting the messages at home.”

- Provincial health official

Engaged faith-based organizations for health service delivery and outreach

The Zambian National Development Plan emphasizes the value of collaborating with civil society organizations. Key informants explained that such collaboration has increased, particularly in the last decade. Nongovernmental organizations such as the Churches Health Association of Zambia (CHAZ) are invited to annual consultative meetings led by the minister of health. These meetings include international and local donors and partners who set priorities on improving health services and evaluating the previous year’s progress.

CHAZ is an example of how deeply the collaborative spirit informs immunization efforts in Zambia. It is a Christian faith coalition, formed in 1970, with the goal of organizing faith-based community groups to have a greater impact on health service delivery. In 1973, CHAZ signed a memorandum of understanding with the MOH to provide broader support for mission health institutions.

Today, CHAZ member health institutions include Catholic and Protestant health facilities representing 17 faith organizations. They include hospitals, rural health centers, and community-based organizations throughout Zambia that provide 40% of national health care services and over 50% of rural health care services. The government supports these facilities with essential medicine shipments, grant funding, and staff. CHAZ health facilities use the government-run vaccine supply chain, although it does have its own warehouse for supplies such as antiretroviral medications and rapid diagnostic tests.

This tight interweaving of CHAZ and government operations is reflected in the organization’s active role in national health planning. It presents at Inter-agency Coordinating Committee (ICC) meetings and is part of the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) technical working group. Additionally, CHAZ is involved at the national level in the development of immunization messaging. CHAZ-run facilities report data through the national Health Management Information System.

“We as technical experts sit down with the ministry’s EPI department to discuss issues and if there is any decision that is needed to be made, we then forward it to the policy makers to look at it, and if it favours the country then they pronounce that decision. CHAZ is part of the EPI TWG [technical working group], and it leads the demand generation part of immunization, mobilizing communities and CSOs [civil society organizations] to play a part in delivering the country's immunization agenda.”

- CHAZ official

Another way the government seeks to ensure broad multisectoral collaboration is by creating mechanisms for community-level systems to offer “bottom-up” input on national health policy through formalized communication channels.

In 2006, Zambia established this approach with the creation of district development and provincial development coordinating committees. These are multiactor platforms that identify development priorities and submit them to the national level for review and approval.

“It’s actually worthwhile noting that our planning has improved quite a lot, because it’s now bottom-up. So, we are the ones that have quite a lot of inputs in these documents.”

- Provincial health official

Expanded the Inter-agency Coordinating Committee to ensure partner diversity and broader mandate

Zambia also developed national partnerships for immunization, as recommended in Global Routine Immunization Strategies and Practices (GRISP). Zambia’s ICC, for example, brings together immunization partners and donors. It plays a significant role in the immunization program by providing oversight for implementation of vaccine initiatives, reviewing evidence to make informed decisions, and lobbying for funding from the government and donors. The ICC also fosters collaboration between the MOH, external partners, and community-level stakeholders. It holds considerable influence on Zambian government agencies and external partners, which facilitates funding, policy decisions, and strategic planning.

A driving factor in the ICC’s success has been its ability to broaden its composition and functions. In 2013, Zambia already fulfilled most of the requirements and recommendations that Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance had established for ICC membership. Some roles, however, were not strongly represented—for example, EPI representatives, MOH officials, and immunization experts.

Zambia’s decision to construct a diverse and robust ICC was consistent with recommendations from a Gavi appraisal in 2016 and 2017. By 2018, when the ICC was considered high functioning, expansive, and diverse, its membership filled all categories sufficiently. Today, that membership includes the minister of health (as chair), as well as partners such as the World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, World Bank, CHAZ, and PATH. The evolution of ICC membership from 2013 to 2018 is outlined in Table 3.

With its multisectoral composition, the ICC provides a forum for coordinating immunization investments, bolsters management of key action points, and supervises the work of appointed technical working groups and task forces. Technical experts, including researchers from the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia and key members of the Zambia Immunization Technical Advisory Group, are also active within the ICC, lending an evidence-based rigor to its decision making. All EPI officers—including representatives for districts and the cold chain, service delivery, and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) programs—are ICC members.

“For the EPI, the Inter-agency Coordinating Committee is a very important organ that plays a role of policy guidelines, policy directions, strategic directions, as well as resource mobilization.”

- WHO staff member

Such a diverse and representative ICC improves collaboration among technical experts, decision makers, and community organizations. It fosters mutual trust and expectations and enables successful uptake of interventions. While it is difficult to attribute increases in vaccination coverage to ICC strengthening, we can determine that the demonstrated commitment from the Zambian government is related to improvements in the vaccine service delivery system.

For its part, Gavi had no doubts on the matter. In August 2018, it issued an appraisal crediting Zambia’s ICC as a “key driver of sustainable coverage and equity.”

Table 3. Evolution in ICC Membership 2013–2018 ,

| Category | 2013 Membership | 2018 Membership |

|---|---|---|

ICC Chair | • Minister of health | • Minister of health • Permanent secretary |

Government Officials | • Expanded Maternal Neonatal and Child Health and Nutrition ICC • Child Health Technical Working Group | • Assistant director, child health and nutrition • EPI manager • EPI officers: cold chain, M&E • EPI district representative • MOH Department of Epidemiology • MOH Department of Planning • MOH Department of Health Promotion • Statistical Office • Zambia Medicines Regulatory Authority |

Zambian Partners | • Churches Health Association of Zambia • Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia | • Chimana College • Churches Health Association of Zambia • Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia • Lusaka School of Nursing • Medical University of Zambia • Zambia Immunization Technical Advisory Group |

International Partners | • Catholic Relief Services • Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance • Japan International Cooperation Agency • PATH • United Nations Children’s Fund • United Nations Population Fund • World Health Organization • World Vision International | • Gavi • John Snow, Inc. • PATH (including the Better Immunization Data Initiative) • Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency • UK Department for International Development • United Nations Development Programme • United Nations Population Fund • United Nations Children’s Fund • US Agency for International Development • US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention • World Health Organization • World Bank |

Beyond expanding its membership, Zambia’s ICC broadened its mandate to other areas of health care. As early as 2010—according to our interviews—the ICC was working to include maternal, newborn, and child health.

In 2017, following a suggestion from Gavi and further discussion at an annual appraisal meeting, the terms of reference for Zambia’s ICC officially expanded to include maternal, newborn, and child health. The ICC now includes leaders from different organizations that work in these areas.

This expansion allowed for a more holistic approach to vaccination, involving antenatal clinics, traditional birth attendants, nurses, and other staff members from health facilities. Activities such as child-growth monitoring and school enrollment also had direct relevance to vaccination efforts. The expanded ICC could now advance all of these activities within its own membership. These changes to the ICC, however, have also reduced the time available to address immunization topics, leading to calls for improving the functionality of the ICC.

The benefits of an expanded ICC membership can be seen in countries with similarly high vaccination coverage. Kenya and Tanzania, with coverage for the three doses of the diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine comparable to Zambia’s (91% and 89% respectively, in 2018), have also expanded their ICC membership. The Kenyan ICC comprises MOH officials and representatives of civil society organization, faith-based organizations, and additional development partners.,, Similarly, Tanzania’s ICC also relies on active collaboration among various key stakeholders, such as the national immunization technical advisory group, faith-based organizations, civil society organizations, development partners, and federal ministries. From this review, we found that the coordination, collaboration, and influence of the ICC are key to the direction and oversight of a country’s EPI programming.

Formalized structures for input and feedback at national and subnational levels

In addition to the ICC, the EPI technical working group provides another important layer of insight and expertise. It allows for more rigorous, evidence-based decision making because it brings the perspectives of remote communities that are far removed from the national government.

The EPI technical working group is composed of four subcommittees: (1) M&E, (2) social mobilization, (3) cold chain and logistics, and (4) service delivery. Each subcommittee is represented in the ICC.

All of these bodies contribute to the M&E process. The MOH considers M&E a key component for decision making at national and subnational levels. A subcommittee within the M&E department at the MOH brainstorms solutions for improving data quality and filters ideas through the EPI technical working group to the ICC. This process facilitates advocacy for new project funding, innovations, and data quality improvement.

Adapted external policies and guidelines to the local context

Zambia adapted external strategies to its local history and context, including the RED strategy for immunization and community health worker strategies. It also leveraged changes in the country’s health system and corresponding adjustments in governance to accelerate coverage.

Tailored the Reaching Every District (RED) strategy to local contexts

One of the most fundamental challenges that Zambia and other lower-income countries face in establishing their vaccination programs is the sheer difficulty of reaching distant populations. Interviewees mentioned that Zambia’s population includes several hard-to-reach communities, including nomadic and migrant populations, island communities, unregistered children, children of seasonal workers, minority religious groups, and residents of urban slums.

To increase equitable access to health care services and improve vaccination coverage, Zambia adopted the Reaching Every District (RED) strategy in 2007. This WHO- and UNICEF-supported approach is intended to be adapted and used by national immunization programs to improve immunization services. RED focuses on empowering districts to manage community-level immunization programming by encouraging partnerships between districts, health facilities, and communities, and promoting the use of data in decision making. While Zambia adopted RED later than most other African countries,,,,,, it learned from earlier adopters and tailored its approach accordingly.

In accordance with RED guidelines, Zambia uses a bottom-up approach to develop action plans: health facilities develop microplans in collaboration with community leaders and representatives, which are then aggregated into a district action plan, then the provincial plan. The action plans identify annual priorities, set objectives, select strategies, determine indicators to monitor and evaluate activities, and estimate required resources and budget. They are developed annually and reviewed quarterly between the districts and health facilities, and between the health facilities and community representatives in order to tailor health activities to local populations. This approach can be challenging when funding is insufficient to support all activities contained in the microplans. To prevent misalignments that contribute to inconsistent implementation, the MOH has agreed to strengthen consultation in budgeting and planning and to improve communication.

The MOH increased the number of health facilities or outreach posts to improve access for remote populations. Through community mapping and CBVs conducting head counts, districts and communities identified the strategic locations of these sites, and in some cases, developed mobile outreach sites. Challenges remain in determining accurate population counts and district jurisdiction for migrant populations and seasonal workers. Key informants frequently discussed logistical challenges due to the lack of transport to outreach sites.

The MOH also developed a Reaching Every Child (REC) manual to provide practical guidelines on community engagement for NHC and other CBVs. Community participation in the planning and implementation of activities has led to strong ownership of the RED strategy, and health workers and volunteers have fully incorporated the strategy into their routine activities. For example, health workers, CBVs, and community leaders are trained on community mapping to identify not only hard-to-reach areas but also to explore the determinants of hard-to-reach populations and the strategies to reach every child.

"When they [health workers] map their catchment areas, they have to identify the hard-to-reach areas within the catchment areas. They have to know the bottlenecks, why those areas are hard to reach, and come up with strategies on how you are going to overcome those bottlenecks. This is a very good strategy, because after that it will help you to plan how you are going to reach out or overcome those bottlenecks. After which now you are able to implement working with various communities. You do not only train health workers but you also orient the community members, the neighborhood health committees, and other volunteers that are found at community level in the same reach-the-child strategy."

- Provincial health official

According to RED, good supportive supervision catalyzes the effective delivery of immunization services. Zambia ensured supervision of routine immunization was carried out at all levels, including communities and health facilities. A 2016 survey of Zambia’s implementation of the RED strategy found that supportive supervision was the best-implemented component.

Another important aspect of Zambia’s RED implementation is the involvement of its ICC in strategic planning, fundraising, and technical oversight. The ICC coordinated funding for RED with partners, and oversaw the implementation of activities, such as community training and bundling of health services. Resources for RED implementation remain a challenge for comprehensive implementation as scaling up continues, however, as noted in Zambia’s 2017-2021 multiyear plan for immunization.

Improved community health worker programming

The WHO Guideline on Health Policy and System Support to Optimize Community Health Workers Programmes identifies key characteristics of high-performing CBV programming. These include providing guidance on clear structures of selection, cascade-based training (i.e., training of trainers), supportive supervision, remuneration, and opportunities for advancement. The guideline also addresses target population size, data collection and use, community engagement, and use of supplies and community resources.

Zambia’s 2010 Community Health Worker Strategy outlines several of these approaches related to the introduction of community health assistants (CHAs). The 2018 strategy includes more details related to a centralized M&E system for CBV data collection and reporting—it harmonized compensation and supervision, formalized and standardized universal training, and specified the package of health services CBVs should provide.

Zambia developed the 2018 Community Health Worker Strategy in collaboration with partners and government sectors, after reviewing best practices from Liberia, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Rwanda and adapting them to Zambia. By identifying gaps and operationalizing an approach to address remaining challenges, the strategy demonstrates Zambia’s ethos of self-reflection and self-evaluation toward its CBV programming.

As the MOH continues to work on implementing the WHO-recommended practices, challenges with CBV programming in Zambia remain. However, there is a clear national intent to integrate CBVs even more fully into the primary health care system.,

Involved community leaders in health programming

Traditional and religious leaders are a vital ingredient in Zambia’s vaccination program. Many of our interviewees—from the community level to the Ministry of Health—noted that vaccine delivery has always required the approval and participation of traditional leaders, who act as gatekeepers to their communities.

"We make sure that the community is fully engaged about the benefit of ensuring that their children are vaccinated and we need to ensure that within the community, the gatekeepers are helping us. Because as health workers, we are usually regarded as foreign, in a way, but when we engage their own people to drive the agenda, that should help. So, for me, the beginning point is community engagement."

- Provincial health official

The involvement of traditional leaders contributes to community ownership, buy-in, and consistent vaccine service delivery at the local level.19 GRISP, RED, and related national strategies all refer to training and engagement of community leaders as an essential piece of vaccine delivery.,,,,,

Traditional leaders were involved in consultations to develop Zambia’s Seventh National Development Plan. They identified key challenges to address, including high poverty levels in rural areas. Traditional leaders proposed that the government ensure that essential services—such as electricity, transport network, schools, and hospitals—are available at the community level nationwide.

Traditional leaders also participate in demand generation. The MOH holds indabas, or formal community meetings, at least once per year at the provincial level with all traditional and religious leaders in the area. The MOH created indabas in 2010 to educate community leaders on vaccination and other community health matters, distribute relevant information to the community, and address prominent misconceptions. Upon completion of an indabas, the ministry and community leaders develop a plan to address health issues in their communities.

Health facility staff meet with community leaders on an ad hoc basis, which is usually every one to three months. The leaders have an opportunity to share challenges faced in their community and suggest solutions. The purpose is to discuss planning and communication for upcoming activities, including child health weeks, the introduction of new vaccines, and the notification of disease outbreaks.

Faith leaders provide space for health promoters to speak on immunization activities during their religious services. Ten to 30 minutes is allocated for health messaging to promote upcoming vaccination activities. Community health workers talk about outreach activities, giving specific details on the time and location of upcoming health education and services for community members.

Generated demand at the community level

Improvements in immunization systems rely on the willingness of individuals to be vaccinated. Increasing the intent to vaccinate first requires generating demand, followed by continuously distributing information to explain how one might get vaccinated. Overcoming vaccination hesitancy requires looking at several components of decision making and behavior change. As high vaccine hesitancy leads to low demand for vaccines, addressing these key components is essential for increasing demand. Additionally, demand for vaccination requires that caregivers and communities trust the safety and efficacy of vaccines, as well as the quality and reliability of services.

Zambia worked to address community vaccine hesitancy and increase both the demand for vaccination and intent to receive vaccination by conducting continuous health education in the community, increasing vaccinator messaging in the media, addressing vaccine-related misconceptions, supporting families who have competing priorities, and utilizing under-five cards.

Educated caregivers on childhood immunization

A major approach to increasing demand for vaccination is continuous health education, wherein community health workers, other frontline workers, traditional leaders, and the media continually provide updated, accurate, and trusted information to community members to reinforce the importance of vaccinating children.

Understanding community values and how these values relate to immunization was important in developing effective campaigns and programs. Frontline worker outreach has played an essential role in connecting parents and community members to the health system in a way that has promoted mutual trust, applied context-specific values, and consequently generated demand for vaccines at individual and community levels.

For example, Zambia’s CBVs are crucial to forming effective community partnerships. Zambia gives community health workers a significant role in educating communities on vaccination. Interview participants discussed Zambia’s emphasis on community engagement and community-driven strategies to combat health challenges. This focus was operationalized in Zambia’s national health strategic plans and national community health worker strategies to formalize and harmonize the roles and responsibilities of frontline workers.,,, Both GRISP and RED recommend working with community health workers to promote demand and mobilize communities for vaccination.,

Although mothers tend to be the primary caregivers in Zambia, immunization messaging and education have also targeted fathers. Men are typically considered the head of the household and are therefore considered the primary decision makers, whereas women are typically in charge of decisions regarding health. Nonetheless, men are encouraged to accompany their partners to health facilities to register their pregnancy and, later, to come to appointments when their children are immunized. To incentivize male involvement, health centers allow women who are accompanied by their partners to skip the queue for antenatal care services and immunization.

These targeted messages and policies have created more vaccination buy-in from men in the community, resulting in greater knowledge and acceptance of immunization at large. In focus group discussions with mothers and fathers, it was clear that immunization was a household priority and the impact of immunization on health and disease was generally well understood.

"Men should fully participate in the well-being of children, because a child doesn’t belong to one person alone. Through sensitization, a lot of men have started bringing their children to the clinic for under-five services and this has brought joy to us and the workload has become lighter."

- Community Health Worker

Parents and grandparents are also a vital audience because the vaccination of children depends on high levels of demand and intent among caregivers.

Shifting cultural and social norms is essential for increasing demand and creating normative expectations to vaccinate children. Such norms evolve through community engagement. This evolution occurred in Zambia through high levels of community engagement in promotional messaging and various forms of outreach through trusted leaders and the media.

Used media to increase knowledge and awareness of immunization

Another crucial amplifier of vaccination messaging is the media. Collaboration with the media has helped Zambian officials ensure effective dissemination of accurate vaccine information. From the national to the community level, Zambia has created a well-structured communication system to engage the public in immunization messaging.

Zambia’s Vision 2030 laid the groundwork for media partnership. The Vision describes information as a “resource” critical to socioeconomic development. Additionally, Zambia’s national strategic plans mention media engagement as a focal point for health improvements, although the plans do not offer specific strategies., Key informants noted that partnerships with the media regarding health topics have been in place for the last 20 years, but engagement has been particularly active within the last decade.

"Whenever you are doing a new vaccine introduction, airwaves and papers and the media will be flooded with messages on vaccines, and particularly the last 10 years, every year, there's been such an event. We always try to ensure that broader immunization messages are incorporated in the event."

- Community Health Worker

At the national level, the health sector and media organizations collaborate to disseminate accurate and timely information. Within the MOH, the Department of Health Promotion, Environment, and Social Determinants is responsible for media engagement. A media liaison officer is posted at the provincial level, and a health promotion officer at the district level connects the radio stations and district health office.

Responded to vaccine hesitancy and competing priorities

Addressing vaccine hesitancy is also important to increase demand. Community health workers, traditional leaders, and other frontline outreach workers not only reinforce vaccine education but also address vaccine-related misconceptions and myths as they come up in the community. Outreach messaging is continuously adapted to address the state of vaccine acceptance in the community. One common misconception is that vaccines can cause severe sickness in children, a fallacy that seems to have been effectively addressed by tailored messaging from community health workers in Zambia.

Competing priorities may also limit some families’ intent to vaccinate their children. Defaulter tracing and continuous follow-up are essential to ensuring that all children are immunized. CBVs conduct defaulter tracing by checking the health facility’s records to identify which children are behind on their vaccinations and following up with their parents.

“This group, CBVs, has got a job of . . . search[ing] for sick children who are not taken to the hospital when sick, or those children who have missed vaccines, and then encourag[ing] the parents to take the child to the clinic.”

- NHC member

If parents miss a vaccination day, an NHC member will visit them to provide information on the benefits of vaccines. If the barrier to access was other responsibilities, the NHC member will escort the child to the outreach event.

"If we find any defaulter, we will query them as to why they didn’t bring the child for vaccination. We make sure that we capture them."

- Community health worker

Sometimes, that education can take the form of a highly tailored intervention with a single vaccine-hesitant household.

“We have role models in the communities we come from. The women know us very well, so much so that wherever you pass, they will stop you and confide in you concerning a neighbor who does not take the child for the under-five clinic. Then you will go and speak with her nicely and she will also go to the clinic; we are very well known.”

- Community health worker

Due to such tailored efforts, Zambia has made significant progress in improving vaccine hesitancy over the years to increase vaccine confidence in communities. As shown in Figure 15, variation in vaccine sentiments reflects regional patterns of coverage for the three doses of the diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine. There remains wide regional variation, however, highlighting the need for locally sensitive planning.

Figure 15: Regional variation in vaccine attitudes

Vaccine Confidence Project Wellcome Global Monitor 2018

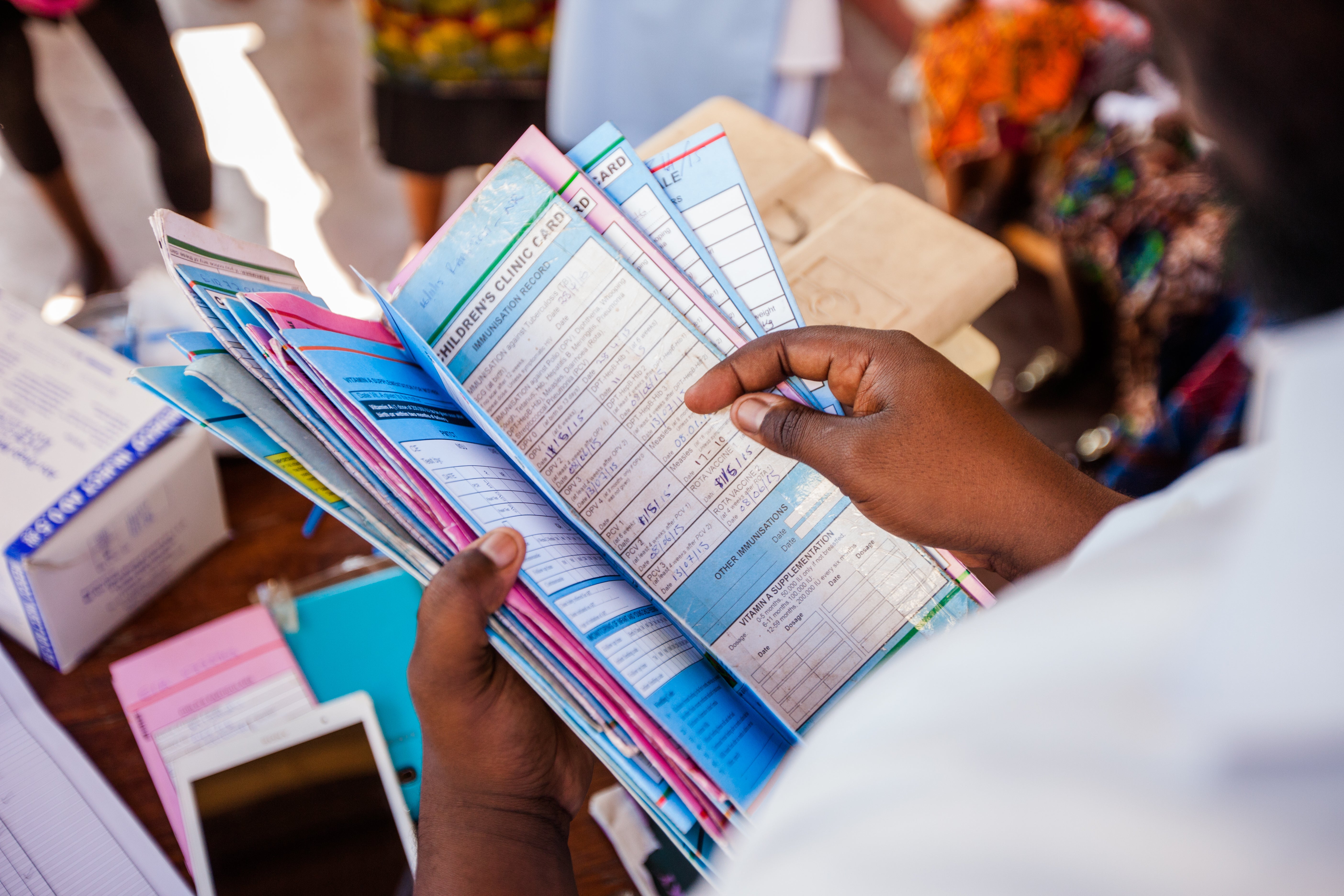

Used under-five cards to increase intent to vaccinate at the community level

One intervention used to reinforce demand is under-five cards, which may be used in addition to more traditional behavior change techniques, such as education, to reinforce intent to vaccinate. These cards list the vaccinations given to children up to age five, and they are intended to be required for school enrollment starting at age seven. The cards act as a nudge for parents to vaccinate their children, list reminders for upcoming appointments, and include additional messaging on child health priorities.

Children under five who do not have all required vaccinations listed on their under-five cards receive catch-up doses through immunization outreach activities. Schools use special immunization weeks to help ensure students are properly vaccinated. During outbreaks, representatives from the MOH visit children at school and immunize them against the pathogen. Under-five cards must also be shown when registering for the national final examination in grade 12 and when applying for a national registration card.

Some key informants at the district and community levels reported that the cards are required for school enrollment in their area and are effective in reinforcing intent to vaccinate among parents. They also reported that inconsistencies across the country in how strictly immunization regulations are applied may limit the practicality and success of this approach.