Community Health Workers in Ethiopia

Political commitment at the highest level and across government has strengthened Ethiopia’s community health worker program.

CONTENTS

Quick Downloads

KEY INSIGHTS

For leaders looking to understand, adapt, and replicate Ethiopia's success, our research identified five key insights:

- Problem-driven approach to program design

- Political leadership

- Donor coordination

- Extended and structured piloting period

- Commitment to evaluation and adaptation

Problem-driven approach to program design

In the 1990s and early 2000s, low health-seeking behavior in rural areas, a lack of access to health care facilities, and a shortage of health care workers meant that Ethiopia had some of the worst health indicators in the world.

Ethiopia examined its disease burden and saw that nearly half of all deaths were easily preventable or treatable such as those from malaria, diarrhea, rotavirus, and pneumonia. Ethiopia developed a package of preventive and curative services that closely mirrors this disease burden in rural Ethiopia. The range of care provided by Ethiopia’s CHWs—which includes treating the leading causes of preventable deaths along with severe acute malnutrition, HIV (with PEP), and TB (with DOTS)—is designed to provide maximum impact.

Political leadership

Leadership at the highest level was the catalyst for the success of Ethiopia’s community health worker program.

National political leadership from the most senior ranks aligned officials across ministries, geographies, and levels of government to ensure financial support, encourage and streamline donor commitments, support a multi-sectoral strategy, and mainstream the initiative.

Political leaders demonstrated their support for the program in public comments and budgets, and institutionalized it in public policy, after discussing the program’s design, implementation, and development. This consistent engagement reinforced the notion that this was a national priority. The program became, in the words of one informant, “Ethiopia’s brand.”

Donor coordination

Ethiopia’s program was, from the outset, “donor supported, not donor driven.”

Ethiopia’s rapid progress in strengthening its primary health care system was in large part due to its ability to attract external resources and to manage donors effectively, channeling their resources and expertise to support the country’s flagship program.

Ethiopia’s strong coordination of donors aligned donors’ traditionally vertical, disease-specific funding with government’s horizontal primary healthcare priorities to address the systemic failure of the health system. Ethiopia’s mantra in its interactions with donors was: “One Plan, One Budget, One Report.” The government developed the plan for the program, created the budget, and would issue regular reports on progress. The Health Extension Program has been, from its inception, a government-led, donor-supported program.

An extended and structured pilot period

An extended and structured pilot period allowed Ethiopia to develop regional and national consensus and provided a tried and tested framework for implementation.

Ethiopia’s success with developing, implementing, and refining one of the largest community health worker programs in the world has its roots in lessons the country learned during half a century of community health worker programming and pilots.

The country’s Health Extension Worker program began as a pilot in 1998 in the northern Tigray region, with its population of five million. During this four-year pilot, Tigray experimented with innovations, tested global best practices locally, and developed frameworks and policies that would eventually guide scaling.

Given Ethiopia’s decentralized approach, Tigray’s officials made a point of sharing their learnings within the region and across the country. As Tigray’s health outcomes improved, interest in adopting the program nationally grew.

Commitment to evaluation and adaptation

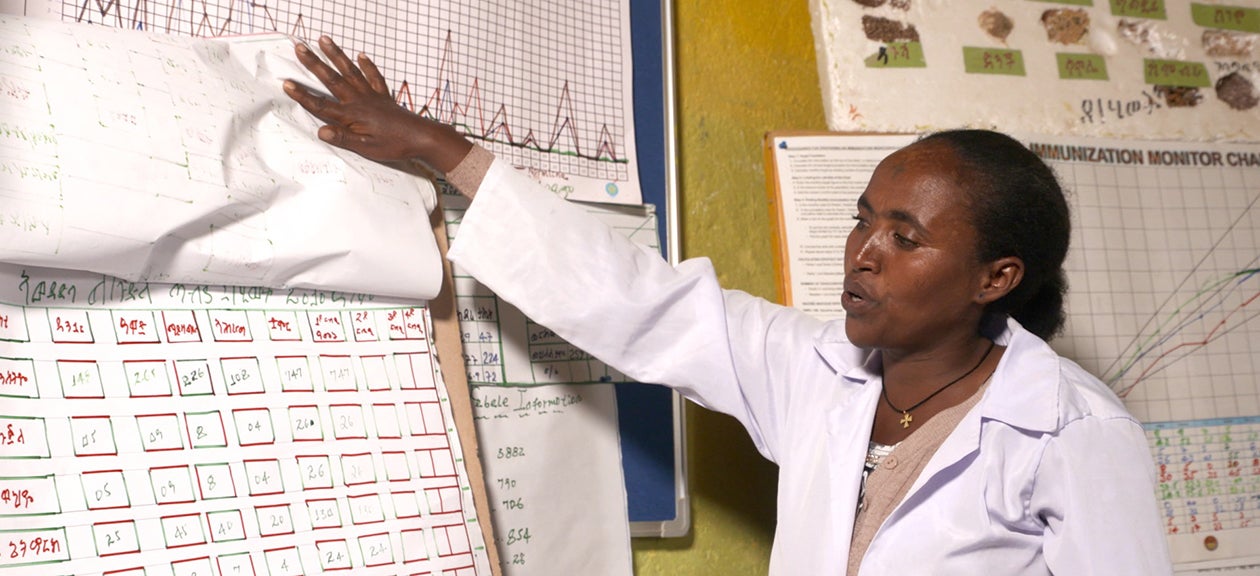

Ethiopia established multiple levels of monitoring mechanisms to inform regular evaluations and modifications.

Ethiopia demonstrated a commitment to continually evaluate, share findings, solicit feedback, and adapt the program in response to challenges, evolving domestic and international evidence, and learning exchanges.

While many programs are monitored and refined as necessary to improve impact, Ethiopia’s Health Extension Program is unusual in that the government established multiple monitoring mechanisms functioning at various levels, from the family level to the village level on up, and used timetables for sharing data, with the expectation that this feedback would ensure opportunities for continuous improvement.

Community Health Workers in Ethiopia

Ask an Expert

Our team and partners are available to answer questions that clarify our research, insights, methodology, and conclusions.