Key Points

Ethiopia has embedded its community health worker program in the broader health system.

Programming includes both curative care and preventive care.

40,000 professional Health Extension Workers, supported by another 3 million part-time volunteers, work in their communities to change norms and improve health.

In 2004, Ethiopia launched an unprecedented pair of initiatives to improve its dismal health indicators.

First, the government drastically increased the number of health centers across the country with the Accelerated Expansion of Primary Health Care Coverage.

Second, recognizing that even with this expansion, the government still did not have the physical and human infrastructure to meet demand for healthcare, it expanded the footprint of this brick and mortar network by training 30,000 villagers (40,000 by 2015) to work in the 15,000 (16,000 by 2015) newly established health posts as Health Extension Workers. Two Health Extension Workers were assigned to work in each Health Post, a modest structure erected by the community with government support. The pair of Health Extension Workers (HEWs) in each Health Post served 3,000-5,000 residents.

These Health Extension Workers functioned as the lowest level of the formal national health system and were Ethiopia’s bold attempt to provide its citizens, no matter where they lived, with primary health care. It is important to realize that these workers didn’t just sit in the health post waiting for, and treating, patients. In fact, they were expected to spend about 75 percent of their time out in the community initially, though this changed over time. Much of the HEWs’ work outside their health post involves visiting families in their homes to create demand for healthcare in communities that have been accustomed to functioning without it. In the early days of the program, this involved educating communities about good health and hygiene practices that prevent illness, like exclusive breastfeeding. As demand for healthcare increased, some of the behavior change communication work shifted from Health Extension Workers to part-time volunteer members of the Health Development Army.

A 2017 study found that Ethiopia’s simultaneous combination of investments in primary health care facilities and low-level, community-based staff was critical to the success of its health sector and, ultimately, to achieving the health-related MDGs.

There are a number of programmatic elements that made the Health Extension Program particularly impactful in the Ethiopian context. We discuss each in this section:

Health Extension Worker Profile and Training

Global and domestic research informed Ethiopia’s standards for the profile and training of Health Extension Workers (HEWs). All HEWs are female, because villagers view women healthcare workers as more acceptable and approachable than male healthcare workers. HEWs have at least a tenth-grade education and live in the communities they serve. Once selected by their fellow villagers, HEWs receive one year of full-time training in a Ministry of Education technical and vocational training school before they begin work in their local health post. As full-time government employees, they receive a monthly salary of up to $120.

At the introduction of the Health Extension Program, HEWs received primarily classroom-based training and emerged with limited practical skills. An independent 2007 evaluation identified shortcomings in the performance of HEWs and recommended they receive more frequent practical training and regular supportive supervision focused on improving their clinical competencies. Another 2007 independent evaluation found that 78 percent of HEWs felt the types of duties and responsibilities they were expected to perform required more training than they had received.

Initially, NGOs jumped in to fill these gaps by offering in-service training programs. These uncoordinated efforts resulted in redundancies in training, skill gaps, and a disruption of the delivery of care.

How the Ethiopian government handled this problem is another example of their adept coordination of donors and other development partners. The government restricted NGOs from providing direct training to HEWs, but convened partners to develop an in-service integrated refresher training (IRT) curriculum in 2009. What emerged was a 30-day training module that improves HEW's knowledge of the basic service package, updating them on new service elements.

“Before IRT was introduced, every NGO program developed their own training materials. For every training, HEWs were called to attend… as many as 15 trainings a year, some for five days; almost one-third to fifty percent of the HEWs’ time was spent to come for training in cities…”

Research participant from the NGO sector

Now, HEWs are eligible to take additional integrated refresher trainings that last 15-30 days, every two years. A study found that from 2011-2014, more than 80 percent of HEWs had completed IRTs in the management of possible severe bacterial infection, iCCM and maternal, newborn, and child health, while a smaller percentage had received re-training on other topics. However, quality of care remains a pressure point for the program.

“…the awareness of the community is increasing. Educated young people… seek more services, quality services… in some areas, the awareness of the community is greater than the HEW’s. There is a need to upgrade the HEW to nurses (Level IV). The demand from the community is very challenging and rapidly evolving.”

Multilateral development partner

To address this, and offer HEWs opportunities for career advancement, the government is further expanding training available for HEWs. HEWs interested in expanding the services they offer can enroll in a second year-long training program focused on providing more sophisticated curative services. As of 2017, nearly 30,000 HEWs had completed the additional training. The Ministry of Health has set the goal of upgrading a total of 35,000 HEWs. These more highly trained HEWs earn a higher wage. They are called level IV HEWs, while regular HEWs are known as level III HEWs.

Basket of Services

Complete Health Extension Program Service Package

At the outset of the Health Extension Program, Health Extension Workers (HEWs) were tasked with a package of 16 preventive services - all of them drug-free. In addition to guarding against any possible misuse of antibiotics, the initial focus on drug-free prevention minimized program costs - critical for Ethiopia’s economy, still struggling at the time. Each preventive service was a response to a major disease that remained unchecked in rural communities, demonstrating Ethiopia’s problem-driven approach to program design.

ORIGINAL LEVEL III HEALTH EXTENSION PROGRAM SERVICES PACKAGE

| HYGIENE & ENVIRONMENTAL SANITATION | DISEASE PREVENTION & CONTROL | FAMILY HEALTH SERVICES | HEALTH EDUCATION & COMMUNICATION |

|---|---|---|---|

Proper and safe excreta disposal system Proper and safe solid and liquid waste management Water supply safety measures Food hygiene and safety measures Healthy home environment Arthropods and rodent control Personal hygiene | HIV/AIDS prevention and control TG prevention and control Malaria prevention and control First Aid | Maternal and child health Family planning Immunization Adolescent reproductive health Nutrition | Cross-cutting |

Data source for table: Bilal, 2014; Wang, 2016; Perry, 2016; Perry, 2017; USAID, 2017; Ramana and Workie, 2014; El-Saharty, 2009

Within a few years of launch, domestic and international research and pilot testing proved HEWs could safely provide curative services, including first-line antibiotics. At the same time, donors gained confidence in the program and began to support it. With this new research, increased funding from donors, and an increasingly robust economy, Ethiopia decided to expand the basket of services to include key curative services that more precisely mirrored rural Ethiopia’s disease burden. HEWs began treating the leading causes of preventable deaths across rural Ethiopia: malaria, pneumonia, diarrhea, severe acute malnutrition, HIV (with PEP), and TB (with DOTS).

Later, community-based newborn care, which includes antenatal and postnatal visits to identify and treat sepsis, and long-acting contraceptives were added to HEWs' services. The final basket of services provided by HEWs is another example of Ethiopia’s problem-driven approach to program design.

The inclusion of these curative and more sophisticated services has increased the complexity of HEWs' tasks. Not surprisingly, as their responsibilities multiplied, HEWs began reporting feeling overburdened. Experts worried the system was overtaxed and might begin to fray. The government responded by adding powerful new allies for HEWs: model families and the Health Development Army.

Model Families and the Health Development Army

In 2006, the government of Ethiopia magnified the reach of the Health Extension Program by adding a new element: model families.

This concept was based on an earlier Ethiopian Agricultural Extension Worker Program, which trained locally elected farmers (two per village) as agricultural development agents. Selected farmers worked in their communities to model improved agricultural practices and provide training on modern farming methods, such as the use of fertilizers, and improved seeds. The program improved agricultural production, increased food security, and sparked sustainable economic growth that many see as the foundation of Ethiopia’s current robust economy.

The agriculture program was influential because of its unique theory of change, based in part on the premise that farmers, just by publicly modeling best practices, would influence the behavior of their neighbors. This approach of training villagers to actively model best practices to their peers was adapted to inform the development of the “model family” in the Health Extension program.

Volunteer model families have become a critical part of the Health Extension Program. They receive 96 hours of training in healthy practices such as exclusive breastfeeding of newborns, and in themes like the importance of immunizations. Their main task is to serve as positive outliers in their community. These early adopters of best hygiene and health practices encourage their neighbors to follow and as a result, slowly change their community’s norms for the better. The scale of this program is important to appreciate. As of 2011, nearly 70 percent of all households across the entire country have received model family training.

In 2011, as HEWs’ responsibilities proliferated and surveys showed the need for further modifications in how they worked, the government of Ethiopia added yet another layer of support for HEWs: the Health Development Army. These three million volunteers, who have gone through the Model Family training, provide a more formal mechanism for influencing behaviors. The Health Development Army engages groups of households in their communities to engage in weekly meetings to discuss issues related to children’s health, hygiene, nutrition, antenatal care and maternal health. They also support HEWs with lower-level tasks, immunization campaigns, community mobilization, managing appointments, household visits, and record keeping. Included in the Army were previously existing but uncoordinated reproductive and family planning volunteers. The Health Development Army works with large numbers of Ethiopian households - nearly one in six - within the Health Extension Program’s scope.

HEP PROGRAM CHARACTERISTICS TABLE

| CHARACTERISTICS | HEALTH EXTENSION WORKER (HEWs) | HEALTH DEVELOPMENT ARMY VOLUNTEERS (HDAV) |

|---|---|---|

Scale | ~40,000 (2017) | ~3,000,000 (2017) |

Ratios |

|

|

Qualifications |

|

|

Selection |

|

|

Training |

|

|

Services Offered |

|

|

Roles + Responsibilities |

|

|

Incentives |

|

|

Supervision |

|

|

Data source for table: Bilal, 2014; Wang, 2016; Perry, 2016; Perry, 2017; USAID, 2017; Ramana and Workie, 2014; El-Saharty, 2009

Integration into the Formal Health System

Researchers who systematically reviewed four large community health worker programs in Ethiopia, Brazil, India, and Pakistan, found that Ethiopia’s program was the most thoroughly integrated into the wider health system, benefitting greatly from that integration.

To understand how Ethiopia’s Health Extension Program is embedded within the larger primary health care system, it is helpful to understand the structure of Ethiopia’s health system.

Ethiopia has a three-tiered health care structure. At the bottom are the health posts staffed by two HEWs. Five health posts report up to one health center. The chain of command rolls up through this basic primary health care unit of five health posts and one health center, through to zonal hospitals, and all the way up to specialized referral hospitals.

Health Extension Workers are the closest to the ground, and are the most widely distributed and accessible part of Ethiopia’s health system. They serve as the key that connects Ethiopia’s rural communities with the broader health system meant to serve them.

The primary health care unit

HEWs are embedded into the health system in three key ways: they make and receive patient referrals, they are supervised by health staff at local centers, and the routine health information they collect about their patients is integrated into the federal health management information system. This improves patient care and outcomes.

But it would be a mistake to think of them as purely Ministry of Health staff. They are also members of the village council. The layers of supervision HEWs receive reflect their position as critical connectors between communities and the health system. Initially HEWs were supervised by village councils (who help run communities) and district health administrators. Later, yet another level of supervision was added: a team at the nearest primary health care center. This clinical support was added to improve HEWs’ motivation and patient care. HEWs’ clinical supervisory teams include a health officer (who serves as the main point of contact), a public health nurse, an environmental/hygiene specialist and a health education specialist.

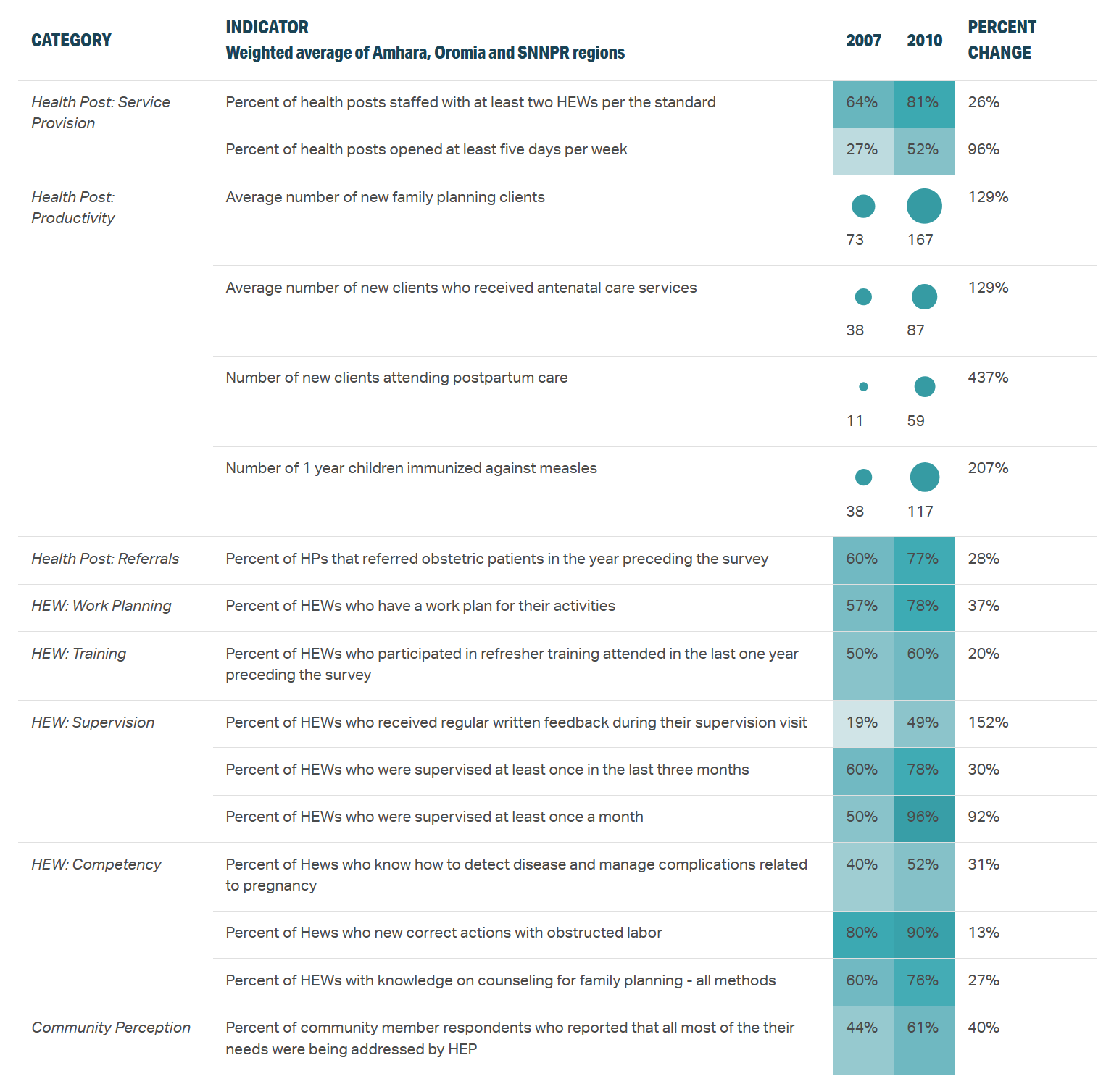

This change strengthened HEWs' connections to the wider health system and improved rates of supervision and quality of care. The percentage of HEWs who had been supervised at least once a month increased from 50 percent in 2007 to 96 percent in 2010. The percentage of HEWs who knew how to detect disease and manage complications related to pregnancy increased from 40 percent to 52 percent in the same period. And the percentage of community member respondents who reported that all or most of their needs were being addressed by HEWs increased from 44 percent in 2007 to 61 percent in 2010.

PERFORMANCE EVALUATED IN 2010

Data source for table: HEP National Impact Evaluations: Summary Performance Data Table

Patients can access the entire health system through the health post in their communities, which are staffed by two HEWs. From these modest health posts, they can be referred up to higher level facilities to receive more complex care, as needed.

Behavior Change Communication

The Health Extension Program, from its very inception, aimed to accomplish much more than merely vaccinate children, provide pregnant women with check-ups, and treat sick children. The program’s goal included fundamentally changing rural communities' thinking on disease prevention, family health, hygiene, and environmental sanitation.

“The goal was to put knowledge and power - and, ultimately, responsibility - in the hands of local people.”

Former Health Minister Kesete Admasu

To foment this change, at the start of the program, HEWs were expected to spend 75 percent of their time in their communities and 25 percent of their time at their health posts. That ratio reflects the importance placed on behavior change communication in the key areas of children’s health, hygiene, nutrition, antenatal care, and maternal health.

HEWs and, later, Model Family and Health Development Army members, encouraged their communities to take action to improve their health, including building and using pit latrines, separating animal sheds from family housing, breastfeeding their children, improving hygiene and ventilation in their kitchens, seeking antenatal care and giving birth in a facilities with skilled attendants.