Key Takeaway: While Morocco has made remarkable progress—having reached, or on track to reach, the Sustainable Development Goal targets—certain communities lag behind. Targeting poorer and rural communities will be essential as Morocco seeks to attain the lowest levels of neonatal and maternal mortality.

In assessing progress in reducing neonatal and maternal mortality in Morocco, it is valuable to contextualize this progress in comparison with peer countries and international targets. Although lessons from Exemplar countries like Morocco are designed to provide insights for peer countries, Exemplar countries themselves can still benefit from cross-country comparisons. Positioning progress on an international scale is important to understand trajectories of mortality reduction, potential future challenges, and progress toward global targets.

The maternal and peri-neonatal mortality transition framework

Multi-country comparison

Learnings from a multi-country analysis, using an integrated maternal, neonatal, and stillbirth mortality transition framework, could prove useful as Morocco looks to further reduce neonatal and maternal mortality. In this framework, mortality levels are categorized into five phases, with phase I indicating higher mortality levels and phase V indicating lower mortality levels. The transition framework is a tool that can be used to benchmark country progress and chart a path to progress—with distinct drivers mapped to successive steps.

As shown in Figure 20, from 2000 to 2020, Morocco progressed from phase III to phase IV in the integrated maternal, neonatal, and stillbirth mortality transition framework. As Morocco progresses through phase IV, the framework can yield insight into the characteristics that are usually observed as countries advance into phase V. This framework may also be useful in identifying challenges commonly experienced by countries as they seek to achieve the low mortality levels experienced in phase V.

Stepwise trajectory to progress

Through our multi-country analysis, we identified key factors that were associated with advances along this transition, shown in Figure 21. Advancements beyond phase I were often linked to contraceptive use and fertility declines. Further progress through phase II and III often occurred as coverage of antenatal care, in-facility delivery, skilled birth attendance, and postnatal care improved, in part due to an expansion of physical infrastructure and human resources for health. This often led to a transition in causes of death in phase III, as preventable infections represent a shrinking portion of deaths, whereas indirect causes such as underlying maternal health conditions contribute a growing share of deaths. Finally, transitions to phase IV and V frequently reflect a prioritization of health equity, as vulnerable communities gain access to interventions previously only accessible to richer, more urban, or highly educated communities.

Morocco increased health service coverage through the 1990s and 2000s, with higher rates of contraception, antenatal care (ANC), institutional delivery, and C-section. The 2008 Acceleration Plan removed user fees from delivery services and obstetric care, helping to further accelerate coverage of key maternal, newborn, and child health (MNCH) services. The 2008 Acceleration Plan also improved the quality of physical infrastructure and service delivery, as well as the skill level and quantity of human resources for health. Though Morocco’s policy actions have helped to reduce infectious and preventable causes of death, further action may be needed to decrease maternal deaths from hemorrhage and eclampsia as well as neonatal deaths from prematurity and birth asphyxia. Now in phase IV, addressing equity gaps will also be crucial for advancing to phase V in the transition. The following sections of this narrative will highlight trends in health care equity, focused on residence and wealth quintiles.

Figure 21: Integrated Maternal, Neonatal, and Stillbirth Mortality Transition Progression

Boerma, Ties, et al. "Maternal mortality, stillbirths, and neonatal mortality: a transition model based on analyses of 151 countries." The Lancet Global Health 11.7 (2023): e1024-e1031. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(23)00195-X/fulltext#seccestitle10

Progressing toward the Sustainable Development Goals

Morocco has achieved remarkable reductions in the neonatal mortality rate (NMR) and maternal mortality ratio (MMR) over the past two decades, positioning the country well with regards to the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets as shown in Figure 22.

According to United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME) estimates of NMR, the country achieved the SDG target of 12 neonatal deaths per 1,000 live births in 2020. If Morocco continues the same rate of progress experienced between 2000 and 2021—an average annual reduction rate (AARR) of 2.7%—the NMR is projected to decline to 8.7 neonatal deaths per 1,000 live births by 2030, which is substantially lower than the SDG target.

While United Nations Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group (UN MMEIG) estimates indicate that Morocco has not yet attained the national SDG target of 44.6 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, the country is on track to reach this target by 2030. If Morocco maintains the same rate of progress experienced between 2000 and 2020—an AARR of 5.9%—Morocco would reach the SDG target in 2028. If Morocco maintains the slightly faster speed of MMR reduction experienced since 2010, the country would reach the SDG target by 2027.

While these projections include several assumptions—most notably that the rate of progress in Morocco will be the same in the future—this evidence suggests that Morocco is well positioned to achieve the SDG targets, a remarkable achievement. Beyond these targets, learnings from the integrated mortality transition framework suggest that continued mortality reductions will be achieved by targeting vulnerable communities such as those who are poor or live in rural areas.

Equity trends for key reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health indicators in Morocco

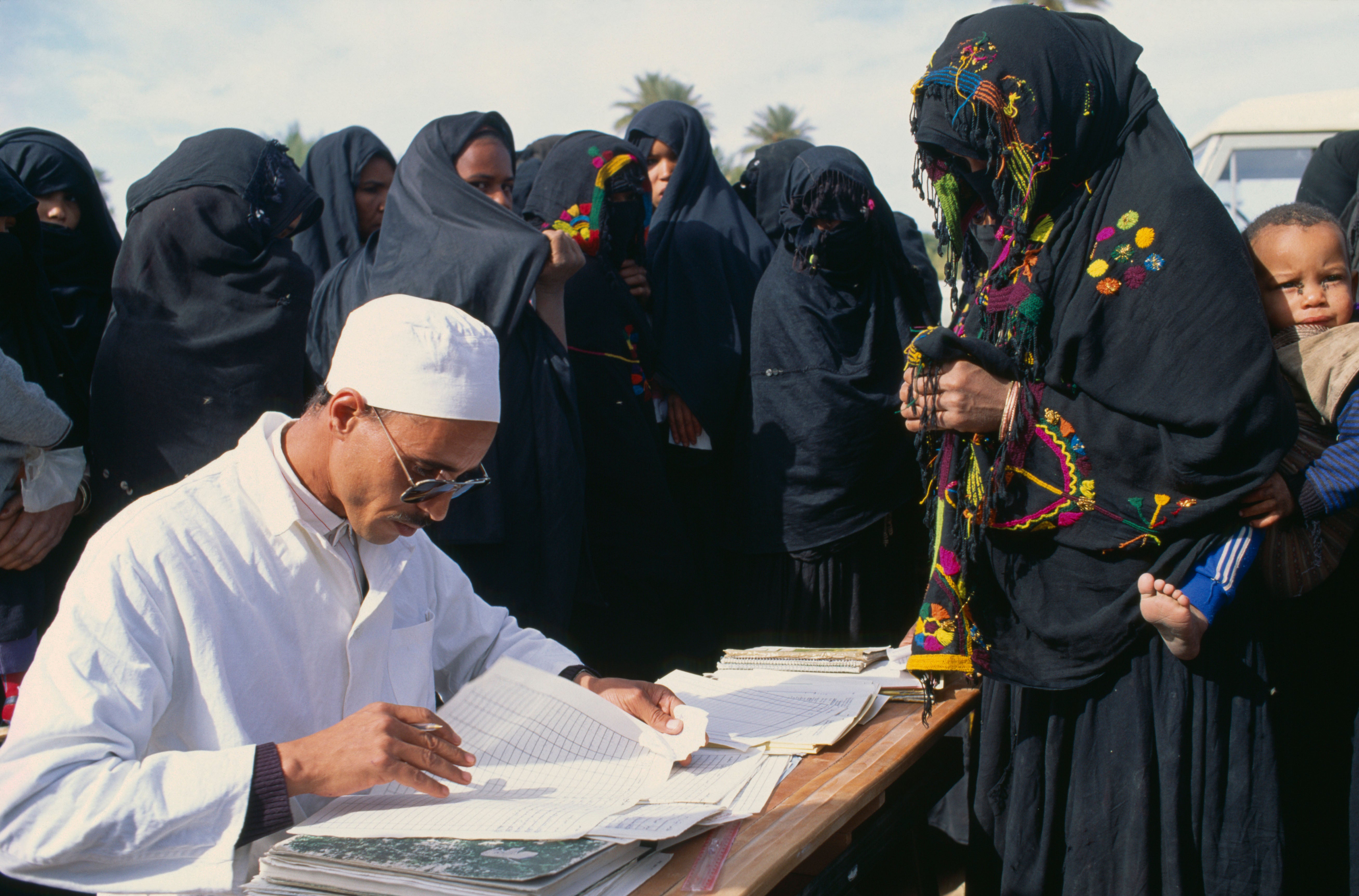

As countries such as Morocco seek to continue reducing neonatal and maternal mortality levels, the integrated mortality transition framework suggests that reaching vulnerable communities will be a crucial component of progress. This framework indicates that narrowing equity gaps is especially key for countries looking to advance from phase IV to phase V, including Morocco. As such, this section considers trends in the equity of several maternal and newborn health indicators in Morocco.

Family planning

According to Morocco’s 1992 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), there were substantial equity gaps in the use of modern contraception among married women, as shown in Figure 23. At the time of this survey, the modern contraceptive prevalence rate married among women in urban areas was 18.1% higher than for women in rural areas., Similarly, married women in the wealthiest quintile were over 2.5 times more likely to use modern contraceptive methods than married women in the poorest wealth quintile.

These gaps had been substantially mitigated by Morocco’s 2003–2004 DHS, with similarly narrow gaps identified by Morocco’s 2018 Enquête Nationale sur la Population et la Santé Familial (ENPSF)., According to this most recent ENPSF survey, the gap in the modern contraceptive prevalence rate was 5.2% between urban and rural communities, and 2.4% between the wealthiest and poorest quintiles.

By a wide margin, the 2018 ENPSF found that the pill was the most common method of modern contraception in Morocco across residence and wealth status. However, among women who lived in urban areas or were wealthier, intrauterine devices were notably more prevalent. For example, 7.2% of the wealthiest women reported having an intrauterine device, whereas only 2.0% of the poorest women reported using this method.

Geographic disparities in access to family planning services remain across Morocco’s regions. According to the 2018 ENSPF, the populous region of Tanger-Tétouan-Al Hoceima has the lowest modern contraceptive prevalence rate among married women at 38.9%, followed by the more rural and less populated region of Guelmim-Oued Noun at 47.7%. The highest rates of contraceptive use among women are in Marrakech-Safi at 68% and Béni Mellal-Khénifra at 65.4%.

Morocco has continuously prioritized reproductive health access since the 1990s, and more recently in the 2008 Acceleration Plan and 2012 Consolidation Plan. The government has focused on household-based delivery of family planning services, and has made contraceptives accessible to women of lower socioeconomic status and in rural areas—helping reduce the size of equity gaps in family planning uptake. Moving forward, expanding the service options for modern contraceptive methods for all populations, including non-married women, may help to encourage usage broadly. Examples include introducing other long-acting reversible methods such as self-administered injectables and promoting the use of existing methods in underserved communities.

Antenatal care

While family planning services became increasingly equitable, ANC coverage continued to be substantially higher among urban and wealthier populations as shown in Figure 24. At the time of Morocco’s 1992 DHS, the percentage of pregnant women who received antenatal care at least four times (ANC4+) was 16.6% higher among urban communities than rural communities and 27.3% higher among the wealthiest quintile than the poorest quintile. By Morocco’s 2018 ENPSF, these margins had widened slightly to 20.5% and 29.7%, respectively. While ANC4+ coverage increased substantially in both rural and urban communities and across wealth quintiles, progress in rural and poorer communities was not rapid enough to narrow the existing coverage gaps.

Across demographics, there are also differences in the provider of ANC and the type of facility. For instance, Morocco’s 2018 ENPSF indicates that among pregnant women who received ANC from a qualified provider, 90.1% of those in the wealthiest quintile saw a doctor while only 73.9% in the poorest quintile saw a doctor. This indicates that ANC for poorer women is more likely to be provided by nurses and midwives. In terms of type of facilities, pregnant women in the poorest quintile were more likely to receive ANC at a public health center or birthing center, while women in the wealthiest quintile were more likely to receive ANC at a private clinic – which tend to be more expensive.

In terms of geographic variation, rates of ANC4+ coverage in the majority of regions in Morocco are between 59% and 65%, suggesting relative equality in access. However, two regions lagged behind in ANC4+ coverage as of 2018: Tanger-Tétouan-Al Hoceima at 54.3% and Béni Mellal-Khénifra at 45.6%. Both regions have large populations (3.6 million and 2.5 million, respectively, in 2014) and are relatively urban (60% and 49%, respectively).

ANC coverage and ANC quality improvements have increased with the 2008 Acceleration Plan and 2012 Consolidation Plan. The removal of user fees from obstetric services via these policies contributed to increased ANC coverage in lower wealth quintiles and rural areas. Mobile health teams have also supported the delivery of ANC in rural and remote areas. As Morocco advances through the transition framework, prioritizing strategies that continue to reach the most vulnerable groups in society will be crucial to increase coverage.

Though institutional delivery rates are high, Morocco is experiencing a gap between ANC4+ coverage and institutional delivery rate. Though 86.1% of women deliver in a facility, ANC4+ coverage is only 60.9%, meaning that a substantial proportion of women who deliver in a health facility are receiving ANC fewer than four times. The gap between institutional delivery and ANC4+ coverage is 24.9% for the poorest quintile. This same gap is 24.6% for the wealthiest quintile, suggesting that the gap between ANC4+ coverage and institutional delivery rate exists across equity gradients. The transition framework can be helpful to understand where peer countries are in terms of health service coverage: countries in phase IV of the framework typically have a median of 87% ANC4+ coverage. Continuing to improve ANC coverage across all communities may be a priority for Morocco as the nation transitions from phase IV to phase V in the transition framework.

Institutional delivery

Progress in improving institutional delivery in Morocco has been particularly rapid among rural and poorer communities, contributing to the narrowed equity gaps shown in Figure 25. At the time of Morocco’s 1992 DHS, women in the wealthiest quintile were 14 times more likely to deliver in a health facility than women in the poorest quintile, with an institutional delivery rate of 70.6% compared to 5.0%. Institutional delivery among the poorest has experienced remarkable progress, reaching 68.4% as of Morocco’s 2018 ENPSF, with the equity gap less than half of what it was in the 1992 DHS.,

Similarly, the gap in institutional delivery between urban and rural populations has also halved between Morocco’s 1992 DHS and 2018 ENPSF., As of Morocco’s 2018 ENPSF, 96.6% of deliveries in urban areas took place in health facilities while 74.2% of deliveries in rural areas occurred in health facilities. Among women who did not deliver in health facilities, Morocco’s 2018 ENPSF identified that among urban and rural communities there were notable differences in reasons for delivery elsewhere. While only 0.1% of women in urban communities reported that distance from health facilities was their main barrier to institutional delivery, 19.3% of women in rural communities reported this was their main barrier. In contrast, a husband or family member’s preference for home delivery was the main barrier to institutional delivery for 7.8% of women in urban areas who did not deliver in facilities, compared to only 2.2% of such women in rural areas. In terms of variation by geography, the majority of regions in Morocco have institutional delivery rates between 84% and 95%. However, regions Drâa-Tafilalet and Béni Mellal-Khénifra have a lower proportion of women delivering in facilities at 66.6% and 75.8% of women, respectively. Drâa-Tafilalet has a higher topography, lower population density, and a lower rate of urbanization (35%) compared to Morocco overall.

Several key policies have impacted institutional delivery rates, such as the removal of user fees from delivery care and C-section in the 2008 Acceleration Plan, and broadened removal of user fees for other obstetric complications in the 2012 Consolidation Plan. The introduction of obstetric ambulances for rural settings, mobile medical teams, and maternity waiting homes have also encouraged and enabled women in rural areas to deliver in a facility. Continued focus on the programs that target rural areas and lower-income families will help to increase access to MNCH care and close the equity gaps.

Cesarean section

Trends in C-section coverage over time indicate that the procedure has become more common overall, especially among wealthier and urban communities. As shown in Figure 26, rates of C-section have increased substantially across residence and wealth status in Morocco over recent decades, including for poorer and rural groups.

At the time of Morocco’s 1992 DHS, C-section was generally only available to wealthier and urban communities, occurring in less than 1% of births among the poorest quintile and rural populations. At this time, the C-section rate was similarly low for all wealth quintiles except for the wealthiest, which had a C-section rate of 5.9%—more than double the rate of 2.6% for the second wealthiest quintile. By Morocco’s 2018 ENPSF, C-section had become remarkably more accessible to segments of the population who were poorer or lived in rural areas. During this period, the C-section rate among the poorest quintile increased from 0.8% to 9.6% while the C-section rate among rural communities increased from 0.9% to 12.9%.

In parallel, C-section rates among wealthier and urban populations have also increased, to levels beyond what WHO recognizes as beneficial for the reduction of newborn and maternal mortality. As of Morocco’s 2018 ENPSF, the C-section rate among the wealthiest quintile was 29.4%—an elevated level linked to the higher rate of delivery in private hospitals among the rich.6 Morocco’s 2018 ENSPF found that the institutional C-section rate in private facilities was 62.2%, markedly higher than 12.0% at public facilities.

Rates of C-section were influenced by key policies introduced in 2008 and 2012, such as removal of user fees, emergency transportation, quality improvement, and human resources for health training. The elimination of user fees for delivery care and C-section in 2008, and its extension to other obstetric complications in 2012 increased institutional delivery and C-section rates. Additionally, the introduction of free-of-charge emergency referral transport via the 2008 Acceleration Plan meant that more women could access emergency obstetric care in a timely manner. Quality improvements such as facility upgrades, better preparedness, and staff training also indirectly contributed to women seeking delivery care, especially for advanced procedures such as C-sections. Morocco’s emphasis on building cadres of specialist physicians, such as increasing the number of residency posts for obstetrician-gynecologists, has also helped to expand the availability of C-sections.