Key Takeaway: By decentralizing health services and strengthening the capacity of lower-level health care facilities, Senegal has made high-quality health care more logistically accessible to its citizens. This investment operates in tandem with efforts to eliminate financial barriers to care for the most crucial components of maternal and newborn health care.

Senegal has centered maternal and neonatal health in its public health agenda in recent decades, by prioritizing increased access to essential care as a nationwide priority. One interview respondent spoke to this, saying:

There have been proactive policies to lower costs, making access possible at a lower cost for most women

- Interview respondent

This section of the narrative briefly summarizes the health care system of Senegal for context, then highlights selected programs and policies that have been instrumental in reducing NMR and MMR in the country. A more complete policy timeline is included in the Milestones section.

Health system structure

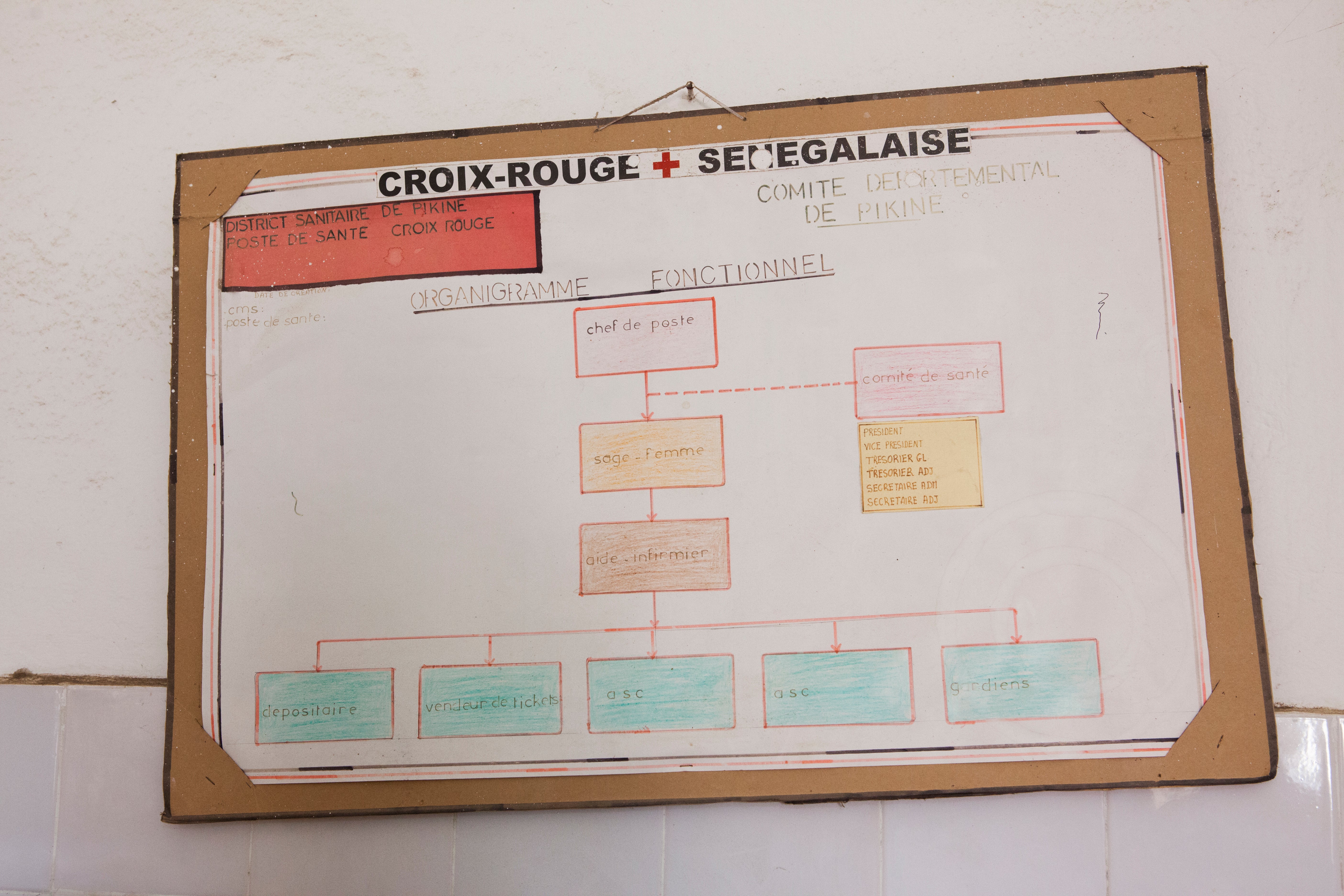

The health system of Senegal is organized into three main sectors: the public sector managed by the Ministry of Health and Social Action, the private sector, and the country’s armed forces. The majority of health care facilities across Senegal operate in the public sector—only a few health facilities are specific to the armed forces and 72% of the country’s private facilities are located in and around Dakar. The country’s health care system is structured like a pyramid, as shown in Figure 20. Hospitals operate at the national and regional level, health centers provide an intermediate level of care, and health posts—as well as health huts—work predominately at the community level. Lower-level health facilities are increasingly where women are choosing to give birth, as in 2019 60.8% of facility-based births occurred at public health posts.

Figure 21: Health System Structure in Senegal

Brunner B, Barnes J, Carmona A. Senegal Private Health Sector Assessment: Selected Health Products and Services. Strengthening Health Outcomes through the Private Sector Project. https://shopsplusproject.org/where-we-work/africa/senegal

Human resources for health

The expanding health infrastructure in Senegal was accompanied by a growing health workforce. From 2004 to 2019, the number of practicing nurses and midwives in Senegal grew from 3,287 to 8,807, while the number of doctors grew from 594 to 1,435., These gains outpaced overall population growth in the country, as the density of both nurses and midwives and doctors per 10,000 people increased slightly over the last two decades as shown in Figure 22., The growing number of health care providers can in part be tied to reinforced training programs that built on the national training plan for health personnel established in 1996. In 2002, the establishment of Regional Health Training Centers expanded the number of training programs for providers such as nurses and midwives. Accredited private training programs have followed, which offer a three-year training program to become a registered midwife. Similarly, in 2005 the training of doctors expanded beyond Dakar as Training and Research Units and private schools were established in several regions throughout Senegal.

Several policies have contributed to improvements in increased provider availability. These include the implementation of a contractualization policy in 2002 aimed at filling existing staffing gaps in the public sector; the creation of the human resources department in 2003 intended to standardize provider classifications and improve consistency of quality care; and the launch of the Cobra Plan in 2006, which was instituted to rapidly fill emergency staffing needs without usual administrative delays. These individual programs were supplemented by a National Plan for Human Resource for Health Development from 2011 to 2018 that streamlined administrative processes and health system monitoring while also focusing on improving health worker density in rural areas.

Figure 22: Healthcare Worker Density in Senegal from 2004 to 2019

WHO Global Health Workforce Statistics Database. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/health-workforce

Community health workers

In addition to doctors, nurses, and midwives, Senegal has a long history of involving community health workers. Today, Senegal’s estimated 25,000 community health workers are formally divided into five categories, with each serving a distinctive role in improving health outcomes throughout the country, especially in rural areas.,

Community-based health care workers are men and women selected by community members who receive structured training that enables them to provide basic preventive and curative services in health huts or assist nurses at health posts. These services often focus on family planning, maternal and child health, sanitation, hygiene, nutrition, tuberculosis, HIV, and sexually transmitted infections.

Dispensateurs de soins à domicile (“home health care providers”) are also community-elected representatives who work to extend the reach of the community health system from health huts into the home, primarily focusing on households beyond a reasonable commute from health huts.

Relais communautaires (“community liaisons”) are trained on techniques for behavior change and focus on communication, health promotion, and community mobilization. Training for this class of community health worker includes lessons about promoting high-priority maternal, neonatal, and child health interventions—and in recent years has included revitalized guidance about how to best communicate family planning messages.

Matrones are women who focus on maternal and reproductive health, often providing assistance to mothers during pregnancy. At health centers and health posts they often serve in a support role, while in health huts they may be the lead provider because they are trained to perform normal deliveries. In the absence of a midwife, matrones are responsible for delivery care, as one interview respondent spoke to:

The role of the matrones is also very important because normally they are trained to do unannounced deliveries in the health huts, but if you go to a very remote area when a woman has to give birth at night and she has no means of transport, it’s areas where there is no electricity, you need matrones in the huts to deliver them. They are trained for this, and they have all the equipment to make a safe delivery, to give the first essential care to the baby and then accompany the emergency evacuation of the woman to the nearest health post.

- Interview respondent

Bajenu Gox represent a unique Senegalese cadre of community health workers formally established in 2009 with the goal of reducing maternal and infant mortality. This class of community health workers is based on the traditional Senegalese social role of the Bajen (“paternal aunt”) who provides guidance and counseling in crisis situations. Generally older women selected from the community, the Bajenu Gox prioritize maternal and child health, raise awareness about health issues, and serve as an advocate for women’s health. They often work with the community at the level of health centers, neighborhoods, and villages, and cooperate with community leaders to raise awareness. Their involvement has contributed to improvements in the use of family planning, antenatal care, and postnatal care mainly through ensuring that women and girls have access to appropriate health care facilities. One interview respondent communicated the importance of Bajenu Gox and community health workers in general, saying:

I think that the Bajenu Gox came on top of a revolution that Senegal had launched since 1978 through primary health care, which was the participation of the population and the use of community health workers. I think it was a real revolution for Senegal, knowing our traditional system and our elitist medicine centered on the curative, the fact of using people and transferring competence to nonmedical agents and asking them to carry out activities at the level of villages and poor neighborhoods, it was a real revolution

- Interview respondent

To oversee this diverse workforce of community health workers and facilitate communication between community actors, in 2013 the Ministry of Health and Social Action established a community health unit. This was shortly followed by the National Community Health Policy (2014–2018) that sought to promote the participation of the Senegalese population in the health care system and coordinate community interventions across the country. The ultimate goal of this policy was to ensure universal access to high-quality, basic community health services—especially for mothers and newborns.

Midwife-led care

Senegal has made efforts to grow its workforce of female midwives, acknowledging that women often prefer being treated by other female providers, while also professionalizing the role by requiring three years of training to be registered.

In hospitals, midwives generally follow up on simpler cases and compile patients’ files, while at the health center and health post levels, midwives often perform and lead consultations. Midwife-led services may sometimes occur in cooperation with a nurse and can include the whole package of care including family planning, antenatal checkups, delivery of care, and postnatal consultations.

In 2014, the Ministry of Health and Community Action launched the Mobile Midwifery Strategy, which aimed to strengthen demand for antenatal consultation, improve access to high-quality care, and strengthen the oversight of community health workers.13 This cadre of mobile midwives, who spend most of their time working in health huts, community sites, and gathering places such as weekly markets, improves the availability of essential maternal and child health services.13 These outreach services have also been found to lessen the workload for staff at health posts, affording them more time to attend to patients in the facility itself.13

Between 2010 and 2018, the number of registered midwives increased from 1,005 to 2,677, all exclusively women., At a rural health post during this study, female patients said that having a midwife in the health post encouraged their attendance at the health facility. During this study, five facilities visited in the Saint-Louis region lacked nurses, and as such, maternal and newborn care were mostly carried out by a midwife. As a result, the “head nurse” title at health posts has been amended to “head of post,” opening up the position to midwives instead of exclusively nurses.

We realized that when we put a state nurse there was an overload of work which did not allow them to provide quality care and to function seven days a week, 24 hours a day. This is what led to the introduction of midwives wherever there was a maternity hospital.

- Interview respondent

National health and social development plans

Since its independence in 1960, Senegal has implemented a series of national health development plans. A key goal of the earlier development plans was to build one hospital per region. This was shortly followed by plans to construct health centers in each department, and later to expand the network of rural health posts.

From 1981 to 1998, regional development plans were introduced, before national health and social development plans were reintroduced in 1998. One interview respondent spoke to the importance of these plans, saying:

Senegal has a very good tradition of planning, but health planning with the national health development plan, especially the first one from 1998 to 2008, ... this plan was essential for Senegal because for the first time in our history, we structured in time the objectives that we want to achieve for at least five years.

- Interview respondent

Three 10-year plans have since been implemented, each with a slightly different focus but all giving priority to maternal and neonatal health. The first national health and social development plans from 1998 to 2007 included human resource reform, the construction and rehabilitation of health facilities, and a focus on reproductive health in the form of increased skilled birth attendance at delivery and emergency management. The creation of the Reproductive Health Division at the Ministry of Health and Social Action in 1998 helped advance the objectives of the first national health and social development plans. The second national health and social development plans from 2009 to 2018 sought to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality by repositioning family planning and ensuring better care for newborns during the neonatal period. The latest plan will span from 2019 to 2028 and focuses on progressing the country toward universal health coverage to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

Throughout the series of national health development plans, decentralization has been a common theme as the country has sought to make services available at lower-level facilities. These plans have achieved this by expanding physical infrastructure, bolstering the lower-level health workforce, and innovating strategies through which more complex care can be administered in more accessible settings.

National Free Delivery and Caesarean Policy

In an effort to improve health care utilization and mitigate barriers to care, Senegal implemented the National Free Delivery and Caesarean Policy in 2005, originally piloting the program in five regions considered to be among the poorest and to have the lowest access to care (Kolda, Ziguinchor, Tambacounda, Matam, and Fatick). Expanded to all regions besides Dakar in 2006, and later Dakar in 2012, the plan covered all normal deliveries at the health post and health center level as well as cesarean section (C-section) deliveries at the hospital level.

Facilities are remunerated for routine delivery services by the government via the dispersal of supply kits valued at US$11 including gauze, gloves, syringes, towels, vitamin K, antiseptics, and uterotonics. C-sections in hospitals were remunerated with US$110, while C-sections in health centers are remunerated with supply kits. In the five regions first impacted by this policy, the number of deliveries at health posts and health centers were 1.77 times higher in 2006 than in 2004, while other regions only saw utilization 1.19 times higher over this same time span. Women were also referred to higher levels of care more often, seeing a 49% increase in referrals from 2004 to 2005 when this policy was implemented. Additionally, the rate of C-section deliveries among in-facility births, which had previously been stagnant for years, saw a statistically significant increase from 4.2% in 2004 to 5.6% in 2005 in these five affected regions.

Our analysis of the Lives Saved Tool shows dramatic spikes in the number of lives saved via C-section and other facility-based interventions in 2005, suggesting that improved coverage of key interventions aligned with the enactment of this policy. A quantitative analysis of the impact of the National Free Delivery and Caesarean Policy in Senegal and similar policies in other African nations found that these programs not only led to higher health service utilization, but also contributed to reductions in neonatal mortality.

National Family Planning Action Plan

In 2012, nine francophone west African nations signed onto the Ouagadougou Call to Action in which delegations agreed to take concrete action on family planning and pledge unprecedented support of family planning. Propelled forward with this momentum, Senegal launched a National Family Planning Action Plan in 2012 that uses a framework referred to as the “3 D’s” of democratization, demedicalization, and decentralization. By expanding support for participatory family planning (democratization), removing policy barriers that prevent lower-level health care workers from providing basic family planning services (demedicalization), and strengthening community-level family planning programs (decentralization), Senegal has made rapid progress in expanding family planning services. This plan has also included widespread public awareness campaigns intended to erase stigma and a restructured supply chain strategy aimed at reducing stockouts of contraceptive products.

Under the new supply chain strategy, a professional logistician forecasts contraceptive supply and demand for facilities while a delivery team brings contraceptives to facilities. This approach—referred to as the “informed push” model—differs from the previous “pull” model in which providers themselves were expected to track and forecast contraceptive supplies at facilities. This approach was piloted for six months in the Pikine district of Dakar and eliminated stockouts of IUDs, implants, injectables, and pills. These commodities had respectively experienced stockouts at 14%, 86%, 57%, and 57% of facilities in the month before the pilot program. This approach has since been scaled up to the whole region of Dakar—reducing stockout rates to under 2% within six months—and was later scaled up nationally.

In 2019, met need for family planning using modern methods among married women reached 52.6%, which is a nearly 300% improvement since 1992 when met need was only 13.2%. Increased use of family planning in Senegal is reflected in the Lives Saved Tool analysis of maternal lives saved, as the impact of this intervention has increased in the last decade since the enactment of this policy.