A variety of factors contributed to India’s progress in reducing neonatal and maternal mortality rates. In this study, these interrelated factors were mapped to a conceptual framework with consolidated factors from existing evidence and frameworks that included categories of distal, intermediate, and proximate drivers, as shown below in Figure 5. In this section, progress on key proximate drivers is highlighted—especially with regard to intervention coverage spanning the continuum of maternal and newborn care, including preconception, antenatal care, delivery care, and postnatal care.

Figure 5: Conceptual framework for the drivers of maternal and neonatal mortality decline

As each indicator is discussed, progress is contextualized within India’s four major national health policy periods, shown below in Figure 6. More detailed descriptions of each of these policy periods can be found in the How did India Implement section of the .

Figure 6: India’s national-Level health policy periods

After reviewing trends in selected key maternal and newborn health (MNH) intervention coverage indicators, quantitative analyses are presented that link this progress to reductions in neonatal mortality rate (NMR) and maternal mortality ratio (MMR). These include an analysis that isolates the impact of fertility decline on mortality levels using Jain’s decomposition method as well as an analysis that calculates the fraction of neonatal mortality attributable to a variety of risk factors. While both of these analyses have specific limitations, each also offers unique insights. Together, this body of evidence tells a story about how proximate factors contributed to India’s reductions in neonatal and maternal mortality.

Fertility decline has contributed to mortality reductions, in part by influencing related risk factors

Declines in fertility in India’s lower mortality state cluster are related to trends in proximate factors—such as increased family planning coverage and age at marriage. Shifts in other intermediate and distal factors such as women’s education, employment, socioeconomic status, and other social determinants have also affected the country’s fertility rate. Defined as the number of children a woman would have if she were to experience the prevailing fertility rates at all ages and survived throughout her childbearing years, India’s total fertility rate declined from 3.2 to 2.1 births per woman nationally between 2000 and 2019. Total fertility levels in the lower mortality state cluster were below India’s nationally, at a total fertility rate of 2.4 births per woman in 2000 and 1.6 births per woman in 2019, as shown below in Figure 7. The lower mortality cluster Exemplar states had similar total fertility rates in 2019, at 1.6 births per woman in Maharashtra and 1.5 births per woman in Tamil Nadu.

Figure 7: Fertility trends in India’s lower mortality state cluster

Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Government of India. Sample Registration System Statistical Report 2019. New Delhi: Government of India, 2022. Accessed September 10, 2024. https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/44375/download/48046/SRS_STAT_2019.pdf

Shifts in the previously mentioned intermediate and distal factors have contributed to particular reductions in fertility rates among younger women and girls. Between India’s 1992–1993 NFHS and 2019–2021 NFHS, the age-specific fertility rate for women and girls ages 15 to 19 decreased 62.9% from 116 to 43 births per 1,000 woman-years., This decrease is mirrored in the lower mortality Exemplar states of Maharashtra and Rajasthan which respectively experienced reductions in age-specific fertility rates among women and girls ages 15 to 19 years of 66.7% and 60.9%.,

In addition to their impacts at the individual level, lower fertility rates also have consequences for the broader health system. The number of births each year in India has stayed relatively steady in recent decades, balanced by fertility decline and population momentum. These factors have created a landscape in which maternal and newborn health programs must focus on a relatively consistent number of annual births. This makes fertility decline a key factor in our study that is interconnected with several key proximate factors that underlie India’s trajectory of progress. Because birth risks are elevated for mothers of lower age and higher parity, fertility decline might also be associated with a shift in the age-parity distribution, reducing overall maternal and neonatal mortality risk.

Assessing fertility decline as a contributor to NMR/MMR reduction

India’s lower mortality state cluster has experienced substantial decreases in fertility—as noted above—with total fertility rate declining from 2.4 to 1.6 births per woman between 2000 and 2019. As described in Jain’s decomposition methodology, declines in fertility translate to fewer high-risk pregnancies by way of longer birth intervals and lower birth parity, as well as decreased birth rates, specifically among teen girls and older women. This analytical approach isolates the impact of fertility decline on neonatal and maternal mortality reduction.

Declines in fertility levels within the lower mortality state cluster were associated with 172,527 fewer neonatal deaths and 8,912 fewer maternal deaths in 2020 than would have been expected if fertility levels had remained constant since 2000. This decomposition approach attributes the remaining portion of mortality reductions to “safe motherhood” initiatives—interventions that target maternal and newborn health. Together, fertility decline and improved coverage of safe motherhood initiatives led to 400,194 neonatal lives and 2,217 maternal lives saved in 2020 compared to what would have been expected if fertility rate and intervention coverage levels had remained constant since 2000. This finding, shown below in Figure 8, highlights the impact of fertility decline as a key contextual factor related to NMR and MMR decline in India’s lower mortality state cluster, in tandem with other health care indicators commonly associated with mortality reductions.

Figure 8: Attribution of mortality reductions to fertility decline and improved intervention coverage in India’s lower mortality state cluster

Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Government of India. Sample Registration System Statistical Report 2019. New Delhi: Government of India, 2022. Accessed September 10, 2024. https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/44375/download/48046/SRS_STAT_2019.pdf

Improvements in proximate reproductive, maternal, and newborn health coverage indicators

The proximate MNH intervention coverage factors described in this section were found to most directly contribute to improved maternal and newborn health outcomes in India over recent decades and were in turn influenced by broader distal and intermediate factors in the framework. Throughout this section, we mention upstream intermediate and distal factors that fed into this progress, which are described in more depth in the and sections.

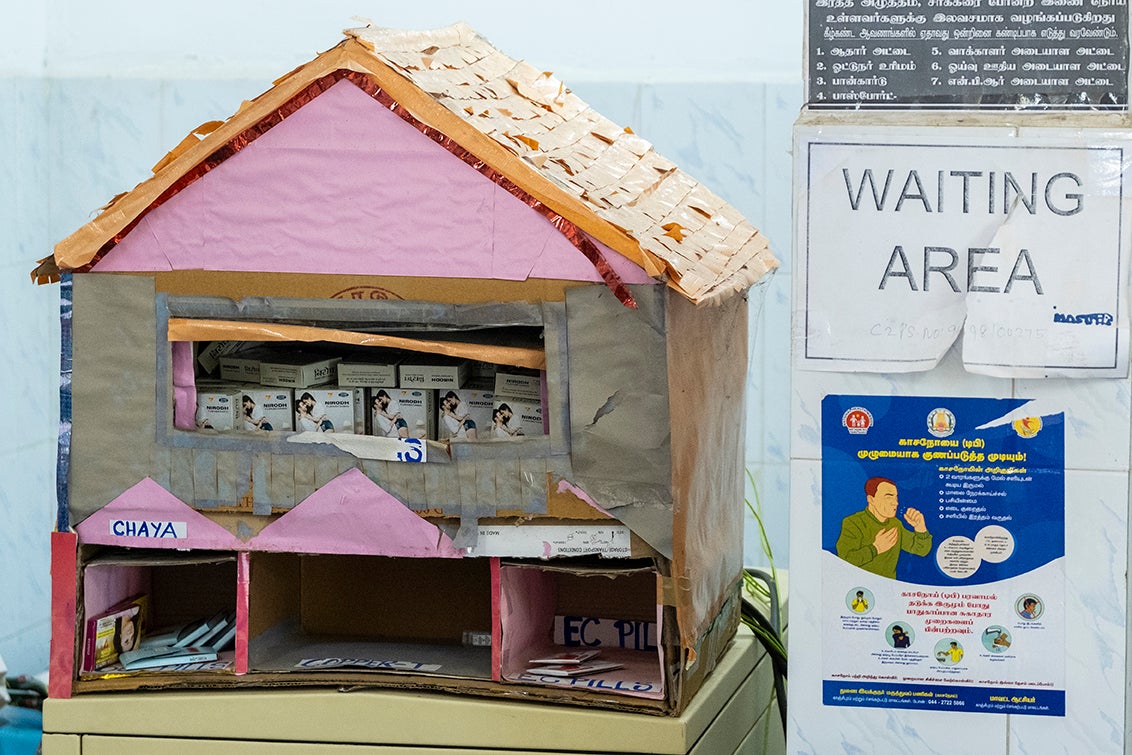

Contraception

Demand for family planning met using modern methods has increased in India nationally over recent decades and has also been higher in the lower mortality state cluster. As of India’s 2019–2021 NFHS, 83.9% of family planning demand nationally was satisfied using modern methods, which was higher in the lower mortality state cluster, at 90.3%. The lower mortality Exemplar states of Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu had even more demand satisfied using modern methods, at 96.1% and 95.3%, respectively, as shown below in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Family planning demand satisfied by modern methods in India’s lower mortality state cluster

Over the last several decades, family planning has been increasingly integrated into broader maternal health programming, as opposed to a separate focus area. This integration has contributed to upticks in demand satisfied in the NHM/RMNCH+A period, after a period of stagnation during the mid-2000s to mid-2010s. Although demand satisfied in the lower mortality state cluster is high, female sterilization remains the most common form of contraception utilized. As of the 2019–2021 NFHS, 63.8% of married women in Maharashtra reported using modern contraceptive methods, and female sterilization was the method employed for 77.0% of these women. Similarly, in Tamil Nadu, 65.5% of married women reported using modern contraceptive methods, and female sterilization was the method used for 88.2% of these women.

Antenatal care

India has seen rapid improvements in antenatal care (ANC) coverage, with 93.7% of pregnant mothers in 2018 receiving an antenatal care visit nationally as compared to 64.8% in 1989., The lower mortality state cluster has historically had higher coverage of ANC visits and in 2018, 96.7% of pregnant women received at least one antenatal care visit. The lower mortality Exemplar states of Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu had similarly high coverage, respectively at 96.8% and 97.0% in 2020, as shown below in Figure 10. Tamil Nadu has had high coverage for decades, whereas Maharashtra showed the most rapid progress during the RCH-I period from 1997 to 2005, overcoming minor setbacks in the previous years.

Progress in coverage of at least four antenatal care visits (ANC4+) was also most pronounced during the RCH-I period from 1997 to 2005. During this period, the lower mortality state cluster’s ANC4+ coverage improved at an average annual rate of change (AARC) of 3.5%, with ANC4+ increases in Maharashtra more than two times this pace, at an AARC of 7.9%.,, As of 2018, ANC4+ coverage in the lower mortality state cluster was 76.1%, compared to 58.6% nationally. In 2019, the lower mortality Exemplar states of Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu had ANC4+ coverage levels of 76.3% and 91.5%, respectively.

Tamil Nadu’s long history of high ANC coverage can be linked to the early implementation of the Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddy Maternity Benefit Scheme, launched in 1987. This program established financial incentives for women accessing government health care including ANC. Similar national-level conditional cash transfer programs such as the Janani Suraksha Yojana and Janani Shushu Suraksha Karyakaram initiatives were influenced by the design of this scheme. In the years before these national programs, Tamil Nadu’s early adoption of its state-specific policy positioned the state well for success.

Figure 10: Any antenatal care coverage trends in India’s lower mortality state cluster

India’s lower mortality state cluster has improved not only the coverage of ANC, but also the quality of this care. To approximate quality of ANC, we employed an index that included nine components that generally reflect whether ANC was administered in a timely manner by a skilled provider who conducted key screenings, tests, and examinations as appropriate—collectively representing a maximum score of 13 points. Using that index, high-quality ANC (ANCq) was defined as ANC that satisfied at least 9 of the 13 points. Between 1996 and 2018, the percentage of pregnant women in the lower mortality state cluster who received high-quality ANC increased from 59.2% to 94.2%.,, In the lower mortality Exemplar states of Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, high-quality ANC coverage respectively improved from 62.9% to 94.4% and 78.6% to 96.0% between 1996 and 2019.,, Across the lower mortality state cluster, and especially in Maharashtra, the high-quality ANC coverage improved most rapidly during the RCH-II/NRHM period from 2005 to 2012.

Institutional delivery

The central government emphasized the importance of institutional delivery during the RCH-II/NRHM policy period from 2005 to 2012. The Accredited Social Health Activists program and the Janani Suraksha Yojana scheme helped to generate demand for institutional delivery by engaging with communities and offering financial incentives for care-seeking behavior. In addition to these national programs, lower mortality Exemplar states implemented initiatives that also contributed to advancements.

For example, Maharashtra’s 1997 Matrutwa Anudan Yojana scheme included financial incentives for marginalized women in high-risk districts who accessed pregnancy and delivery care. In 2005, Maharashtra also became one of the first Indian states to adopt a strategy of task-shifting to ayurveda, yoga and naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and homeopathy practitioners to identify high-risk pregnancies and refer mothers to higher-level facilities as necessary.

Tamil Nadu also implemented policies meant to increase institutional delivery rates and alleviate concerns and fears women might have about delivering in health facilities. For example, the 2004 birth companionship policy ensured all pregnant mothers would be able to bring one friend or relative with them throughout health facilities to support them through the delivery process. Tamil Nadu also implemented a policy in 2011 that provided a free hearse service for women who died in facilities during delivery—noticing that some families were leaving facilities in cases of emergency for fear of the financial cost of dying in a health facility.

These state-specific policies complemented national-level programming to spur a major increase in institutional delivery. In Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, the institutional delivery rates were respectively 41.8% and 60.0% in 1989. By 2019, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu respectively had institutional delivery rates of 97.3% and 99.8%, as shown below in Figure 11. These coverage levels are slightly higher than the national institutional delivery rate of 89.9% in 2018. Across most of the lower mortality state cluster, progress was most rapid during the RCH-II/NRHM policy period from 2005 to 2012.

Figure 11: Institutional delivery trends in India’s lower mortality state cluster

In the lower mortality state cluster, a relatively higher portion of institutional deliveries occurred in public and private hospitals compared to lower-level facilities. As of the 2019–2021 NFHS, 37.8% of institutional deliveries in Maharashtra and 47.1% of institutional deliveries in Tamil Nadu took place in public hospitals. An additional 43.0% and 34.7% of institutional deliveries in each respective state took place in private hospitals. In contrast, less than half of institutional deliveries in the higher mortality Exemplar states took place in hospitals.

The lower mortality Exemplar states have sought to promote institutional deliveries in higher-level facilities, which should have more capacity for managing complications and providing emergency care, while also continuing to improve quality of care in these facilities. For example, Maharashtra’s unique LaQshya-Manyata initiative has adapted quality standards for public facilities to private hospitals. These standards have added weight to the accreditation process, promoting better quality maternal care in private health facilities. Quality improvement has been rooted in rigorous maternal death audits, which in Maharashtra recently expanded to include near-miss audits as well.

Cesarean section

Higher institutional delivery rates across the lower mortality state cluster contributed to increases in cesarean section (C-section) rates; the increases are shown below in Figure 12. From 1990 to 2018, India’s C-section rate rose nationally from 2.4% to 22.4%, and the C-section rate in the lower mortality state cluster grew from 4.3% to 34.5%., In particular, rising institutional C-section rates in public hospitals help spur overall C-section rates in the lower mortality state cluster. As of the 2019–2021 NFHS, the C-section rate at public facilities in the lower mortality state cluster was 29% as compared to 14% in the higher mortality state cluster.

In 2019, the C-section rates in Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu were 32.3% and 48.7%, respectively. Although progress in improving C-section rates is a key contributor to reductions in NMR and MMR, these relatively high C-section rates suggest that the procedure might increasingly be used when it is not medically necessary.

Figure 12: C-section trends in India’s lower mortality state cluster

Postnatal care

Nationally, coverage of postnatal care for the woman or baby increased from 13.4% to 82.8% between the 1998–1999 NFHS and 2019–2021 NFHS., This percentage was slightly higher in the lower mortality state cluster in the 2019–2021 NFHS at 87.0%, as shown below in Figure 13. The lower mortality Exemplar states had even higher postnatal care coverage in this survey, at 87.4% in Maharashtra and 94.4% in Tamil Nadu. Increases in postnatal care coverage can also be attributed to the expanded role Accredited Social Health Activists play in providing home-based newborn care.

Figure 13: Postnatal care coverage trends in India’s lower mortality state cluster

Disaggregating risk factors for neonatal mortality yields insights into socioeconomic and demographic groups that have experienced rapid progress

Increased coverage of proximate interventions and shifts in contextual factors like fertility are linked to India’s NMR and MMR reductions. Studying disaggregated neonatal mortality trends can also shed light on how equity gaps between socioeconomic and demographic groups have closed—and contributed to overall progress. By assessing relative risks and the prevalence of risk factors over time, we can assess where and for whom India’s lower mortality state cluster has been most successful in reducing NMR. These insights can shed light into which populations have experienced the most rapid progress, and which risk factors have been key in driving progress.

Through this analysis, we can calculate a population attributable fraction (PAF) for a series of factors, representing the proportion of neonatal mortality attributable to each risk factor. Trends in PAFs over time can be linked to both a change in the relative risk of that factor and a change in the composition of that factor. Linking back to this study’s conceptual framework, the factors considered in this analysis comprise proximate indicators mentioned earlier such as ANCq coverage and place of delivery, contextual factors related to fertility such as age at birth, previous birth interval, and birth order, as well as individual assessments of intermediate and distal factors such as urbanicity, wealth, and education.

In the 2005–2006 NFHS, the factors with the highest levels of attributable neonatal mortality in the lower mortality state cluster were identified as residence in a rural area (30.5% of neonatal deaths), low household wealth (27.8% of neonatal deaths), short birth interval (25.4% of neonatal deaths), and maternal age of under 20 years (13.2% of neonatal deaths). Births in these categories were respectively found to be 1.7, 2.0, 1.4, and 1.7 times more likely to result in neonatal mortality.

Between the 2005–2006 NFHS and the 2019–2021 NFHS, the PAFs for several of these factors experienced substantial declines. For example, the PAF for residence in a rural area decreased from 30.5% to 18.0% of neonatal deaths., This reduction aligns with the narrowing gap between NMR in rural and urban areas in the lower mortality state cluster because NMR in rural areas declined at an AARC of -4.7% between the 2005–2006 NFHS and 2019–2021 NFHS, whereas NMR in urban areas declined at an AARC of -3.2%., Over time the percentage of the population living in rural areas remained relatively constant, decreasing only slightly from 65.1% to 63.2%.,

Similarly, the PAF for low household wealth decreased from 27.8% to 15.6%., NMR reductions in the poorest tertile (third) occurred at a similar pace as the wealthiest tertile, but over time fewer residents in the lower mortality state cluster were considered to be in the poorest tertile as defined by the wealth thresholds used in 2005–2006 NFHS survey. Although 38.6% of households were considered part of the poorest tertile in the 2005–2006 NFHS, by the 2019–2021 NFHS, only 18.9% of households remained poorer than that same wealth threshold.,

Together, the trends in rural residence and low household wealth highlight that PAFs might decrease as a result of either a reduction in risk for that category—as in the case for rural residence—or a decreased percentage of the population in that category—as in the case for low household wealth. In each case, reduction of the overall PAF has contributed toward the lower mortality state cluster’s progress in reducing the burden of neonatal mortality linked to residence or wealth status.

Other factors more proximately related to maternal care, such as antenatal care and institutional delivery, were also considered through this analysis. Because coverage of antenatal care and institutional delivery are generally higher in the lower mortality state cluster, a relatively smaller portion of neonatal deaths in the lower mortality state cluster are attributable to a lack of these key maternal health services. The percentage of neonatal deaths attributable to lack of institutional delivery decreased from 8.2% to 3.6% between the 2005–2006 NFHS and 2019–2021 NFHS, as shown below in Figure 14.,

Overall, this analysis highlights that narrowing wealth gaps, declines in fertility, improvements in female education, and provision of key maternal health services such as institutional delivery are associated with declines in neonatal mortality over time. Although these factors are interrelated, this analysis nonetheless sheds light on the effect of various intermediate and proximal factors on mortality reduction in India’s lower mortality state cluster.

Select factors within this analysis should be interpreted with caution because differences in neonatal mortality were not statistically significant between groups. NMR between the Hindu and non-Hindu groups was not found to be statistically significant in either the 2005–2006 NFHS or the 2019–2021 NFHS. Other factors—caste, ANC, and high-quality ANC—did not show statistically significant differences in NMR for the baseline 2005–2006 NFHS, but did for the endline 2019–2021 NFHS, limiting the interpretability of trends over time between the two surveys.