In Ghana, Exemplars research identified two ways, or pathways, through which reforms have improved PHC outcomes. The first pathway enabled health system efficiency at the national, regional, and local levels by ensuring increased resources for the health system; establishing decentralized, data-driven processes for planning and decision making; and coordinating with development partners on the management and use of funds.

Key Points

Ghana is a relatively young democracy: in 1992, it held its first free elections in more than a decade. Since then, the country’s two main parties—the National Democratic Congress and the New Patriotic Party—have treated health policy as a key electoral issue. Many key reforms, such as the adoption of a National Health Insurance Scheme via abolishing the “cash-and-carry” user fee system and the widespread implementation of the Community-Based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) system, began as campaign issues.

During the Exemplars study period from 2000 to 2018, Ghana implemented a series of health system reforms that aimed to improve the availability and flow of health funding, increase health workers’ productivity, and replace top-down planning practices with policies that encouraged shared decision making.

Ghana increased autonomy at the district and facility levels of the health system, giving local authorities more power to make critical planning and budget decisions.

Ghana introduced mechanisms for coordinating the support of external donors and development partners, such as sector-wide approaches and donor pooled funds. These reforms increased the efficiency of the health system by aligning resources around a single set of priorities.

Using implementation research and evidence gathered from health data systems, Ghana shaped and supported PHC reforms. For example, this Exemplars research has been a key part of the CHPS’s transition from pilot to policy.

PHC reform in Ghana: a bipartisan priority

Since 1992, Ghana has been a democracy in which two main political parties—the National Democratic Congress and the New Patriotic Party—compete for votes, in part by responding to popular demands for important social services like PHC.

Ghana’s economy has also grown very quickly since 2000, especially after energy companies discovered the offshore Jubilee oil field in the South Atlantic Ocean in 2007. In 1995, the World Bank classified Ghana as a low-income country. In 2024, it is a lower-middle-income country with the second largest economy in West Africa., Yet in spite of this economic growth, Ghana’s poverty rate has remained high: almost one-quarter of the population was poor in 2017. The need for social services continues to be significant and salient political issue.

Health policy in particular has become a key electoral issue, and policymakers across the political spectrum include clear statements of goals for reforming the health system in party platforms and campaign materials. For instance, New Patriotic Party politicians campaigned for the 2000 election on a promise to abolish the widely despised “cash-and-carry” user fee system, and when they came to power, they introduced the National Health Insurance Scheme. Similarly, reform of the National Health Insurance Scheme and the widespread implementation of the CHPS system were campaign promises in the tense 2008 election, which the National Democratic Congress narrowly won.

This bipartisan commitment to improving PHC coverage and outcomes has enabled Ghana to implement innovations aimed at expanding financial and geographic access to key PHC services. It also helped ensure the steady flow of resources that made the health system more efficient and equitable during the Exemplars study period.

Sharing authority and responsibility for decision making

The of post-colonial Ghana has been tumultuous, and the country’s democratization has not always proceeded in a straight line. However, from Ghana’s independence in 1957, officials have consistently adopted political reforms that seek to reduce the size and responsibility of the central government and boost the authority of regional and local decision-making bodies.

Ghanaian policymakers have often envisioned decentralization and local institution-building as key parts of the day-to-day practice of post-colonial citizenship., Ghana’s 1992 constitution, which transitioned the country back to democracy from military rule, embodies this way of thinking. It requires the central government to “make democracy a reality by decentralizing the administrative and financial machinery of government to the regions and districts and by affording all possible opportunities to the people to participate in decision making at every level in national life and in government.”

Financing decentralization: District Assemblies and the District Assemblies Common Fund

In 1988, the Provisional National Defense Council military dictatorship, in power at that time in Ghana, introduced the Local Government Law, which established District Assemblies with some elected members. In 1991, Ghana began its transition back to civilian rule, and the new constitution approved by voters in 1992 maintained the District Assembly system.

The next year, Ghana’s national government established the District Assembly Common Fund to allocate “not less than 5% of tax revenues of Ghana” to the District Assemblies to spend on local programs and priorities including infrastructure, poverty reduction programs, education, and health care. The District Assembly Common Fund distributes this money to each assembly according to a formula that accounts for variables such as local poverty levels, unmet needs, and assemblies’ ability to raise funding from other sources.

This guaranteed, reliable source of revenue from the national government has made it possible for districts across Ghana to undertake key infrastructure and other local development projects, make consistent plans for the future, and respond to local priorities that might otherwise be ignored.

In the health sector, decentralization typically aims to make service delivery more efficient, effective, and responsive by tailoring it to local needs. It also seeks to improve access to health services, particularly in poor or rural areas the system has not always comprehensively or adequately served.

Ghana’s efforts to strengthen managerial and administrative capacity at every level of the health system, engage citizens in decision making, and promote accountability in the management of health resources enable the implementation of other key initiatives such as the National Health Insurance Scheme and CHPS.

The process of health system decentralization in Ghana had two main components: (1) administrative decentralization for governance and service delivery and (2) fiscal decentralization for planning and budgeting.

Administrative decentralization

As part of Ghana’s efforts to build a more efficient, equitable, and locally accountable health sector, the Ghana Health Service (GHS) and Teaching Hospital Act of 1996 aimed to transfer authority for the health system from the Ministry of Health (MOH) to a new, semiautonomous GHS, which was fully launched in 2003. The GHS is now responsible for all health service delivery in the public sector, including the delivery of PHC services, at the regional, district, subdistrict, and community levels nationwide. It maintains authority over 10 Regional Health Administrations and 110 District Health Administrations.

- Regional Health Administrations and District Health Administrations supervise and support service delivery in regions and districts.

- District Health Management Teams manage service delivery. Their leaders, District Directors of Health Services, are responsible for implementing health policies, monitoring their execution, and evaluating their success.

Overall, Exemplars primary data collection showed that districts demonstrate the highest degree of decision-making authority for the dimensions of health sector planning, procurement, and to a lesser degree – financial management. However, they have low decision-making authority for human resources, in terms of recruitment, hiring/firing, and remunerating core publicly funded health staff, despite that the recruitment and deployment of support staff is at the discretion of districts. Districts also reported low autonomy for service delivery, since the establishment of service packages and service models are defined at the central level, although districts and facilities can determine their relative focus on services according to the needs of the community (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Ghana district health directorate decision space

Fiscal decentralization

Districts in Ghana self-reported a high degree of autonomy in regard to financial management. The GHS has designated some 500 Regional Health Administrations, District Health Administrations, and regional, district, and subdistrict hospitals and health facilities as budget management centers. Budget management centers are authorized to formulate annual plans for spending the revenues the MOH allocates from the District Assemblies Common Fund and the funding that comes from other sources. Districts designated as budget management centers also have their own bank accounts and are authorized to incur expenditures locally, with discretion. Most of the district budget allocations comprise a mix of centrally incurred expenditure on behalf of districts, in addition to cash disbursements that enable local expenditures. Central expenditures are typically incurred for the three largest cost categories—such as human resources, drugs and commodities, and capital expenditure—and cash disbursements tend to reflect minority amounts of the district allocations. In addition to the district-approved health budgets, districts may also tap into the District Assemblies Common Fund to access additional funds. When there are shortfalls, districts may turn to development partners for assistance.

At the facility level, facilities have discretion over the internally generated funds that come from health insurance reimbursements and patient charges—although much of that is reserved for medicines to avoid stockouts, making 12.6% to 27% of total district cash budgets discretionary. To improve stockouts, the government recently began negotiating prices centrally, which enables facilities to purchase medicines from the regional medicine store at the negotiated, lower prices.

The autonomy granted to districts as a result of decentralization reforms has led to increased decisional authority, giving districts the ability to allocate and calibrate public health and primary health care resources according to community and local need.

Aligning government and partner resources

In Ghana, as elsewhere, donors and development partners have traditionally supported distinct and sometimes parallel health sector programming—often for family planning, maternal and child health, and HIV/AIDS. In Ghana, donor aid to the health sector, also known as development assistance for health, fluctuated during the Exemplars study period, but most years it comprised 15% to 20% of total health spending. Between 1995 and 2010 in particular, the number of donors to Ghana’s health sector proliferated, but they typically funneled aid into specific projects and disease control objectives such as diarrheal diseases, immunization, and maternal health.

Over time, this fragmented approach to health funding created two separate systems, government and donor-led, for decision making, supply procurement, resource allocation, and information management. At the same time, it channeled key funds away from the government’s own priorities for the health system—and especially from the delivery of PHC services.

Even before the Exemplars study period began in 2000, Ghana had started to experiment with mechanisms for donor coordination that would align development partners’ priorities with those of the health system. According to key informant interviews, the MOH and the GHS adapted these mechanisms to enable them to better support the country’s PHC system.

Sector-wide approaches and donor coordination

Sector-wide approaches (SWAps) are coordination mechanisms that bring together governments, donors, and related stakeholders to carry out joint planning, financing, monitoring, and oversight of countries’ health programs. SWAps may or may not include pooled funding instruments, but they maintain government ownership of health system priorities and key functions—including the development of budgets and plans, the facilitation of policy dialogue, and general oversight via monitoring and evaluation of health programs. SWAps aim to boost management capacity and enable overall improvements in system performance and efficiency.

In 1997, Ghana became one of the first countries to implement a SWAp to coordinate donor support, promote collaboration between development partners and government agencies, and improve the effectiveness of aid in the health sector., Its goal was to replace individual donor projects and parallel systems with a program of interventions aligned with the health system’s own structures and priorities. Most important, it aimed to channel donor funding through preexisting district and local infrastructures to improve the close-to-home delivery of key health services nationwide.

This first SWAp was established at the same time as Ghana’s first five-year program of work (1997–2001), and it had two parts: financing and management.

- Financing: The SWAp established the Health Fund, a large pool of money from donor agencies including the World Bank, the UK Foreign Commonwealth & Development Office (later known as the Department for International Development), and the Danish International Development Agency.

- Management: The SWAp established a common management arrangement, or a set of implementation practices for all parties to ensure they used the pooled fund and other resources in a way that aligned with national priorities for the health sector. The common management arrangement set the terms for MOH/GHS–donor collaboration across planning, oversight, and funding, and dictated rules for implementation, procurement, financial reporting, monitoring, evaluation, and sector review.

This first SWAp aimed to address system-wide priorities by channeling an increasing proportion of donor money through the Health Fund, which was administered by the MOH/GHS and directed flexible funds from development partners to budget management centers at the district and local levels where key health services were delivered., In this way, the pooled funding component of Ghana’s SWAp also sought to enable health system decentralization by providing district health managers with a pool of revenue they could spend at their discretion.,

The next five-year program of work (2002–2006) renewed Ghana’s health system SWAp. In 2004, Ghana’s MOH established a new donor pooled fund for the implementation of the country’s health sector priorities—including the National Health Insurance Scheme, the CHPS program, and the provision of essential medicines and medical supplies—using resources from multiple sources, including development partners. The GHS managed this donor pooled fund in partnership with the MOH and development partners.

The donor pooled fund coordinated and aligned health sector resources, especially at the district level, enabling more effective and efficient management and promoting greater transparency and accountability in resource management in the health sector. It also established a comprehensive financial management system (the Ghana Integrated Financial Management Information System) that was audited on a regular basis to ensure that funds were used in accordance with national policies and priorities.

In 2002, Ghana finalized its first national poverty reduction strategy to generate growth, control inflation, and increase spending on programs targeting the poorest Ghanaians. It brought new donor funding mechanisms to support the health sector, such as multi-donor budget support for bridging health equity gaps and improving service delivery efficiency.

Subsequent financing strategies likewise emphasized donor coordination and alignment with government policy. For example, the Health Sector Working Group encouraged coordinated dialogue between the donors and regular meetings with the government.

However, donors began to move funds from the pool managed by the MOH/GHS to the sector budget mechanism overseen by the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning. This was to ensure that funds were captured in the national budget. The shift reflected global trends in aid development toward accountability driven by ministries of finance, but the added bureaucratic layer resulted in delayed disbursement of funds.

Technically, Ghana's SWAp no longer exists, but the institutional capacity it built remains. Public officials have taken over many of its core financial and managerial functions. They oversee the alignment of funds from all sources and implement policies and programs that meet the priorities of the health system.

Likewise, donor pooled funds were discontinued with the SWAp, though the structures they put in place were retained. For instance, because the donor pooled fund was a major source of funding to districts, it increased the autonomy, adaptability, and capacity of district managers.

District donor coordination

Key informants reported that the level of coordination of donor activities with the district health system varied across functions and between study districts (Figure 9). For example, key informants from Jaman South and Zabzugu districts, both with efficiency scores of about 98%, reported a higher degree of government–donor integration. One Jaman South informant said:

"We have District Health Management Teams meetings every month. We also attend district assembly meetings. That is where sometimes we put in some of our proposals, and they are honored. And sometimes we write proposals to the MPs [members of parliament], and sometimes to the international level. The Japanese embassy supported us with a beautiful clinic."

More broadly, Exemplars subnational research depicted that across the four study districts, priority setting was the most widely adopted area for coordination, followed by health program monitoring and evaluation and financing (pooled funding). Degree of integration reported was the lowest for health commodity procurement and human resources. Figure 10 describes the range of coordination, with five being the highest degree of donor coordination, and one as the lowest.

Figure 10: District donor coordination mechanisms

Integration of vertical disease programs

Within country health systems, vertical programs typically focus on a single disease or condition. They often have their own staff, funding, and facilities, and they manage their own human resources, policy implementation, and data reporting and evaluation., Consequently, they can be expensive and inefficient—their fragmented activities can parallel or duplicate one another, and they can exist outside the control of national and local health authorities.

As part of Ghana’s donor coordination efforts, health officials worked with development partners and other stakeholders to integrate these vertical disease programs into the broader PHC system. For instance, since 2003, the HIV programs supported by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria have been integrated into the MOH’s National AIDS Control Program, National Tuberculosis Program, and National Malaria Control Program. The MOH is responsible for making policy, monitoring and evaluating the programs’ implementation, mobilizing resources, and regulating health service delivery, and the GHS is the main service provider. Development partners work with health officials to coordinate funding and strategic planning.

The goal of this approach is to reduce duplication in key health system functions such as supply chains, monitoring and evaluation, and service delivery, and to improve the quality and sustainability of health programs. The integration of specific disease programs into the health system likely helped stabilize Ghana’s HIV epidemic and make progress on the health-related Millennium Development Goals. It also coincided with an increase in tuberculosis treatment success rates and skilled birth attendance.

Figure 11: Ghana HIV and TB incidence rates

Using research and evidence to shape health policy

During the Exemplars study period, the MOH and GHS used evidence and information gathered from routine data systems and implementation research to support PHC reforms nationwide. This data enables officials to begin to close gaps between theory and practice, identify the policies that improve outcomes, prevent the inefficient use of resources, and allocate resources to meet local needs.

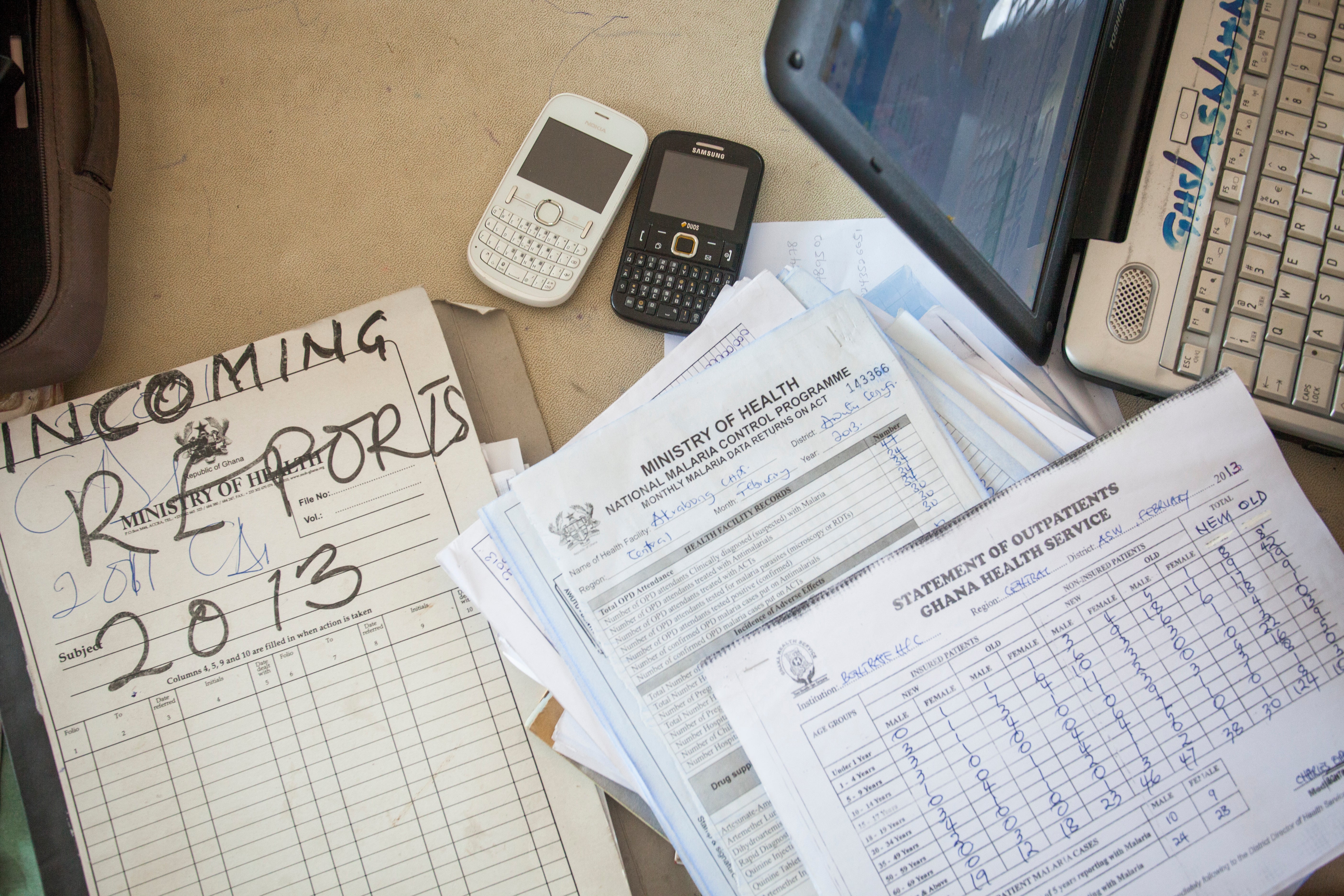

District Health Information Management System for data collection

Before 2012, officials captured health data using computer spreadsheets and paper-based information systems, a tedious, time-consuming, and incomprehensive process. Since then, Ghana has moved toward digitizing its health information infrastructure with the use of the open-source, web-based, interoperable District Health Information Management System 2 (DHIMS2)—a clustered system for Ghana that leverages the open-source District Health Information System 2 (DHIS2)—to gather, share, and use health-related data nationwide.,

Adopted to further Ghana’s decentralization efforts, DHIMS2 has made it easier to capture and share information and integrate health service operations. The system is the primary information source tracking the country’s health care delivery performance at every level: community, district, regional, and national. At the PHC level, community health workers record information covering vaccines, number of deliveries, family planning, antenatal services provided, and referrals. They also keep track of confirmed diseases, including malaria, cholera, and pneumonia. This data has enabled surveillance of potential disease outbreaks and identified gaps in care.

To encourage adoption and improve ease of use, the GHS piloted an e-Tracker mobile DHIMS2 device in 2015., Research indicates that workers who used it were able to more easily practice data management tasks, such as scheduling and tracking patient progress, and were more knowledgeable about data management.

By the end of 2016, four years after its launch, more than 90% of health service delivery facilities in Ghana were reported to be on the DHIMS2 platform. In 2021, about 85% of health facilities reported their data on time, and 95% of health facilities reported complete data to DHIMS2.

The GHS tracks its work with several other systems. These include the Ghana Integrated Financial Management Information System for financial data from hospitals and health centers and the Ghana Integrated Logistics Management Operation System for information on supply chains. The Centre for Health Information Management collects and reports health data across agencies.

National agenda for health research

Policymakers in Ghana have long relied on implementation research, which tests the way policies, programs, interventions, and reforms work in pilot or real-world settings, to shape and scale PHC programs., Research projects are often followed by new projects to monitor and guide the further implementation of lessons learned. This kind of research is especially important in decentralized countries like? Ghana, where policies and programs are not always implemented in the same way across different zones and districts.

For example, in 1996, District Health Management Teams, District Assemblies, and community members in Dangme, a poor rural district outside Accra, conducted a research project to test the feasibility of a health benefit package in the district. This research informed the development of the 2003 Ghana National Health Insurance Scheme.,

Around the same time, the Navrongo Health Research Centre conducted an experiment to test the impact of deploying trained community health nurses, volunteers, and culturally sensitive health and family planning services on fertility and childhood mortality rates in a district in Ghana’s rural north. This Navrongo experiment in “community-based health planning and services” was tested in other parts of the country and was eventually scaled nationwide—forming the basis for the CHPS program.

Read more about the Navrongo experiment and CHPS interventions here.