In Ghana, Exemplars research identified two ways (or pathways) through which reforms have over time improved primary health care (PHC) outcomes. The second pathway enabled more equitable access to quality PHC services by making PHC services more affordable, delivering PHC services to people in the communities where they live, and engaging communities themselves in health service delivery and oversight.

Key Points

Ghana decreased financial barriers to accessing care by experimenting with community-based health insurance schemes, which transitioned into a universal National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in 2003. The goal of the NHIS is to eliminate out-of-pocket payments and guarantee access to basic health services nationwide.

Since the beginning of the Exemplars study period (2000 to 2018), an approach known as Community-Based Health Planning and Services (CHPS)—a combination of community-based health workers, volunteers, and local outreach activities—has been the centerpiece of Ghana’s efforts to reduce health inequalities, eliminate geographical barriers to care, and bring primary health care (PHC) services to people nationwide.

Ghana has also implemented reforms aimed at mobilizing community participation and engaging community members in health system administration and oversight, decision making, and service delivery. In turn, these activities make service delivery more locally driven and led, which boosts PHC service utilization.

Making primary health care affordable to all

Figure 12: Evolution of Ghana health financing for PHC

When Ghana declared its independence from Great Britain in 1957, one of the main goals of the Convention People’s Party, according to prime minister Kwame Nkrumah, was to “arrange our national life according to the interests of our people” and “alter considerably the direction of the market processes” that had shaped governance in the Gold Coast colony under British rule. In particular, this meant finding a way for the government to provide key social services, including health care, to all Ghanaians.

They were starting largely from scratch; for instance, in 1957 just one-third of Ghana’s population lived within one hour of a health facility. The Convention People’s Party invested in hospitals and training programs, so that by 1967 the number of hospital beds doubled to 13,500 and doctors quadrupled to 1,100.2 It also provided free health services to everyone who used public hospitals, clinics, and other public sector facilities.,

However, by the early 1970s, a coup led by the police, armed services, and civil services had established a new government and replaced “free health care for all” with a system of user fees for some health services. In 1985, as part of the structural adjustment required by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank in exchange for loans, Ghana’s government implemented a new system called “cash-and-carry,” in which users had to pay for health services in Ministry of Health (MOH) facilities before they could receive them., Because fewer people could afford to pay for health services, the cash-and-carry system did ease some shortages of medications and supplies. However, studies showed that it prevented poorer Ghanaians from accessing essential care.

Grassroots self-help groups

To reduce these financial barriers to access, community-based organizations stepped in. In the 1990s, the Catholic Church established two Community-Based Health Insurance Schemes (CBHIS), one administered by a hospital in Nkoranza in North Ghana and one in Damongo in the Savannah Region. By 2000, the Nkoranza scheme covered nearly 30% of the people who lived in the district.,

Other churches and community groups nationwide followed the CBHIS’s example and established mutual health organizations that flourished with the support of external donors., Members of these organizations had broadened access to (and community ownership of) health care that was much more affordable. However, in exchange for the low premiums members paid, the mutual health organizations often covered very few services., They also did not cover many people: in 2002, Ghana’s 140 mutual health organizations covered about 2% of the country’s population.

National Health Insurance Scheme

The unpopularity of the cash-and-carry system, and the success of the CBHIS and mutual health organizations in the places where they existed, encouraged the government of Ghana to adopt a new system in 2003. The National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) aimed to eliminate out-of-pocket payments, increase the accessibility of health services, and encourage more people to use them. At first, the NHIS operated semiautonomous mutual health insurance schemes in districts nationwide, but starting in 2012 these schemes were combined into one National Health Insurance Authority.

The NHIS has four main sources of financing:

- The National Health Insurance Levy, a 2.5% value-added tax on goods and services (70% of the NHIS’s funding)

- Social security taxes collected from workers in the formal sector (23%)

- Individual premiums (5%)

- Funds from development partners and other sources (2%)

According to the NHIS, its benefits package covers 95% of diseases affecting Ghanaians and includes most outpatient and inpatient services, dental care, emergency care, maternity care, and all drugs on the NHIS’s approved medications list. It excludes some surgeries, most cancer treatments, organ transplants, and expensive drugs such as antiretrovirals for HIV (which are heavily subsidized by the separate National AIDS Program) (Figure 12). There are no copayments or deductibles.

National interview respondents indicated a broad range of services covered by the NHIS and linkages between NHI reforms and improvements in access. For example, one key informant said:

"For active members … you can walk in, and they will accept your card and produce services within the benefit of the scheme. You know the scheme reportedly covers about 95% of disease conditions affecting the people of Ghana…. Even breast cancer is covered."

In theory, all Ghanaians are required to enroll in the NHIS or another insurance scheme. Although this requirement is not enforced, enrollment does continue to climb. In 2019, the World Health Organization reported that a little more than one-third of Ghanaians were NHIS members, but by 2022 official statistics counted 16 million members, or 54% of Ghana’s citizens.,

According to the 2021 census, when private insurance is factored in, 68.6% of the population had some form of health coverage. In the four study districts, health insurance coverage (including both private and NHIS insurance) ranged from 61% to 91%.

Figure 14: Health insurance enrollment by district

Read more about challenges associated with NHIS enrollment here.

Studies indicate that the NHIS improved access to PHC among some users, and has improved the affordability of health services because people no longer pay for those services at the point of use. It has also provided financial risk protection, improved service delivery in some facilities,, and boosted utilization of services such as maternal care services. For instance, a study from 2003–2007 found that NHIS-insured pregnant women were more likely to receive prenatal care (85.7% versus 72%), deliver at a hospital (75% versus 52.9%), have deliveries attended by trained health professionals (65.7% versus 46.6%), and experience fewer birth complications (1.4% versus 7.5%).

Targeted exemptions

The NHIS automatically collects premiums via payroll deductions for all workers in the formal sector. Other adults must pay a registration fee and an annual premium.

However, officials exempt the following groups from premium payments:

- Children under 18 (although children ages of 5 to 18 must pay administrative fees)

- Extremely poor Ghanaians enrolled in the LEAP program (see below: conditional cash transfers)

- People older than 70 years of age

- Pregnant women (eligible since 2008)

These fee exemptions aim to remove financial barriers to access and increase health system equity.

Conditional cash transfers

In 2008, Ghana launched the Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP) pilot, a cash-transfer and health insurance program targeted at extremely poor households. In 2009 and 2010, officials expanded the program nationwide. Eligible households also had to have a single parent with an orphaned or vulnerable child, an adult age 65 or older, or a person with disabilities that prevented them from working. In addition to free health insurance, participants receive bimonthly cash transfers of US$4 to US$8. The number of beneficiary households increased from 1,645 in 2008 to more than 146,000 across 185 districts in 2015.

Between 2015 and 2017, officials piloted a new program called LEAP 1000, which covered pregnant women and children younger than 12 months.

Some research suggests that LEAP has positively impacted NHIS enrollment. One study suggests that enrollment increased from 57% to 87.1% among sampled beneficiaries as a result of the program.

Free Maternal Health Care Policy

Since it declared independence in 1957, Ghana has implemented several policies to expand access to maternal care by removing user fees. In 1963, as part of the Nkrumah government’s efforts to achieve free health care for all, the MOH made all antenatal services provided at government hospitals free. In the 1970s and 1980s, antenatal care user fee exemptions survived multiple attempts to reintroduce hospital fees: for example, in 1983, pressure from international donors such as the United Nations Children’s Fund resulted in the government changing its plans to remove financial protection for antenatal services. (In fact, the fee exemption was expanded to include postnatal care.) The 1985 Hospital Fees Regulation that ushered in the unpopular cash-and-carry system for almost all hospital services maintained exemptions for antenatal and postnatal care, although financial constraints kept many hospitals from enforcing these exemptions—and women still had to pay to give birth in a health facility.,,

Despite these measures, maternal mortality remained high: in 1990, the national maternal mortality ratio was 740 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. The 1993 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey indicated that although national utilization of the free antenatal service was 86%, about half of the women who received the free antenatal care did not return to give birth at those facilities, in part because they were unable to pay for it.

In 2003, Ghana enacted a poverty reduction strategy using funds from the International Monetary Fund’s Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative for debt relief. The strategy included a plan to address the high maternal mortality ratio by introducing a fee exemption for delivery care for women living in the country’s four poorest regions: Northern, Upper East, Upper West, and Central. That benefit was expanded nationwide in 2005.

Despite the popularity of these fee exemptions, financial constraints kept the MOH from reimbursing health facilities for the fee-exempt care they provided. As a result, by 2007, many health facilities had stopped honoring the exemptions and fewer pregnant women sought care. Supervised deliveries fell from 45% in 2006 to 35% the following year. Maternal mortality increased and the government declared maternal health a national emergency.

To encourage pregnant women to seek health services, free maternal care was incorporated into the NHIS in 2007. However, the new scheme faced early hurdles because pregnant women who did not proactively enroll in (and pay premiums to) the NHIS could not receive the benefit. In July 2008, Ghana’s government introduced the Free Maternal Health Care Policy, which automatically registered pregnant women with the NHIS and ensured they received free comprehensive maternal health services including antenatal care, pregnancy-related emergency care, normal delivery care, cesarean section deliveries, and postnatal care for mother and baby.

By 2017, the maternal mortality ratio had fallen to 273.8 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, a 44% drop since 2000 (though still high by global standards). Research suggests that the Free Maternal Health Care Policy increased health care use by pregnant women. One study estimated that pregnant women with access to the policy were 97% more likely to use antenatal care services and 87% more likely to give birth at a health care facility compared to those without. However, during the study period, skilled birth care for the poorest women increased from just 30% to 38%. In comparison, the uptake of skilled birth care among the wealthiest women jumped from 56% to 93% during the same period.

Between 1990 and 2008, the percentage of births attended by a skilled health care worker increased with every new policy. Only 44% of births were attended by skilled personnel during the cash-and-carry era. This increased to 49% after free antenatal care was introduced and 54% following the arrival of free delivery care. It reached 58% when maternity care coverage was folded into the NHIS.

Read more about remaining challenges .

Bringing health care services to the community

In the decades since Ghana’s independence, officials have struggled to deliver key PHC services to all Ghanaians—especially those who live in rural communities. After structural adjustment mandated the adoption of the cash-and-carry fee system in 1985, health care became even more inaccessible to the country’s poorest people, many of whom lived in rural areas. In general, people in urban areas receive better care. For instance, at the turn of the 21st century, infant mortality rates in rural areas were 60% higher than those in cities.

Starting with the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund Bamako Initiative in 1987, pilot projects implemented in countries across West Africa aimed to improve the availability and affordability of health services in rural areas by strengthening community efforts to finance and manage health facilities and participate in health system governance and decision making.,

Community Health and Family Planning Project

In Ghana, the MOH adapted a version of the Bamako Initiative in which volunteer community health workers (who were paid informally with proceeds from the sale of medicines to their patients) delivered care to patients in six pilot districts. A 1992 evaluation found that this method of compensating health workers was inadequate, and in 1994 officials launched a new pilot initiative: the Navrongo Community Health and Family Planning Project (CHFP).

Navrongo CHFP pilot initiative

In the first phase of the pilot initiative, the Navrongo CHFP led to the restructuring of the program of the early intervention, changing community health nurses into community resident health care providers, renamed community health officers (CHOs). Through reorientation and training, the CHOs were deployed to communities within the experiment treatment zones. CHOs received 18 months of training focused on curative services, public health, family planning and immunization.

The second piece of the intervention added male volunteers who were recruited and trained from participating communities to provide more limited services. Their role was designed to build male leadership and participation in reproductive health activities. Those volunteers reported to local health committees whose members were in charge of procuring supplies as well as coordinating volunteer work.

Together, these health workers worked alongside traditional institutions, leaders, and social networks, including the cadre of volunteers who reported to local health committees, to deliver key health services such as family planning, preventive care, and immunizations.

The CHFP covered its costs by maintaining the cash-and-carry system.

Program design, implementation, and evaluation research was a key component of the Navrongo CHFP. Key lessons from the first phase of the Navrongo pilot informed its future iterations. For example, researchers learned that workers were more successful when posted to their home district, but not their home village. Villages typically seek nurses who are socially distanced from their communities and can maintain anonymity for people seeking family planning services.

The success of the Navrongo model encouraged officials to scale up the program, using health staff and community volunteers to bring essential health services to hard-to-reach places in Nkwanta from 1996 to 1998.

The Nkwanta pilot initiative

In 1997, the Navrongo Health Research Centre started a formal “exchange” program for their experimental study. Researchers in Navrongo invited officials in the Nkwanta health district in the southeastern Volta Region to test whether the Navrongo model would work in a non-research setting. Nkwanta was like Navrongo in some ways: it was a poor, isolated agricultural district with only a few facilities where residents could receive basic health services.

Within a year, the Nkwanta pilot had demonstrated that the Navrongo approach could be adapted to other regions and districts, as long as the adaptation launched in six key phases :

- Planning

- Introducing the community to CHPS

- Establishing community health compounds

- Providing community health centers with essential equipment

- Training community health officers

- Mobilizing volunteers

In 1999, health officials elevated those six key elements of the Navrongo model—now known as Community-Based Health Planning and Services (CHPS)—into national policy. The MOH’s goal was to expand CHPS nationwide by 2015.

Follow-up studies in Navrongo and Nkwanta found that CHPS had made a significant impact on community health. In CHPS’s first five years in Navrongo, for example, the maternal mortality ratio had declined by 40% and the childhood mortality rate by nearly 70% in communities located near the compounds where paid health nurses worked. It did not cost much to scale up and sustain, and the community mobilization activities had established a climate of trust that encouraged people—especially women and children—to seek care when they needed it. In 2004, a follow-up study in Nkwanta found that the average household now lived less than 9 km from the nearest health facility, compared to 14 km in 1998, and more than 63% of people in Nkwanta lived within 10 km of a health facility, compared to 44% in 1998.

The Ghana Essential Health Interventions Program

Although the MOH’s goal was to expand CHPS nationwide by 2015, researchers found that by 2008, implementation had stalled almost everywhere. There was no routine budget provision to pay for it, regions and districts did not have the managerial capacity to develop and sustain it, and the package of services it offered was often incomplete. For instance, CHOs often lacked the skills they needed to manage health emergencies, especially those involving newborn babies.

In 2009–2010, a group of Ghanaian researchers developed the Ghana Essential Health Interventions Program (GEHIP) to “test the proposition that a novel set of interventions could improve the impact of CHPS, accelerate its adoption by districts, and, thereby, improve the health and survival of children under 5” in four districts (compared to seven control districts) in the Ghana’s Upper East Region. , GEHIP implemented interventions aimed at strengthening the prevention and management of common childhood illnesses, simplifying data collection procedures using DHIMS2, improving administrative capacity among District Health Management Teams, and finding ways to mobilize funding (e.g., for the construction of CHPS compounds and health posts). Within four years, researchers found nearly complete coverage in the four GEHIP districts, reaching twice as many people as in comparison areas. Child mortality declined more quickly in the GEHIP districts than elsewhere, and contraceptive prevalence increased.

Read more about Ghana’s emphasis on evidence-based interventions and implementation research here.

CHPS+

In 2016, with the support of international development partners, the Ghana Health Service introduced the CHPS+ initiative, which aimed to expand GEHIP—especially its leadership development and community engagement programming—to all 13 districts of the Upper East Region, two Volta Region districts, and two Northern Region districts., The initiative’s goal was to build consensus in support of more widespread CHPS implementation, both locally and at the national level. Results from the study areas showed improvement in CHPS functioning as well as in key maternal and child health and immunization indicators. This is especially noteworthy since the end of the study period coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted health indicators worldwide.

Researchers argue that CHPS+ can be a valuable model for building health systems capacity and improving health outcomes nationwide.

Scaling CHPS

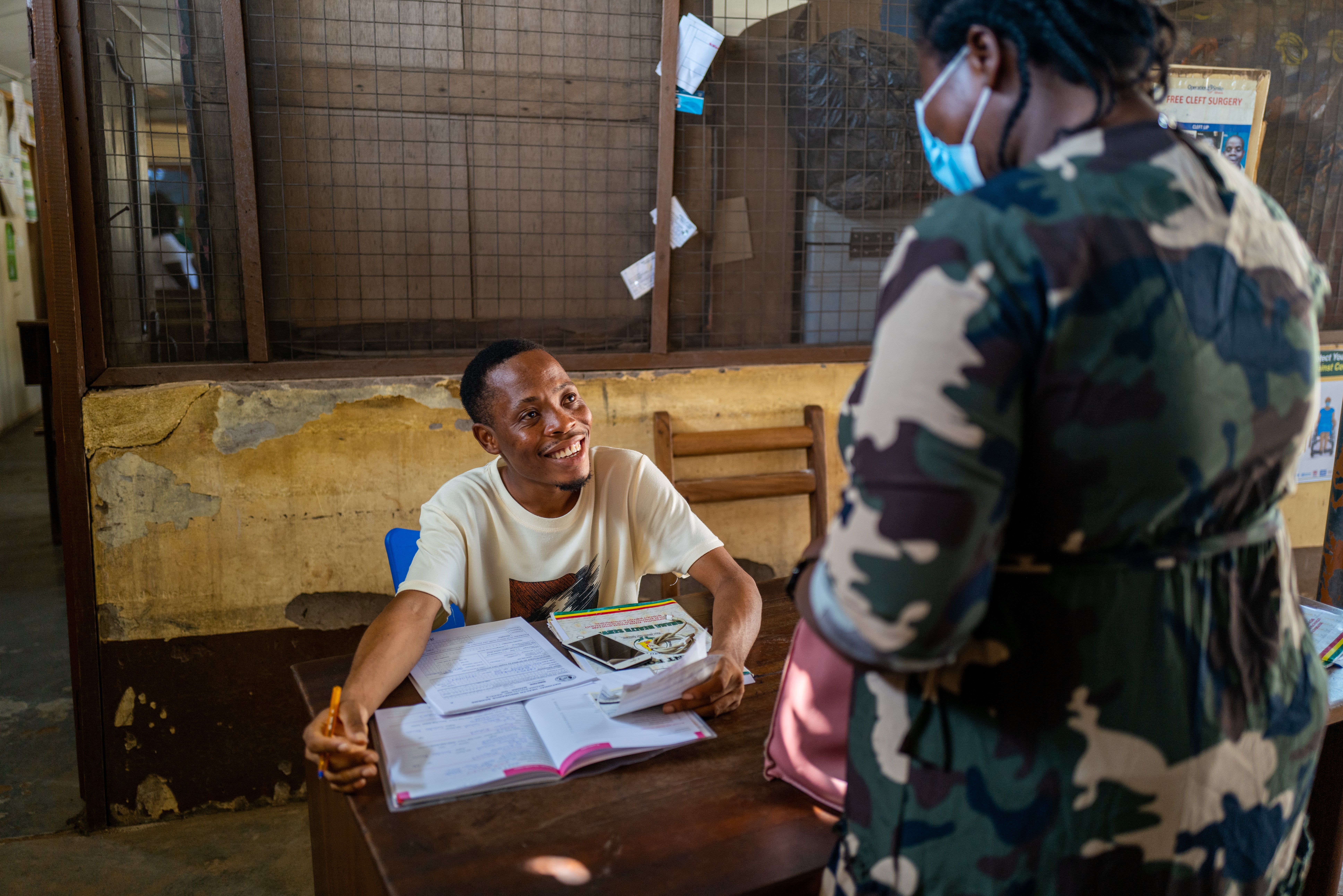

In rural and hard-to-reach communities across the country, the Ghana Health Service assigns salaried professional nurses (community health officers, or CHOs) supported by community leaders and volunteers (community health volunteers, or CHVs) to deliver home- and facility-based health services such as antenatal care, family planning, health education and outreach, and child welfare services., As of December 2019, Ghana had more than 19,000 CHVs and 2,500 CHOs.

To reduce patient travel time and encourage more people to seek care in their communities, CHPS built “compounds” in each of Ghana’s health zones. The compounds house the CHOs and serve as community clinics where CHOs and volunteers deliver PHC services. (When necessary, patients are referred to local health centers, district hospitals, and regional hospitals.) As of 2020, there were about 6,500 CHPS compounds across Ghana, covering nearly half of the country. Each compound serves about 5,000 people.

Research indicates that Ghana’s CHPS system does help to deliver essential PHC services, especially to people living in some rural areas. For example, studies show that where CHPS compounds are set up near health facilities, women and babies have better access to skilled birth care. Statistics from 2008 and 2014 showed a significant disparity in childhood immunization rates between children living in rural areas and in urban ones, which may have been associated with CHPS’s emphasis on delivering basic health services such as immunizations to people living in rural communities. However, those disparities have reversed in recent years. Many people who have used CHPS services report that they are satisfied with their experience, which is a significant step toward ensuring continuity of care.

As shown in Figure 15, immunization rates for measles and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine increased dramatically starting in 2012 before leveling off.

Figure 15: Ghana immunization coverage among 1-year-olds

Overall, CHPS expanded coverage and access to health services, strengthened community engagement with health care providers, and directed more resources toward health care. It also led to improved health outcomes, such as reduced child and maternal mortality.

National-level interview respondents saw CHPS as a strong contributor to better access to PHC. Some explicitly linked CHPS to an increase in health workers and a better focus on prevention and community-based care:

"We have had a lot of initiatives in the Ghana health system but CHPS is the best thing that happened to our primary health care. If we are able to strengthen it well, every community will have some health officers that will guide them to do the right thing, and we’ll be able to eradicate some of the diseases."

National-level interview respondent

"With CHPS, which is primary health care, the focus is preventing disease burden…. It’s a national strategy to deliver essential community-based health services."

National-level interview respondent

Read more about remaining challenges

Community health officers

The system of paid, trained community health nurses established by the Navrongo pilot project became Ghana’s CHO program. CHOs are salaried government employees who typically live in the health zones they serve.

CHOs are trained for two years at regional community health nursing training schools across the country. After those two years, they become community health nurses; after they complete a community-based internship, community health nurses become CHOs and are deployed to their CHPS zone.

The services provided by CHOs include:

- Maternal and reproductive health services

- Neonatal and child health services

- Integrated management of childhood illness

- Preventive care and tuberculosis and HIV management for adults

- Health education and outreach

- Patient follow-up

As of 2018, 15% of Ghana’s CHPS zones had a trained midwife on staff. CHOs can also be trained as midwives (their standard training excludes emergency obstetric care). CHOs are supervised by public health nurses, physician assistants, or administrators from subdistrict health facilities. In turn, they supervise the CHVs who work in their health zones.

Community health volunteers

CHVs are part-time lay workers who receive five days of training to provide basic health services for their neighbors within the CHPS system. They are nominated by community leaders and others at community gatherings known as durbars. Their work is supervised by the CHOs in their health zone.

CHV responsibilities include:

- Lead community mobilization efforts

- Support health promotion activities

- Manage minor illnesses

- Encourage pregnant women to use maternal health services

- Translate health messages into local languages

CHVs are volunteers, but they sometimes receive incentives such as T-shirts, bicycles, rubber boots, and reimbursement for their daily transportation costs.

Community health workers

In 2014, Ghana launched a program to pay a cadre of CHVs volunteers within the CHPS system. Like CHVs, CHWs were supposed to work in the community, not in hospitals, and were paid a regular salary from the Youth Employment Agency. However, after a change of government, the CHW program ended in 2016.

Engaging the community in health service delivery

Since 2000, Ghanaian health officials have implemented several initiatives aimed at facilitating community participation in health policymaking and program development, administration and oversight, and service delivery. This push for community empowerment aims to ensure that the health system is accountable to local needs.

Community case management

In 2009, Ghana’s MOH introduced an Integrated Community Case Management (iCCM) system, also known as home-based care, to reduce childhood mortality. It was implemented in all ten regions by the Ghana Health Service. iCCM included prevention, early case detection, and prompt and appropriate treatment of fevers, acute respiratory infection, and diarrhea in the community. Community members who received five days of training, were responsible for information, education, and communication activities to encourage hygiene measures, insecticide-treated net use, indoor residual spraying, and intermittent preventive treatment for malaria prevention in pregnant women.

While both iCCM and CHOs enable PHC delivery in Ghana, evidence shows that iCCM was more cost-effective in the Volta Region for the management of malaria, diarrhea, and suspected pneumonia in children under five. Additionally, iCCM has contributed to achievements in health equity, as it was associated with improved disease knowledge and health behaviors in the Northern Region.

Community health management committees

Community health management committees (CHMCs) are voluntary advisory groups that typically have around 10 members. They connect the community with the formal health system, make some decisions, mobilize financial resources to aid in the development of CHPS compounds, and help CHOs supervise the work of the CHVs.

Studies have found few formal guidelines about how communities should choose CHVs and members of CHMCs. In some communities, community durbars, or meetings that include chiefs, elders, and other leaders, screen and confirm the volunteers nominated by community-based organizations, religious and social groups, traditional leaders, and even by their neighbors. In others, elected representatives serving on district or village assemblies are drafted into serving on CHMCs.

Studies show that CHVs and CHMCs mobilize resources (including donated land, goods, and labor), improve accountability (especially via the scorecard system, which invites communities to identify system gaps), support health workers (sometimes with accommodations, food, and supplies), develop community health action plans in some communities, and support health education and case follow-up activities.

Evidence from the study districts indicates community involvement in key areas, such as priority setting and planning for health agencies, performance monitoring, resource mobilization, and aggregating and communicating patient feedback (Figure 16.) All four districts reported strong community involvement across health administration domains, regardless of district efficiency scores. As a key informant from Sagnarigu District said:

“The whole concept of the Community Health Committee is community leadership. So it is the community members who prioritize problems, pick things they think can work, and come out with proposals. We don’t impose any activity on them. They come out with their proposed activities to work toward resolving problems.”

Figure 16: Community involvement in funding mechanisms