In Peru, Exemplars research identified two ways (or pathways) through which reforms have over time improved PHC outcomes. The second pathway focused on improving access to health care. The following sections reflect the main themes comprising this pathway.

Key Points

Peru also implemented reforms intended to remove financial barriers to access. Expanding the country’s comprehensive national health insurance program reduced out-of-pocket spending for the lowest-income segments of Peru’s population and protected users from catastrophic health spending.

Before and during the Exemplar study period, Peru implemented reforms to its health system that improved geographic access to health services nationwide, such as by incentivizing health workers to move to underserved areas.

As the supply of health services increased, so did demand. Policymakers implemented further reforms aimed at ensuring sufficient human and material resources to meet that increased demand.

Peru also introduced holistic, population-focused comprehensive care models to tailor resources and the provision of services on the basis of need.

At the same time, multisectoral initiatives targeting the country’s poorest people have also notably improved primary health care (PHC) service coverage and outcomes. Some, like the conditional cash transfer program JUNTOS, were public programs aimed in part at reducing poverty overall.

Eliminating financial barriers and building demand for health care

Building a framework for comprehensive health insurance

Since the 1990s, policymakers in Peru have been expanding the country’s tax-funded national health insurance, gradually removing financial barriers to care and enabling comparatively broad access to PHC and selected specialist care.

- In 1999, the Ley del Seguro Social de Salud created EsSalud, a public, contributory (via payroll tax) health insurance scheme for wage earners in Peru’s formal sector. By 2017, EsSalud insurance covered 27% of Peru’s population. (See Figure 8 below.)

- In 2002, officials created the Seguro Integral de Salud (SIS), a prepayment scheme funded through general taxation for poor Peruvians—in particular children, pregnant women, and older people living in poverty. Initially, SIS provided free preventive services and basic and emergency care for approximately 35% of the country’s poorest people.

- In 2007, the Ministerio de Salud (MINSA) added semicontributory, or partially subsidized, coverage to the SIS program for informal workers who earned less than $1,000 per month. By 2017, it covered 47% of the population.

- The Universal Health Insurance Law of 2009 turned SIS—and its contributory counterparts EsSalud and the insurance regimens associated with the armed forces and the police—into a framework for mandatory universal health insurance.

Policymakers established an essential benefits package, the Plan Esencial de Aseguramiento en Salud (PEAS), to which all Peruvians are entitled. PEAS aimed to ensure comprehensive care for Peruvians at all stages of life by defining some 140 common health conditions (65% of the causes of morbidity) and listing the benefits and services associated with them that public and private health facilities were required to offer. The law prohibits hospitals and health centers from charging user fees for covered services to patients covered by SIS; instead, the insurance scheme pays for them directly.

Peru’s push to universalize health insurance coverage has done its part to make health services more accessible, at least financially. Encuesta Nacional de Hogares (ENAHO) surveys showed that in 1997, just 23.5% of Peru’s population had some form of health insurance. In 2008, 53% did. As Figure 8 shows, by 2017 84% of the population was insured.

Figure 8: Insurance coverage by scheme

This move toward universal health insurance has also reduced out-of-pocket (OOP) payments for consumers nationwide. At the beginning of the Exemplar study period, OOP expenditures composed almost 40% of health spending, compared to less than 30% in 2019. Because of the targeted nature of SIS, most of those OOP payments accrue to those who can afford to pay them.

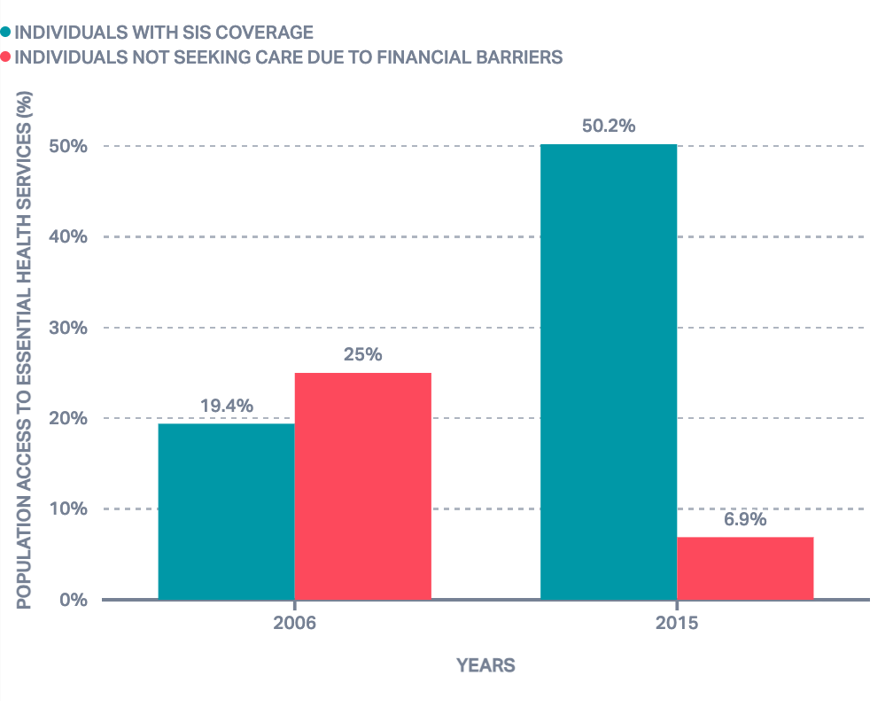

Evidence also suggests that these insurance programs have improved access to care, especially for low-income Peruvians and those living in rural areas, particularly women and children., Generally, access to health insurance improves health by encouraging people to seek care.

Figure 9: Peru demonstrated improved access to health care

Meeting rising demand for PHC in Peru

Human resources for health

In 1972, Peru’s military government introduced the Servicio Civil de Graduandos (SECIGRA) program: a compulsory unpaid PHC rotation in underserved communities for all medical students. In 1980, SECIGRA became Servicio Rural Urbano y Marginal de Salud (SERUMS). SERUMS service was (and remains) a requirement for aspiring doctors, dentists, nurses, midwives, pharmacists, and other health workers who wish to seek further training or jobs in the public sector. This means that a substantial proportion of health providers nationwide start their careers working in rural areas.

In 2009, policymakers began to use poverty maps developed by the Fondo de Compensacion Social y Desarrollo (FONCODES) to identify SERUMS districts. MINSA data from 2011 showed that this shift was better at targeting poorer districts and thus improved the equitable distribution of health professionals. In 2008, just half of Peru’s poorest districts had a SERUMS physician, compared to almost 90% in 2011.

One 2022 study showed that in rural areas, SERUM workers composed 58% of doctors, 30% of nurses, and 18% of midwives.

Other reforms aimed at supporting health workers and improving their working conditions included the SERVIR program, established in 2001 to improve human resources management. It improved recruitment, developed leadership skills, professionalized managers, and supported pay raises so managers in the public sector earned the same as their private sector counterparts. Some study regions implemented performance-related bonuses through SERVIR to attract and retain senior staff. For instance, in San Martin, SERVIR increased the pay for skilled managerial staff to equal salaries offered in the private sector, increasing staff motivation and improving service quality and coverage.,

Figure 10: HRH density per 10,000 population (doctors, nurses, midwives)

Provider payment mechanisms

As part of the 2013 reforms that expanded the country’s comprehensive care networks, MINSA introduced a blended capitation and pay-for-performance provider payment system for PHC to encourage the provision of key PHC services to meet demand—including for newborn and child health, nutrition counseling, childbirth in health facilities, medical and dental consultations, and early cancer detection.

Service delivery through the public sector is provided in public facilities owned by autonomous regional governments (called GOREs) and managed by health implementation units. These implementation units facilitate payments to providers from the national SIS health budget. Direcciónes Regionales de Salud, or Regional Health Directorates, work closely with the GOREs to shape regional health policy and plans. The interactions and processes between these entities are carefully calibrated to ensure SIS reimbursements are designed to address facility case load and need.

In some settings, blended provider payment mechanisms including both capitation and pay-for-performance components have been linked to improved health expenditure growth, efficiency, and equity. The capitation component of these payment models also ensures providers have a predictable revenue stream. To ensure predictable revenue and performance-based incentives, capitation payments in Peru include both a fixed and a variable component. The fixed component is adjusted for poverty, geography, demographics, and other factors, and is dually underpinned by Peru’s strong data practices, including yearly national and subnational demographic and health surveys. The variable component is determined by providers’ performance on predefined indicators according to agreements with the GOREs. SIS disburses the majority of capitation payments (~80%) to implementation units at the beginning of the year, and the remaining amount (~20%) is granted midyear based on compliance with predefined performance indicators.

Expanded comprehensive care networks

In 2003, MINSA developed the Modelo de Atención Integral de Salud (MAIS), which defined key health needs for different populations: vaccination, nutrition services, reproductive health, preventive care, and more. It also implemented outreach and mobile health care services and formed micro-networks for the direct provision of health services aligned to these needs.

However, health system fragmentation limited the reach and cross-cutting promise of this early version of MAIS, and in 2011 it became the Modelo de Atención Integral de Salud basado en Familia y Comunidad (MAIS-BFC). MAIS-BFC takes a more comprehensive family- and community-based approach to health care and includes programs specifically designed to strengthen PHC, including investments in equipment, medicine, training and incentives for health providers, and integrated networks of health services, but it was never implemented at scale.

Later, in 2013, as part of the reforms aimed at establishing a universal health coverage system in Peru, MINSA added two key programs to the comprehensive care networks that deliver PHC.

- In Peru, the burden of mental health disorders is unusually high, and before 2013 Peruvian National Institute of Mental Health studies showed that a great majority of those who needed mental health care did not seek it. The 2013 reforms to the health system changed the way mental health care services are delivered, integrating them into local primary care facilities and introducing support services such as community mental health centers and inpatient facilities (not psychiatric hospitals) for those with severe illness. SIS insurance now covers mental health services, eliminating many of the financial barriers to access that once kept Peruvians from getting the care they needed, and a dedicated results-based budgeting program enabled additional targeted spending on these services. Evidence shows a high degree of user satisfaction with these reformed services, and providers reported that teamwork eased the implementation of program activities.

- Cancer is one of Peru’s leading causes of death. Since 2011, MINSA has prioritized cancer prevention and treatment, and in 2013 health officials established Plan Esperanza, a national comprehensive cancer care plan aimed at improving access to cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment among Peru’s poorest citizens. SIS covers Plan Esperanza services, which are delivered in community health facilities nationwide.

- Other pillars of Plan Esperanza include oncology education and research, social mobilization for cancer prevention and control, and program monitoring and evaluation. Plan Esperanza also incorporates population-based data analysis and systematic reviews and national studies on cancer prevention and early diagnosis. Its overall aim is to reduce cancer incidence and mortality nationwide.

- Both programs relied heavily on community-based management of chronic patients. This decentralization of chronic care management to local levels improved linkages to care and continuity of treatment.

Access to essential medicines

Another part of Peru’s efforts to reform its health system in the early 1990s was the establishment of the Programa de Administración Compartida de Fármacos (PACFARM), a decentralized pharmaceutical management program intended to improve the supply of essential medicines to PHC facilities nationwide. PACFARM developed a list of 63 essential medicines and supplies for all facilities in the public health network, purchased them using a self-supporting revolving fund (managed, in part, by community members serving on local committees), and stored them in regional warehouses. It also acquired and distributed drugs donated by NGOs and other international partners.

Decentralization made the distribution of essential medicines more efficient, because officials at the lower levels of the system estimate demand to determine the level and quantity of medicines needed and place orders accordingly (pull system).In a centrally operated push system‘, by contrast, manufacturers or the central government decide the type and quantity of medicine to be delivered to lower levels based on projections that might not align with need, and wastage can occur.

Also, Peru uses Sistema Integrado de Suministro de Medicamentos e Insumos Médico-quirúrgicos (SISMED), a national stock management system that enables health officials to digitally monitor the supply of key medicines and to track drug distribution and use. SISMED helps prevent stockouts.

Multisectoral antipoverty initiatives

Multisectoral initiatives targeting the country’s poorest people, the conditional cash transfer program JUNTOS (see below), helped improve PHC outcomes as they reduced poverty nationwide.

Conditional cash transfer programs

In 2005, policymakers in Peru launched a conditional cash transfer program, known as JUNTOS, targeting households in extreme poverty—especially those with pregnant, young, or elderly family members—and Indigenous families in rural areas, as well as those most exposed to violence in the guerrilla war of the late 1980s and early 1990s. In 2007, the program expanded to include food-support for children at risk of malnutrition. Beneficiary districts and families are identified using ENAHO demographic data, and JUNTOS participants are automatically enrolled in SIS health insurance.

The goal of JUNTOS is to break cycles of intergenerational poverty and to encourage participants to use public health and education services. Consequently, participants with children under 16 can stay in the program as long as they get regular health checkups and children older than six attend school at least 85% of the time. New mothers must also attend counseling sessions in which they learn about the importance of exclusive breastfeeding, proper complementary feeding, and hygiene; parents must commit to obtaining identity cards for their children; and young children and pregnant women in the household must follow a rigid schedule of growth monitoring visits. (JUNTOS programming can also include lessons in financial literacy sometimes delivered by “mother leaders” and other community members.)

Evaluations of the JUNTOS program have found an improvement in the nutritional quality of participants’ meals, a decrease in poverty, and an increase in visits to health facilities. Some JUNTOS participants also experienced reduced underweight among women and reduced anemia and acute malnutrition in children.