Key Points

Established immunization as a flagship program for public health through strong government commitment.

Brought services closer to communities through health posts, health huts, and trusted community health workers (CHWs).

Implemented the Reaching Every District/Reaching Every Child strategy to systematically improve coverage, especially for underserved communities.

Implemented tailored and targeted strategies to generate demand and combat misinformation.

Committed to health, fostering shared ownership at all levels

Since 2001, Senegal’s constitution has identified health as a human right, asserting that “The state and the public authorities have the duty to ensure the physical and moral health of the family and in particular, of the disabled and the elderly. The State guarantees families in general and those living in rural areas in particular access to health and welfare services.” A strong commitment to health and vaccines was apparent from all levels in Senegal, including national and subnational government authorities, external partners, service providers, and community members.

Many informants referred to immunization as a “flagship program,” and some noted that post-vaccination declines in diseases such as diphtheria, pertussis, and measles contributed to political will for improving immunization.

“This is the flagship program; it represents 50% of our activities. To have health, the first step is prevention; you have to try to prevent disease. Most of these diseases have no treatment, so you should try to do the treatment with vaccination.”

- Health post head nurse, Tambacounda

The Plan National de Développement Sanitaire et social (PNDSS, National Health and Social Development Plan) is set forth every ten years to ensure continuity across successive political administrations.,, Under these plans, resources are allocated from the national level to health districts based on bottom-up communication. District-level officials are responsible for the immunization programming within their communities; they send budgets to the national level and independently manage the funds they receive.

“Success is ensured, most often by the district. So, funding or not, the district ensures functioning. So, if there is funding, we try to use the funds that have been invested. But if that is not the case, the district is required to carry out its activities, because it is part of the sovereign functioning of the district.”

- Health district immunization officer, Ziguinchor

Key informants noted that community-led health committees facilitated the adaptation of vaccine programming to meet local and context-specific needs by connecting leaders in the community to health personnel and CHWs. In 2018, community-level ownership was codified when Comités de Développement sanitaire (CDSs, community health development committees) were established as the lowest administrative unit in Senegal. According to a 2019 evaluation, the government of Senegal and WHO’s Senegal office bolstered the capacities of each CDS to facilitate the provision of primary health care services at the community level following the decentralization of care.

Each CDS connects local decision makers with individuals in the health sector, including nurses and CHWs. CDS members are elected and must live within the service delivery area. Each CDS is typically led by the mayor and includes neighborhood delegates, women’s representatives, and religious leaders. CDSs play a central role in the funding, management, and adaptation of vaccination programming. They control resources from user fees paid to health facilities, donations from their communities, and funding by external partners.

CDSs provide funds for many aspects of health service provision. For immunization, this may include transportation, cold-chain maintenance, facility improvements, consumables, training, and materials for campaigns and outreach. CDSs also provide CHWs (who typically function as volunteers) with gifts, equipment, training, and other forms of support.

“Its role as CDS is to facilitate the management of activities at the level of health [posts]. I believe that the CDS, especially with regard to vaccination, supports us, especially if there is a gap of funding or when an activity whose funding is not sufficient to carry out this activity. The CDS also participates, so it participates not only financially but also in relation to the meetings with the ideas expressed for their point of view. Therefore, it participates to improve the indicators.”

- Immunization surveillance official, Dakar

Senegal applied that commitment and shared ownership to strengthening immunization programming and implementation.

Strengthened the broader health system

Senegal has committed to improving access to health care, with strategies focusing on health system strengthening and community health initiatives. Expanding access has coincided with large improvements in multiple measures of child health, including vaccination coverage and under-five mortality.

Expanded and improved health posts and health huts

Health post expansion and improvement were consistently mentioned as catalysts for increasing vaccination coverage. Senegal expanded health facilities and increased human resources for health with help from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance; the US Agency for International Development (USAID); and other partners.,

“If we look at the district level, there are areas that were very remote from the health post [that served the area]. But as soon as we create a new health post which is closer to [the community members], for the people who come from far away, the posts will be closer to them. . .. It makes the services more accessible, because before it was mostly mobile outreach.”

- Health district communication official, Tambacounda

Health posts also require qualified personnel and consistent training and supervision. As of 2016, Senegal’s complement of registered nurses and midwives is staffed at over 80% of national targets. Health workers are concentrated in the more prosperous western parts of the country, and gaps remain in more rural areas.

Comparison of staffing targets to reported staffing

| Role | Staffing Target | Reported staffing (2016)2 |

|---|---|---|

Registered nurses | 1 per 5,000 population | 1 per 5,942 |

Midwives | 1 per 1,500 to 2,000 women of reproductive age | 1 per 2,233 women of reproductive age |

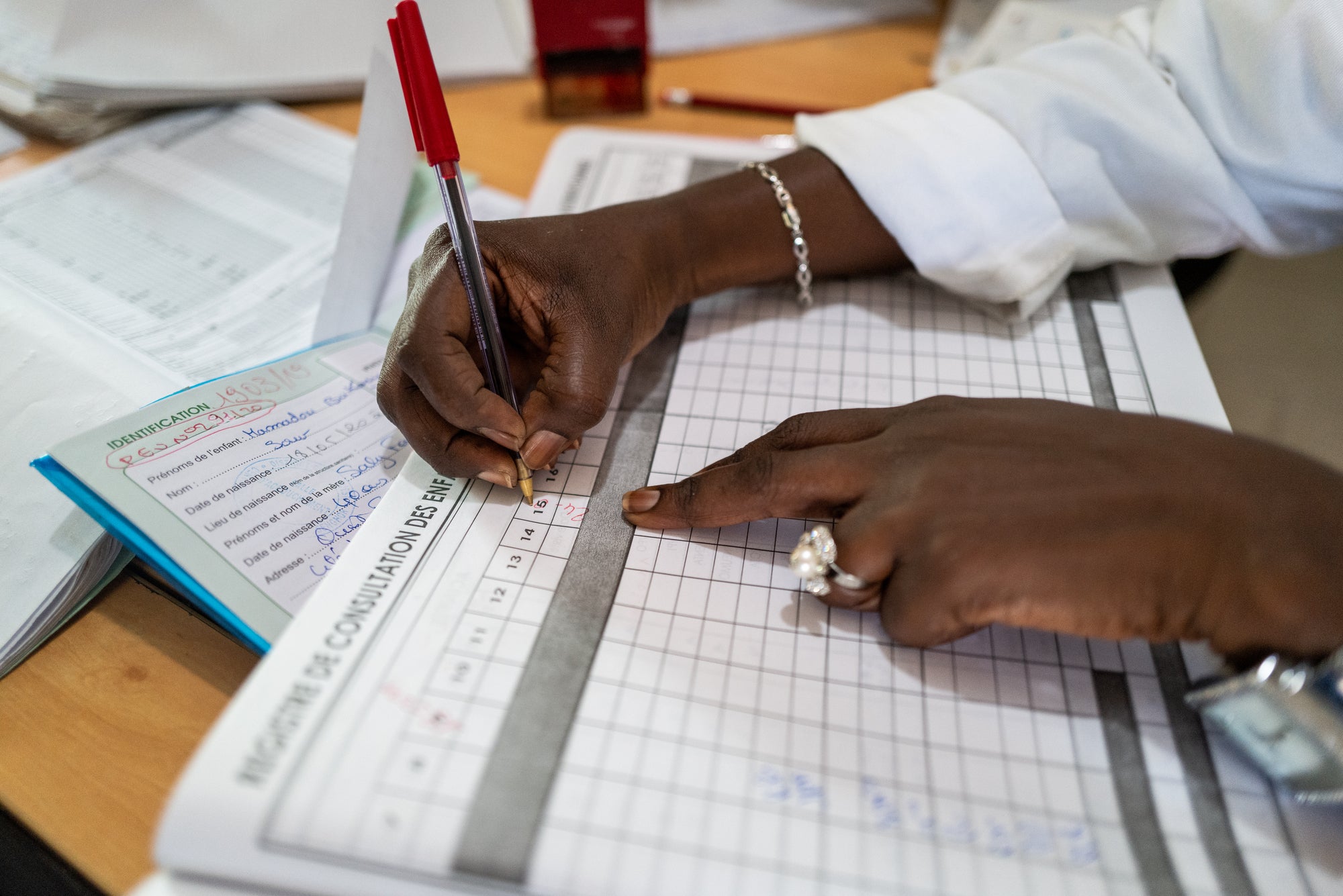

Each health post is managed by a head nurse (ICP, infirmier chef de poste), and the success of vaccination programming rests on their shoulders. In addition to conducting vaccination clinics at the health post and in outreach locations, they are responsible for managing the day-to-day operation of the health post, training and supervising CHWs and health post staff, and developing action plans in partnership with community groups such as the CDSs. Many respondents reported on the influence that ICPs had on their health post and catchment area.

“They [communities] achieve this [high] performance with the commitment of the ICP first and the commitment of community actors. Because if the ICP is well engaged, it is sure that the actors are too.”

- Health district primary health care supervisor, Dakar

Especially in impoverished rural areas, health huts bring services closer to communities. Health huts were originally built and operated by donor-supported programs, but in 2014 Senegal incorporated them into the formal health system. To strengthen sustainability and local ownership, responsibility for their supervision was transferred to local entities such as health districts and local collectives.,

In spite of this expansion, facility access still varies widely across Senegal. To improve access for families who live further from health facilities, Senegal has implemented outreach strategies as discussed further in the Equity section.

Media Travel Time to Closest Facility with RI Services

Median Travel Time to Closest Facility" figure Please update citation to "Liu PY, Fullman N, Gueye D, et al. Quantifying drivers of childhood vaccination in Senegal: a modeling analysis based on the Exemplars in Vaccine Delivery Framework. Working paper.

Established district community health worker cadres, including bajenu gox, or “godmothers”

To provide additional human resources for community health programming and outreach services, the MSAS has established multiple cadres of volunteer CHWs, collectively known as agents communautaires de prévention et de promotion (ACPPs, or community agents of prevention and promotion). CHWs are selected by the communities they serve, and they generally work as volunteers rather than paid staff. As a head nurse reported, “We express the need, and the community will take care of it.” Multiple respondents recognized the ACPPs for their strong connection to their communities and their work ethic:

“Vaccination is everyone’s business, so as community health workers, they come from the community, they know their locality better than we do and they are always in direct contact with their population. . . . This is why [community health workers] cannot be taken out of these results—because they strongly participate in the achievement of these results. They can make house visits, whether there is resistance, they tell us, speak as the person in charge of the structure since we have more arguments to convince the parent about immunization or other health activities. In all the activities we do, they are with us.”

- Health post head nurse, Ziguinchor

Cadres of community health workers (ACPPs)

| Cadre | Role | Contribution to immunization |

|---|---|---|

Relais, or relays | Conduct promotional and preventive interventions in many health areas, generate demand for services, and link clients to health huts and facilities. | Build demand for disease prevention and health promotion activities by promoting community awareness. |

Bajenu gox, or “godmothers” | Support maternal health and child health initiatives through community mobilization, referrals, and follow-up. | Inform community members of vaccination days and check vaccination cards to assess which children should attend. |

DSDOMs: dispensateurs de santé à domicile, or home health care workers | Provide home-based integrated community case management for malaria, diarrhea, and acute respiratory infections for children in remote communities. | Support vaccination clinics by managing crowds, recordkeeping, and disposing of waste materials. |

ASCs: agents de santé communautaire, or community health workers (CHWs) | Provide basic reproductive, maternal health, and child health services under the supervision of an ICP at the local health post. | Follow up on dropouts and mobile families to encourage parents to vaccinate their children. |

Matrones, or birth assistants | Birth assistants with 3 to 6 months of training, typically based at a health hut. Considered unskilled birth assistants, matrones refer complicated cases to the local health post.13 | Educate families about the importance of immunization and encourage mothers to bring their infants to vaccination events. |

The relais and the bajenu gox are widely seen as critical to the success of the vaccination program.

Relais have wide-ranging responsibilities. In addition to community engagement for immunization, they provide postnatal care and birth control services; treat malaria, diarrhea, and respiratory infections; administer deworming medication and vitamin A supplementation; distribute insecticide-treated bed nets for malaria prevention; and educate communities on health topics. Relais must be literate, to enable written communication and recordkeeping. They are trained and supervised by head nurses and may also receive field supervision by midwives and nongovernmental organizations.

The MSAS instituted the bajenu gox program in 2009 to address the lack of human resources for community health outreach and support. Bajenu gox must be older women who are “proven female leaders” and are drawn from the community in which they work. As elders and grandmothers, bajenu gox are deeply respected, making them particularly powerful advocates for reproductive and maternal and child health.

“The [bajenu gox] should be the ladies’ confidants. Family planning, antenatal care, vaccination, postnatal visits . . . all that is the role of bajenu gox. In our language, a bajene is someone we can relate to or confide in all the time, if a woman has problems even at the level of her household. . . . it is a well-known bajenu gox in the community who is the custodian of many secrets.”

- Health post head nurse, Ziguinchor

Bajenu gox build relationships of trust with community members. These relationships are facilitated by their pre-existing respect as female elders in the community. Mothers appreciated their assistance for pre- and postnatal care and their support during birth. In focus groups, women credited bajenu gox for bringing vaccination services to their communities. Many mothers specifically praised them for taking the time to explain diseases that vaccinations targeted, and for engaging in follow-up and individualized planning.

“In our neighborhoods, each time there is a vaccination to be given, they identify the people concerned and accompany them to be vaccinated. Because vaccination is very important, before we said that without it we could catch all kinds of diseases such as measles and others, but now we have more vaccines and thank God we have fewer diseases, and all our children are protected.”

- A mother interviewed in Dakar

Bajenu gox hold education sessions for women of all ages to correct misinformation and mediate between different age groups. Within the safety of a group, women could resolve differences on sensitive health questions. For example, older women sometimes believed that because they had not received vaccinations, they were unnecessary or could be dangerous. In addition, social norms discouraged daughters-in-law from questioning their mothers-in-law. Bajenu gox served as mediators, delivering information as trusted peers.

Implemented the Reach Every District strategy and introduced new vaccines

Starting in 2002, Senegal piloted a set of innovative approaches to increase vaccine delivery and safety in two regions, Saint-Louis and Matam. DTP3 coverage in project areas increased from 51% to 91% in just two years. Those approaches have now been codified as the Reaching Every District/Reaching Every Child (RED/REC) strategy, expanded nationwide in Senegal, and adopted in many other countries.,,

In implementing the RED/REC strategy, Senegal established and strengthened these essential functions:

- District-level decision making: Each health district develops an immunization action plan with the goal of reaching every child within its jurisdiction. This plan informs funding from higher levels.

“This plan really helps identify problems . . . and to see each district according to . . . what strategies must be implemented to improve coverage or to overcome these bottlenecks. So, it is a plan that is very important and has contributed to achieving vaccine coverage.”

- Health region immunization official

- Community mapping to find and count families, especially hard-to-reach families: Head nurses, ACPPs, and CHWs map the families in their catchment areas by going door to door to identify who lives in each village; which households have children; and of these children, who are vaccinated. These maps help to identify areas with low coverage or high dropout rates and prioritize them for outreach.

“When we map the children, we really know where this child lives, there we will not have much trouble to find the child. . . . I’d know if there was a child who had not come, the irregular. I automatically detect it. . . . Is this a refusal or another absence case? So here too, the ICPs must try to map the children at the level of their area of responsibility; it can decrease the cases of absence.”

- Health district supervisor, Tambacounda

Micro-planning to achieve immunization targets: Health workers, ACPPs, and members of the CDS meet each month to determine the dates and locations of outreach and mobile sessions (see table below); ensure that sufficient personnel, fuel, vehicles, and other resources are made available; and coordinate activities such as social mobilization and follow-up with children who missed doses. Community engagement in the planning and implementation of activities has led to greater community ownership over the RED/REC strategy.

Delivery strategies in Senegal

Fixed post | Services offered in a health facility (health center or health post), serving communities within 5 km of the facility. |

Outreach | In “advanced strategies,” services are delivered in communities 5–15 km from the health facility. Health workers based at the local health facility go to the community and return to the facility in the course of a day. In “mobile strategies,” services are delivered by mobile teams that travel to locations more than 15 km away, staying at least one night. For both advanced and mobile strategies, vaccination sessions are conducted in health huts, schools, or other public spaces. |

ACPPs help to implement these micro-plans. For example, relais often implement the communication plan for health promotion and prevention activities. Bajenu gox can specifically target women’s groups, since they have established relationships already.

- Services tailored to the communities: Senegal offers an integrated package of primary health care services, including family planning, antenatal care, vaccinations, nutritional counseling, and treatment for childhood illnesses such as malaria, pneumonia, and diarrhea. Integrated service delivery is more efficient for health staff and families alike. Location and timing are adjusted to enable everyone to gain access to care, in some cases providing services on weekends and evenings, at mosques or farms. In remote areas in the northern regions of Senegal, immunization sessions were conducted at rice fields.

“It also dawned on us that the parents did not refuse the vaccination but that they were rather busy [with] their daily occupations. It is our duty to go to the populations when they are available, and not the other way around.”

- External partner, national level

- Monitoring results and using data for decision making and planning: Community maps helped facilities decide how many vaccines should be ordered. To increase coverage and reduce dropouts (see figure below), nurses reviewed vaccination registries with ACPPs and sent them to bring the mother and unvaccinated child to a vaccination session. In some cases, if children moved and did not complete their immunizations, nurses from one health district would contact nurses in another health district to follow up on those children’s vaccination schedules. (See the Improved disease surveillance and coverage monitoring section for more examples.) These “defaulter tracing” strategies have helped Senegal reduce dropout rates over time.

Comparing DTP1 and DTP3 coverage relative to GVAP Targets for drop-out, 2000-2019

Although Senegal has made rapid progress in improving the overall reach of immunization programs, there is still a need to focus on areas where less progress has occurred, such as the Kédougou region in the southeast corner of the country. Lessons can potentially be applied and adapted from approaches that have worked in other areas to accelerate gains, such as in the northern and northeastern regions.

No-DTP Prevalence in Senegal

Percentage of under-1 children with 0 doses of DTP

- New vaccine introductions: The introduction of new vaccines has reinforced RED/REC strategies. Between 2004 and 2018, Senegal introduced vaccines against hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae type b, pneumococcus, polio (inactivated vaccine), rotavirus, rubella, and yellow fever. Immunization was expanded beyond infancy with an additional dose of measles-rubella vaccine in the second year of life and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination for young adolescents.

Informants noted that vaccine introductions strengthened immunization programming in general by emphasizing equity and coverage, improving infrastructure (particularly supply and cold chain), training and monitoring personnel, and building awareness and demand among the general public.

In spite of these improvements, readiness scores varied from facility to facility across Senegal between 2012 and 2019, showing room for further improvement, especially in the area of cold chain equipment (see figure below).

Quartiles of Facility Readiness Index

Liu PY, Fullman N, Gueye D, et al. Quantifying drivers of childhood vaccination in Senegal: a modeling analysis based on the Exemplars in Vaccine Delivery Framework. Working paper.

Generated demand for vaccinations through community engagement

Community engagement has deep roots in Senegal, dating back to the Primary Health Care Strategy of 1978, and is a core component of the RED/REC strategy., In Senegal, public awareness and demand for vaccines was generated through engagement with community actors, education from community health workers and volunteers, school outreach activities, and extensive media engagement. This has likely contributed to high levels of vaccine confidence in many regions (see figure below).

Regional variation in vaccine attitudes

Engagement with community actors

Community actors include religious leaders, traditional chiefs, mayors, school directors, women’s group representatives, members of community watch committees, and other respected individuals.

The MSAS collaborates with community actors in planning, policy development, and implementation of health activities. For example, community actors are invited to planning sessions for immunization campaigns. Neighborhood delegates provide feedback on communication strategies, which are then implemented by health care workers and community members.

Communities and MSAS work together to combat vaccine hesitancy and promote mutual responsibility and ownership of health outcomes. MSAS staff and ACPPs work with communities to share information about immunization sessions, build demand for immunization, and address challenges within the community. Trusted by the population, ACPPs help to build trust in health workers and the health care system.

“First, we start by sending them our action plan that they already have with them. And at 72 hours before the activity, we remind them of the activity. We call them to tell them that at such-and-such a time we will be in the district. And at 48 hours they inform the population.”

- ACPP interviewed in Dakar

Community members often contribute in very visible ways. Community leaders sometimes offer their homes to be used as vaccination sites. Chiefs prepare the venues and welcome health workers and community members. Homes may be used for mothers’ group discussions. Religious leaders may educate their congregations either before or after religious activities. Traditional healers are trained on the importance of vaccination, spread information about immunization, and encourage families to keep appointments and retain vaccination cards.

“We mobilize the local youths, they go door to door on the day of the vaccination to inform us that we have to go to the post in the evening. If the person can read, he will see the date of the appointment on the booklet. We can also ask someone to read us the date or even come here to the post with the booklet so that they can tell us the date.”

- A mother interviewed in Tambacounda

These practices mirror those from the other Exemplar countries (see figure below). In Zambia, traditional leaders and neighborhood health committees play an important role. In Nepal, mothers’ groups and female community health volunteers are crucial to community engagement.

Examples of community-based strategies to improve awareness and demand

| Strategies | Common approaches | Highlights | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Dakar | Ziguinchor | Tambacounda | ||

Vaccination sessions | Specific days are assigned for vaccination. | Vaccination sessions are held daily in most health districts. Elsewhere, vaccination sessions are held twice weekly. Immunization acceleration days are held where children who are not yet vaccinated are searched for by community workers and brought to a designated place to get vaccinated. | Catch-up days are conducted for children who missed vaccination at any point. Vaccination sessions are held twice weekly. Schedules are made based on the availability of mothers. Mothers are taught about vaccination. | Specific days are assigned for vaccination. Community actors gather children for vaccination. |

Community actors | ICPs and ACPPs engage with religious and other community leaders to build support for immunization. Village chiefs and community leaders foster demand for immunization. Traditional healers direct mothers to health posts. Community actors take children to get vaccinated when their parents are not available. | Imams speak about vaccination every Friday at the mosques. | Imams announce days of vaccination. Village chiefs gather mothers for vaccination. Parents call to ask about next vaccination dates. Community-based organizations look for irregularities using information compiled by the ICPs at the post. Watchdog committees conduct personalized follow-up of children from birth until they get all vaccines. | Committee meetings are held every 2 to 3 months. Community-based organizations look for irregularities using information compiled by the ICPs at the post. Youth clubs search for children and refer them for immunization. |

Personal communications | Local languages are used to facilitate communication. Home visits are conducted. Dialogue days are held with communities and populations to discuss problems and solutions related to vaccination. | Registers are checked regularly. and children who missed vaccination are followed up. | Registers are checked regularly, and children who missed vaccination are followed up. | Bajenu gox look for children in nomadic communities. |

Engaging families | Mothers’ groups are brought together by community actors to discuss vaccination. | “Circles of fathers” get involved in convincing other fathers to allow their wives to bring children for vaccination. Grandmothers remind mothers about vaccination dates and importance of vaccination. | Village savings-group meetings are used to pass information about vaccination to mothers. Fathers remind mothers about vaccination appointments. | Fathers check home health records and remind mothers about vaccination appointments. Grandmothers remind mothers about vaccination appointments. |

School outreach | School children are given information to pass to their parents. | School children are given information by teachers on vaccination to pass home to their parents. | School children are given information by teachers on vaccination to pass home to their parents. | School children are given information by teachers on vaccination to pass home to their parents. |

Media engagement | Radio and TV pass along information. | Community radio allocates hours to discuss health. Newspapers include information on immunization programs. | Community radio allocates hours to discuss health. | Media is less engaged than in other provinces, due to lack of electricity and poor reception. |

Educational materials | For illiterate audiences, materials have illustrations as well as words. | Flyers, posters, and visual aids are used. | Advice cards, pamphlets, notebooks, leaflets, social networks | Flyers, posters, advice cards, illustrative images in booklets are used. |

Engaging fathers in health decisions

As men tend to be the household decision makers in Senegal, health education activities actively engage fathers to build support for vaccination. Some fathers were specifically selected as ACPPs to share information about immunization with other fathers within their communities. Male ACPPs hold discussions with fathers while female ACPPs engage with mothers. Fathers’ groups, which were initially formed to promote acceptance of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines for young girls, now discuss the importance of routine infant vaccination as well.

“So, there is the ‘circle of husbands,’ since we are in Africa, and the power belongs to the husbands. So, we also involve these husbands who also sensitize their fathers so that they can agree to let the women bring the children to be vaccinated. There are a lot of strategies that are implemented in the districts, really to reach the maximum of the community.”

- Health region officer

Messages about the value of preventing illness may particularly resonate with fathers, who typically control household finances.

“A child who has respected the entire immunization schedule is better off than a child for whom this is not the case. And they themselves have realized this. It also allows fathers to save money because a child who is always sick requires a lot of expense.”

- ACPP interviewed in Ziguinchor

However, some fathers forbid their children from being vaccinated, citing reasons such as fear of side effects or infertility, belief in divine powers, and general defiance toward the health system. This shows the need for continued engagement and greater trust between health workers and communities.

“Let me give an example: if we do a vaccination and we realize that in such-and-such a family the father of the family has said that his child does not get vaccinated, usually we call on the bajenu gox, who will discuss with the father of the family to convince him, because a single unvaccinated child can constitute a danger for the others.”

Health region communication officer

School outreach activities

Schools play a special role in supporting immunization. From the national to the community levels, the MSAS and the Ministry of Education work together to increase public awareness of vaccines and other health-related topics. Schools are often used for vaccination outreach sites, and are also involved in political, health, education, and environmental issues. Teachers learn about the importance of immunization during their initial training. They share information about immunization with their pupils, who in turn relate it to their families.

“The school governments involve the students more and more in high decision-making instances such as the political governments, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Environment. Almost every school has the same organization. As far as vaccination is concerned, we very often involve the school governments to better sensitize their fathers.”

- Government staff, national level

Media engagement

The MSAS also uses media to ensure that the public has access to accurate information about vaccines. Senegal’s Association of Journalists for Health (AJSP) organizes press caravans to disseminate health information. While visiting communities, they also speak with community members and CHWs to further understand successes and challenges at the community level. MSAS helps to train these journalists and provides authoritative information and resources. Community radio stations provide free airtime for health-focused programming. MSAS staff visit radio offices or meet with media representatives to share accurate and relevant information.

According to key informants, social media has an overall positive impact on demand, especially in peri-urban areas and areas with higher levels of household income. Because access to cell phones and internet has increased in recent years, some national-level stakeholders now believe that social media outlets and internet resources are more effective than radio.

Combating misinformation and hesitancy

Misinformation related to vaccines spreads through community networks or social media. Assertions can be made that vaccines decrease fertility and are intended to control population growth; cause adverse effects, including sickness or death; or are against religious or cultural beliefs.

Senegal has addressed rumors and misinformation in multiple ways:

- ACPPs and community actors are trained to respond to rumors and are provided with materials for addressing and correcting misinformation. Chiefs and religious leaders also help in addressing rumors and misinformation.

- Community groups were created to identify which rumors were circulating in their communities. At community dialogue meetings, communities share knowledge and beliefs related to immunization. Any misinformation is corrected by trained community members, health workers, and volunteers.

- At the health-district level, the chief medical officer, health education manager, and district staff address rumors that cannot be resolved at the health post level.

- Journalists also address rumors and misinformation through their reporting.

Hesitancy may be greater among some ethnic groups. For example, key informants noted that the members of the Fulani ethnic group are reluctant to vaccinate their children. Many of the Fulani are nomadic, and thus are not always present in a community for vaccination outreach or communication events. Strategies to overcome hesitancy among the Fulani included communicating with families in their native dialect and engaging Fulani women as relais.