Six million women from the world’s poorest communities subsidizing delivery of essential health care, researchers say

A new report by Women in Global Health shows how health systems rely on women working for free or for extremely low pay to deliver essential health care

A new report by Women in Global Health highlights how many health systems are dependent upon women from the world's poorest communities working for free or for extremely low pay to deliver essential health care.

Six million women “work unpaid and underpaid in core health systems roles, effectively subsidizing global health with their unpaid and underpaid labor,” states the report. “Typically, these women are from low-income families, with limited education, working as community health workers (CHWs) in their local communities.”

“One point common to all is that the hours they spend on unpaid work add to the burden of work they already have and displace the opportunities for rest or other income generating activities,” write the authors. “This entrenches gender inequality, as women do more unpaid work, earn less than men on average and own fewer assets, and this adds to women’s disproportionate poverty throughout their lives.”

Women currently make up 70 percent of the globe’s health workforce and 90 percent of its patient-facing roles. However, women are overrepresented in the unpaid and low-paying health care jobs and underrepresented in leadership roles. For example, women make up only 3.7 percent of the CEOs of Fortune 500 health care companies, 31 percent of ministers of health, but 70 percent of the health and social workforce and 90 percent of the long-term health care workforce.

That women are over-represented across low paying health care jobs has created one of the highest gender wage gaps in any sector – 24 percent. This figure does not include the millions of women who work as unpaid community health workers or community health volunteers. COVID-19 exacerbated this problem since many frontline health workers, a majority of whom are women, were asked to work even longer hours for little or no pay.

Paying women fairly for their labor would provide a triple dividend said Ann Keeling, a senior fellow at Women in Global Health. “It would provide a health dividend by making health systems stronger, improving health outcomes, and saving lives. It would provide a gender dividend by bringing more women into formal jobs and strengthening their autonomy. And it would provide a development dividend because these jobs, when formalized and properly compensated, can help drive economic growth.”

Bangladesh and Ethiopia are examples, said Keeling, of how low-income countries can strengthen their health systems and improve women’s standing in their communities, in part, through better compensating the women who serve in frontline community-based health workers. Doing so can be cost-effective, said Keeling. For example, Bangladesh’s CHWs helped the country achieve a majority of its health-related Millennium Development Goals, including reducing under-five mortality by 75 percent, infant mortality by 72 percent, neonatal mortality by 65 percent, and the maternal mortality ratio by 71 percent. Contraceptive prevalence rate among rural women has increased by a factor of 10 from the 1970s to today, and immunization rates of DTP3 increased from near zero in the 1980s to more than 90 percent today.

“Better supporting frontline health workers can take the heat off the health system overall,” said Keeling. “For example, by catching diabetes early when it can be managed, so the patient doesn’t shows up in the hospital with kidney failure or in need of a limb amputation.”

The report noted that unpaid and underpaid health workers tend to have higher attrition rates. This impacts access to, the delivery of, and the costs of health care in profound ways. Exemplars research has found that high turnover rates can undermine the quality of health care provided because newer CHWs don’t have experience. High turnover can create high vacancy rates as governments can struggle to replace existing health care workers, creating a shortage of CHWs and reducing access to care. And high turnover rates increase costs, as training CHWs is a significant investment.

Those most impacted by the high turnover rates of frontline health workers are other women in need of health care. “Studies of and interviews with women working unpaid and grossly underpaid in health systems have shown that their responsibilities and tasks are typically focused on maternal, reproductive, and child health through reaching women in communities,” states the report.

These are among the reasons that the WHO’s 2018 Guideline on Health Policy and System Support to Optimize CHW Programmes strongly recommends “remunerating practicing CHWs for their work with a financial package commensurate with the job demands, complexity, number of hours, training and roles that they undertake.”

But the issue of paying CHWs is complex. As a recent article in the Journal of Global Health by Madeleine Ballard and her coauthors noted, “As the discussion evolves from whether to financially remunerate CHWs to how to do so, there is an urgent need to better understand the types of CHW payment models and their implications.”

For example, paying fair salaries to CHWs may require setting minimum standards for their education – which many women may not be able to meet. Likewise, research shows that when rural employment opportunities are compensated, they become more attractive to men who may push women out of the field. Liberia is currently working with Last Mile Health to help ensure that women are more heavily represented in the country’s formalized and professional rural CHW program.

Pakistan’s 100,000 Lady Health workers, a program launched in 1994, went on strike during the pandemic to protest their lack of pay, job security, and career pathways, as well as ongoing harassment they experienced while on the job – especially while promoting and delivering polio vaccinations.

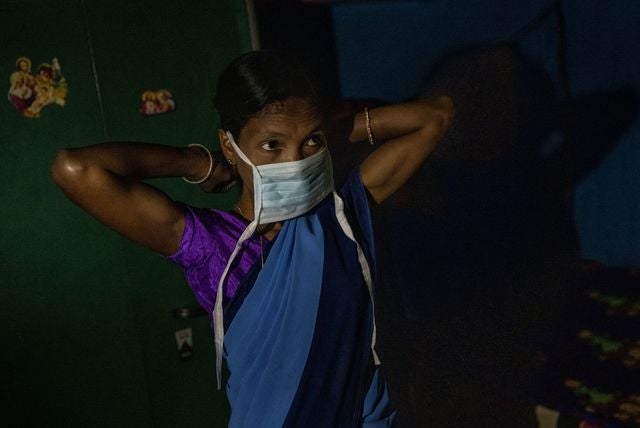

India’s one million ASHA workers are now collaborating with trade unions. The frontline health workers receive honorariums but are demanding salaries that reflect the country’s minimum wage laws as they are currently serving as the backbone of the country’s COVID vaccination effort.

What's more, where women are paid, often payments are not timely. Some CHWs report waiting months to collect their earnings.

Still, many women in India and beyond stay in such positions for years. Sometimes they report that the position gives them more freedom of movement than they would otherwise enjoy, access to training and education, and greater respect in the community. Indeed, many of the women report that they are seen as leaders in their community.

India has responded to the women’s demands thus far by helping ASHA workers complete their secondary school education if they have not already, and giving them preferential access to nursing school. “This is a win-win situation,” said Keeling. “It helps these women and their communities, but it also helps reduce the shortage of nurses.”

The report includes 10 recommendations, including calling on governments to fulfill their commitments to end unpaid work; following the WHO’s 2018 guidelines for CHWs, and the International Labor Organization's 5R Framework for Decent Care Work; and offering a career path that allows unpaid workers in the health system to train for formal roles in health care. Once WHO guidelines are met and CHWs have the right systems and support in place, governments have the opportunity to optimize CHW performance and impact, it said.

How can we help you?

believes that the quickest path to improving health outcomes to identify positive outliers in health and help leaders implement lessons in their own countries.

With our network of in-country and cross-country partners, we research countries that have made extraordinary progress in important health outcomes and share actionable lessons with public health decisionmakers.

Our research can support you to learn about a new issue, design a new policy, or implement a new program by providing context-specific recommendations rooted in Exemplar findings. Our decision-support offerings include courses, workshops, peer-to-peer collaboration support, tailored analyses, and sub-national research.

If you'd like to find out more about how we could help you, please click . Please consider so you never miss new insights from Exemplar countries. You can also follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn.