Gender

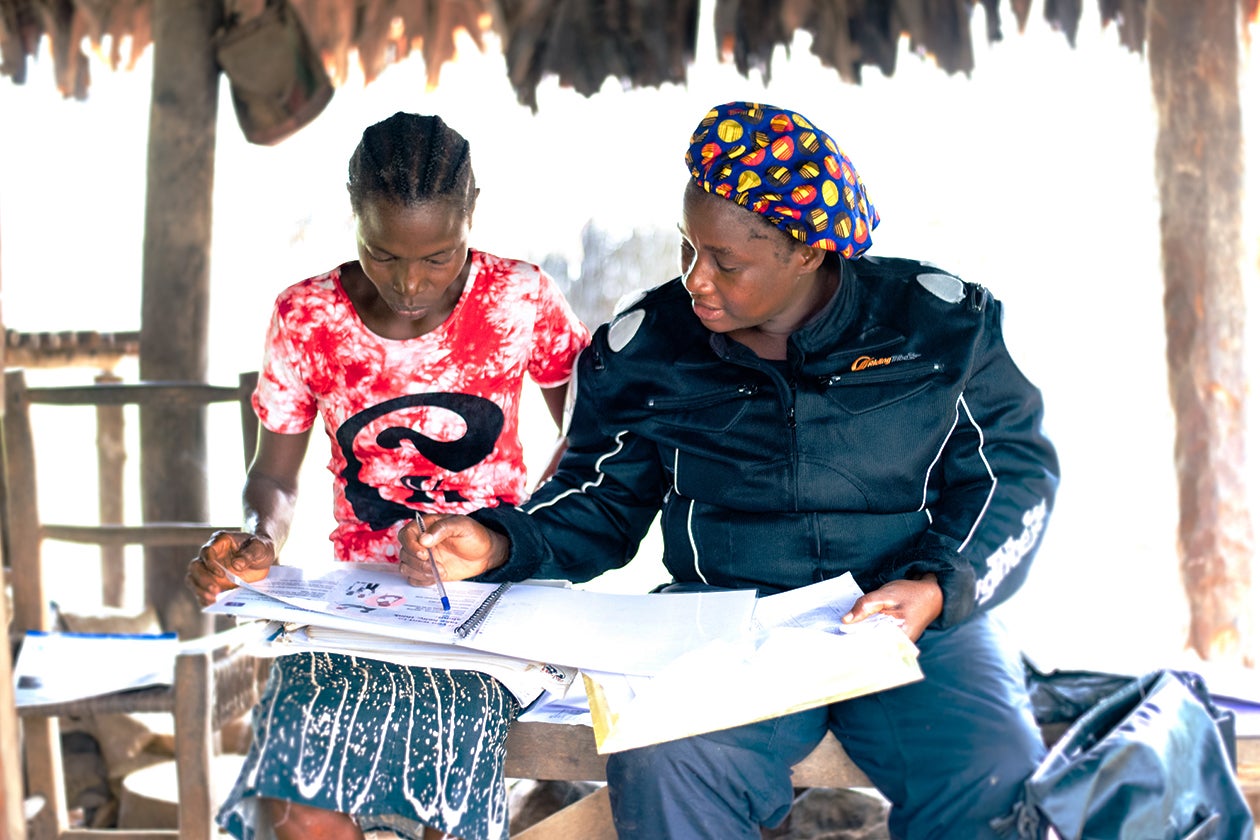

Despite the policy preference for female community health workers (CHWs), Liberia’s CHWs are disproportionately male. As of May 2019, only 17 percent of CHWs were women.

Literacy levels may be one of the barriers that has prevented the successful recruitment of female CHWs.

While global evidence is mixed, there is concern that male CHWs in Liberia may discourage use of health services for women – especially family planning services.

In light of this concern, finding other ways to incorporate more women in this workforce will likely be an issue discussed further, as the government begins to review progress on its community health policy. (The Ministry of Health intends to conduct a comprehensive review of the progress and challenges of the community health policy in 2020.)

Uneven implementation

When Liberia’s Ministry of Health adopted its 2015 Community Health Policy and Strategic Plan, its goal was to create a single, consistent, and unified CHW program across all 15 counties of Liberia, a stark contrast from the previous fragmented community health volunteer system.

Despite developing a new standard policy and standard program design, Liberia’s monitoring mechanisms have still documented variations across a wide range of important practices including supervisor performance, CHW knowledge and performance, and supply chain management.

Broadly speaking, these variations in CHW knowledge and performance are believed to be the result of several factors, including the overall quality and quantity of capacity-building support provided at local and county levels, how long the program has been implemented in a given county, a geography’s proximity to the national capital, overall county level investment priorities and health sector resources, and subnational variation in literacy rates and educational attainment.

The data systems that identified these performance and implementation challenges are being harnessed to prioritize areas and individuals for support and alignment. However, most of these systems, like the Community Based Information System (CBIS) and Implementation Fidelity Initiative (IFI), were only developed since program launch in 2016. The program also needs to continue strengthening the consistency, quality, and use of this data.

Supervision – Consistency in reporting

The percentage of supervisors in each county who submitted their monthly service report for three consecutive months between July 2017 and August 2019 ranged from fewer than 50 percent in Grand Cape Mount County to 100 percent in Margibi and Maryland counties. This could indicate supervisors are not regularly visiting their CHWs each month, or CHWs are not consistently providing the required data, or supervisors are not motivated to write and submit their monthly reports.

Payments

Timely payment of CHWs across all counties remains a challenge. In a few counties, CHWs went more than six months without payment in 2019 due to management issues.

Delays in payment happen for several reasons. For example, in counties supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), CHWs do not receive payment until they submit their monthly reports – often causing a delay. Whereas in other counties supported by the Global Fund, payment of CHWs tends to be more timely because they use mobile payment methods and complete payment regardless of CHW reporting.

The Ministry of Health aims to address these payment challenges. Potential solutions that the Ministry of Health may explore are streamlining payment methods and learning from the success of mobile money, restructuring donor funding in counties where multiple donors exist to enable easier payment tracking, harmonizing payment protocols, and establishing a payment tracker.

Implementation Fidelity Initiative

| INDICATORS | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|

Community level | ||

% of CHAs with restock last month | 42.6% | 45.1% |

% of CHAs visiting all five households | 83.2% | 86.1% |

% of CHAs answering all four service delivery questions correctly | 28.5% | 37.7% |

% of CHAs with 1+ CHSS visits in last month | 94.7% | 88.9% |

% of CHAs with 2+ CHSS visits in last month | 85.8% | 80.0% |

% of communities where CHC had 1+ meeting in the past month | 74.3% | 72.6% |

% of CHAs receiving CORRECT incentive | 79.4% | 67.2% |

% of CHAs receiving ON TIME incentive | 44.7% | 22.4% |

% of CHAs receiving CORRECT and ON TIME incentive | 43.4% | 22.4% |

Facility level | ||

% of CHSSs who spent the appropriate time in the community vs facility | 50.4% | 68.4% |

% of facilities that conducted a health demonstration in the past month | 97.5% | 97.4% |

% of CHSSs conducted supervision as planned | 37.4% | 49.6% |

% of facilities where CHSS reports were submitted on time for 3 months | 87.2% | 93.2% |

% of CHSSs receiving CORRECT incentive | 72.4% | 66.7% |

% of CHSSs receiving ON TIME incentive | 45.2% | 24.4% |

% of CHSSs receiving CORRECT and ON TIME incentive | 42.5% | 22.8% |

Data source: Ministry of Health

Supply chain

The availability of lifesaving drugs varies significantly by county, and stock outs are a symptom of challenges at all levels of Liberia’s drug supply chain. At the national level, Liberia’s supply chain management system faces difficulties in forecasting demand, monitoring storage levels at central warehousing, managing inventory, managing transportation and distribution from central to county to district levels, and handling overall coordination of the supply chain. At the county level, supply chain challenges include inadequate storage space, warehousing practices, and lack of equipment for last-mile distribution. Floods or heavy rainfall that wash out roads regularly or make them otherwise impassable, sometimes for months at a stretch, also pose challenges to a well-functioning supply chain at the local level.

The percentage of CHWs with critical lifesaving supplies in stock is generally low according to Implementation Fidelity Initiative data. In 2018 and 2019, fewer than half of CHWs had stocks of zinc to stop diarrhea or the antibiotic amoxicillin. Just over half of CHWs had oral rehydration solution and malaria drugs. The 2017 diagnostic of facility level stock, found that 53 percent of essential medicines were in stock.

These stock-outs of critical supplies for CHWs remain a significant barrier to success.

| COMMUNITY LEVEL | FACILITY LEVEL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | |

Microlut | 45.3% | 43.0% | 68.3% | 51.7% |

Microgynon | 33.0% | 25.2% | 56.0% | 33.3% |

ACT 25 | 61.9% | 57.9% | 60.6% | 52.5% |

ACT 50 | 65.3% | 54.5% | 72.2% | 39.0% |

Artesunate | 3.9% | 4.6% | 7.9% | 3.3% |

Amoxicillin | 43.3% | 35.6% | 50.4% | 30.1% |

ORS | 61.1% | 60.4% | 63.2% | 57.7% |

Zinc | 31.2% | 44.4% | 31.7% | 33.3% |

Paracetamol | 50.0% | 45.2% | 63.8% | 36.1% |

RDT | 66.5% | 72.6 | 74.4% | 66.4% |

Male condom | 67.8% | 64.4% | 79.4% | 69.2% |

Data source: Ministry of Health

Part of the supply chain challenge in Liberia is that many of the commodities are procured and supplied by different organizations. For example, Global Fund and the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative provides malaria drugs to all counties, whereas UNICEF provides drugs to County Health Teams for acute respiratory infection and diarrhea, but only in Liberia’s five southeast counties. In the other ten counties, drugs for acute respiratory infection are generally provided by Chemonics with funding from USAID. Such a siloed approach leads to redundancies and inefficiencies in both procurement and delivery.

In 2017, Liberia launched the Logistics Management Information System (LMIS) to track and validate supply chain data in order to improve management. However, as of 2019, Liberia’s LMIS system is not fully functional. Data systems to track medicine remain opaque, poorly documented, and inconsistently followed. The government is working to strengthen the LMIS by establishing county supply chain technical working groups to identify gaps and align with the central Ministry of Health to address them.

In an effort to improve supply chain management, Liberia consolidated its patchwork of warehouses into a single modern warehouse in 2018, which has brought about further challenges. In 2019, the country experienced widespread stock outs of medicines, illustrating the double-edged sword of a unified national system.

County-level capacity for program management

The government’s long-term vision is that national and county governments will fully own and manage the CHW program. However, Liberia’s 15 counties currently vary in their capacity to effectively manage the program. Some County Health Teams lack technical expertise related to monitoring and evaluation, and others have limited expertise in evaluating CHW supervision.

In 2018, the Community Health Services Division, which is responsible for setting standards, developing policy, and coordinating community health programs nationally and collaborating with County Health Teams, conducted assessments of the capacity of County Health Teams to implement the CHW program. As of mid-2019, partners including USAID and several nongovernmental organizations are developing a process to institutionalize routine assessments and follow-up plans for strengthening the capacity of County Health Teams. The assessments, which occur at least every two years, involve visits to County Health Teams, interviews with staff, and review of records. Each County Health Team’s management ability is evaluated and scored based on the following criteria:

| IDEAL PRACTICE OF COUNTY HEALTH TEAM |

|---|

Has an annual operational plan that includes activities to implement national CHW program. |

Can communicate and share best practices with the central Ministry of Health and with other County Health Teams. |

Has clear system to allow information regarding national CHW program to flow from the management to the community levels, and vice versa. |

Has a clear system to communicate with health facilities. |

Has a clear system to communicate with partners. |

Staff are oriented and have access to all standard operating procedures and documents related to the national CHW program (e.g., National Community Health Strategic Plan, National Community Health Policy, National Community Health Assistant Supply Chain Standard Operating Procedures, Community-Based Information System Standard Operating Procedures, and the National Community Health Assistant Training Standard Operating Procedures). |

Submits regular and timely reports concerning the national CHW program. |

Data source for table: Liberia Ministry of Health

Expanding reforms to peri-urban and urban settings

The CHW program was designed to be implemented only in remote communities more than five kilometers from a health facility. In communities within five kilometers of a health facility (mostly those in peri-urban and urban areas) community health volunteers and other health care providers still provide health services. In some peri-urban and urban areas, these cohorts are uncoordinated and not well-trained, and the differentiated services provided by each cohort imposes additional management, financial, and oversight requirements at the county and national levels. The Ministry of Health is exploring ways to consolidate and streamline these cohorts to create a unified national community health system, with standards of service and care that are universally integrated and extend coverage to all Liberians, using the same data, financial, and operational systems.

Adapting service offerings to meet evolving health needs

In some cases, the services provided by CHWs do not match the needs of the community. For example, family planning coverage remains low in Liberia, with only 21.7 percent of family planning needs met nationally, and just 17.3 percent in rural areas.

Family Planning Coverage in Liberia 2014

Yet the government has not supported the national rollout of Sayana Press, a long-acting, discreet, and much sought-after reversible contraceptive. Instead, CHWs offer female condoms, which are extremely unpopular.

Likewise, immunization coverage in rural and remote areas remains low. For example, diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis coverage in rural Grand Gedeh County in 2015 was 21.2 percent, with periodic outbreaks of measles, pertussis, and other vaccine-preventable illnesses. The CHA Program has not fully leveraged CHWs to address immunization, even if CHWs do support immunization campaigns. Gavi and MOH are currently developing programming to strengthen immunization support by CHWs.

Finally, CHWs could play larger roles in the testing and treatment of tuberculosis and HIV, both challenges in rural Liberia. The Ministry of Health has begun conversations about how it might use CHWs to increase uptake of testing and treatment for these diseases.

Long-term financing

In Liberia’s current domestic political and donor environment, long-term financial planning remains a challenge. The government has engaged in detailed mapping of timelines and agendas and has contributed to overarching donor policy frameworks (such as the World Bank’s Country Partnership Framework or USAID’s Country Development Cooperation Strategy) to identify potential funding.

Amidst the Ebola crisis, donors pledged a total of $1.3 billion – about ten times the amount of Liberia’s annual development assistance – at the July 2015 International Ebola Recovery Conference. Some of this funding was intended for strengthening Liberia’s health workforce. Liberia’s CHW program has benefited tremendously from this Ebola funding, but as of late 2018, only 31.5 percent of the money pledged to Liberia has been disbursed.

Looking ahead, there is even greater uncertainty. From 2019 to 2025, roughly half the necessary funding remains uncommitted over the next five years, as illustrated below (data excerpted from an investment case made in late 2018). However, several donors (including USAID and the Global Fund) are expected to consider renewing commitments to the CHW program as their current grants come to an end. The Ministry of Health is expected to advocate for renewed commitment during these donor funding cycles.

Funding shortfall: total projected expenses and funding for national CHW (community health assistant) program

Ministry of Health of Liberia. The Liberian Community Health Assistant Coalition Investment Prospectus. Monrovia: Ministry of Health; June 2018.