In Zambia, research identified three ways (or pathways) through which reforms have over time improved PHC outcomes. This third pathway enabled close-to-community service delivery by improving access to care, facility readiness, and outreach-based service delivery models. The following sections reflect the main themes comprising this pathway.

Key Points

Primary health care (PHC) reforms in Zambia focused on facilitating care delivery and improving community access to health services and outreach for prevention nationwide.

Zambia prioritized equitable access to health care for the poorest communities by decreasing financial barriers to care and calibrating district funding flows to ensure they reflect local poverty levels.

A key pillar of Zambia’s efforts to improve health system access and equity was the effort to decrease geographic barriers to care by expanding PHC infrastructure, especially in rural areas. Between 2005 and 2017, the number of health facilities in the country more than doubled.

Public and community outreach and prevention activities, especially in rural areas, helped meet the Vision 2030 commitment to “equitable access to health care for all.” Study districts allocate 50% to 60% of funds.

Equitable access to health care for all

In 2006, the Zambian government published a report called Vision 2030: A Prosperous Middle-Income Nation by 2030 to guide future development efforts nationwide. The report covers economic development, income inequality, sanitation, education, and health. “Equitable access to quality health care to all [Zambians] by 2030,” the report explains, means stopping the spread of tuberculosis, malaria, and HIV; increasing health spending per capita; improving public programs related to maternal and infant care, family planning, and HIV/AIDS; building more health facilities; and increasing human resources for health. The report lists five health goals for the next quarter-century:

- Reduce the under-five mortality rate

- Reduce the maternal mortality rate

- Increase the proportion of rural households living within 5 kilometers of a health facility (in 2006, this proportion was 50%; the Vision 2030 goal is 80%)

- Reduce the population-to-doctor ratio

- Reduce the population-to-nurse ratio

Since the publication of that report, PHC strengthening in Zambia has focused on expanding geographic and financial access to the health services that earlier rounds of reform made possible.

Essential health benefits and the elimination of financial barriers to access

Between 1993 and 1996, Zambia’s Ministry of Health developed the country’s first “Basic Health Care Package” (BHCP), a list of essential PHC services policymakers believed would have the greatest and most cost-effective impact on the country’s most serious health problems. Interventions included in the BHCP were selected for the “diseases and conditions that cause the highest burden of disease and death.” Policymakers also believed the services on the list could be delivered equitably to people in every region of the country.

The Ministry of Health also identified 10 national health priorities, initially selected on the basis of epidemiological burden:

- Child health and nutrition: to reduce the mortality rate among children under five

- Integrated reproductive health: to reduce the maternal mortality ratio

- HIV and AIDS, [tuberculosis], and [sexually transmitted diseases]: to halt and begin to reduce the spread of HIV, [tuberculosis], and [sexually transmitted diseases] through effective interventions

- Malaria: to reduce incidence and mortality caused by malaria

- Epidemics: to improve public health surveillance and control of epidemics

- Hygiene, sanitation, and safer water: to promote and implement appropriate interventions aimed at improving hygiene and access to acceptable sanitation and safer water

- Human resources: to train, recruit, and retain appropriate and adequate staff at all levels

- Essential drugs and medical supplies: to ensure availability of essential drugs and medical supplies at all levels

- Infrastructure and equipment: to ensure availability of appropriate infrastructure and equipment at all levels

- Systems strengthening: to strengthen existing operational systems, financing mechanisms, and governance arrangements for effective delivery of health services

The process of defining the Essential Health Benefits package played a key role in shaping health policy. It also highlighted how cost-effective it could be to invest in PHC interventions, particularly prevention, which led to a commitment to dedicate 60% of health funds to districts for PHC delivery. (On average, since 2000, Zambia has allocated 40%–45% of total health expenditures to PHC.)

From the beginning of the process of implementing PHC in Zambia, policymakers designed reforms to make care affordable and accessible to as many people as possible.

Health care access

Between 1964 and 1991, health care was free in Zambia. After that, the government introduced a system of out-of-pocket fees for primary care and other services. However, in 2006, the government began to abolish those fees for primary health services (including provider visits, drugs, and laboratory services) at public facilities in rural areas. The policy was expanded to cover facilities in peri-urban areas in 2008 and was adopted nationwide in 2011. Since then, primary care in Zambia’s government health facilities—which includes all health services provided at public clinics, rural community health posts, urban and rural health centers, and district hospitals —is officially free at the point of use. (Particularly in rural areas, the role of the private sector in PHC delivery is limited.)

The reform was implemented by both injecting more funds into the system to supplement the income loss from facilities no longer collecting fees to pay for services and adjusted the mechanism by which funds flowed centrally down to health facilities. It earmarked monthly grants from districts to facilities that were linked to actual utilization of health care services - based on projected income loss from the removal of user fees. Initial funds injections came from the United Kingdom's development assistance agency (called DFID at the time).

At about the same time, between 1995 and 2020, Zambia’s reliance on out-of-pocket spending—which falls on patients and can be catastrophic in emergencies—has fallen, from an estimated 38.6% of overall spending in 1995 to 9.0% in 2020.

Evidence on whether the elimination of user fees increased PHC utilization, directly improved health outcomes in Zambia, or both is mixed. ,, However, researchers believe the policy change improved financial protection by reducing direct medical expenditures and encouraging patients to use health facilities in the public sector.,

Needs-based allocation

In 1994, the Ministry of Health implemented a formula for distributing health funds to districts that was based on population size and the number of hospital beds per district, and which resulted in relatively equal per capita funding., However, Zambians in smaller and more rural districts argued that this formula disadvantaged them and their communities, especially considering user fees from larger and wealthier districts. According to health officials, “user fee collections amounted to 7%–10% of total income in some of the larger districts; in contrast, they were typically less than 3% in the poorer districts.”

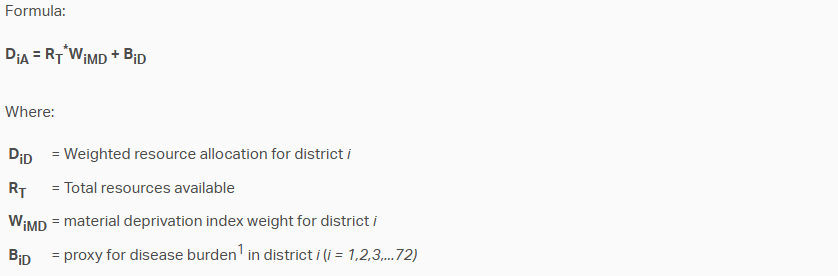

To develop a more equitable and responsive process for resource allocation in a country with enormous infrastructure imbalances—especially between urban and rural districts—in 2004 the Central Board of Health and Ministry of Health developed a “deprivation matrix” to rank all of Zambia’s districts according to demographic, health, poverty, and other measures of material need. The formula was also intended to prioritize PHC and lower-level health facilities by ensuring that second- and third-level hospitals, usually located in more affluent urban areas, would not monopolize scarce resources. Officials use this formula to inform the allocation and disbursement of district cash transfers to the highest-need communities and facilities.

The resource allocation formula was based on an index calculated using material deprivation data from several sources. These included the Census, Living Conditions Monitoring Surveys, and the HMIS. Measures included percentage of households that did not have access to basic goods and services (sanitation, transport, energy, refrigeration), basic demographics and incidence and fatality rates from selected conditions.

Expanded physical infrastructure for PHC

A key pillar of Zambia’s strategy for improving equitable access to PHC in response to the Vision 2030 report was the expansion of the country’s PHC infrastructure, especially in underserved rural and remote areas. Increasing the proportion of Zambians living within 5 kilometers of a health facility from 50% to 80% meant building more of them. Zambia’s 2017 Health Facility Census found that between 2005 and 2017, the density of health posts delivering PHC to rural populations nationwide increased from eight to 61 per 10,000 people. The 2005 Zambian Health Facility Census found 1,369 health facilities in the country. By 2017, that number had almost doubled to 2,650.

According to Zambia’s Ministry of Health, all this construction increased the proportion of rural households living within 5 kilometers of the nearest health facility to 79% in 2016, meeting the 2030 target nearly 15 years early.

Over that same period, travel time to the nearest facility offering under-five immunization substantially decreased. In 2000, 21% of children younger than one lived within a half-hour walk of the nearest health facility. In 2017, 34% did. (See Figure 12)

Figure 12: Community access: Travel time to closest facility with routine immunization services

At the same time, DTP3 coverage increased from 78% to 91%. (See Figure 13)

Figure 13: DTP3 Coverage: Percent of 11-23 month-olds with three doses of DTP

has found that the expansion of Zambia’s cold chain and refrigeration infrastructure likely played a important role in improving immunization and vaccine coverage.

Community outreach

After they had consolidated the governance and financing reforms of the early 1990s, Zambian health officials leveraged traditional community-led approaches to planning and oversight to build a grassroots, district-level essential services platform for cost-effective PHC delivery. In 1999, they established semiannual Child Health Weeks for high-impact basic health services such as immunization, nutritional supplementation, and deworming. Throughout the 2000s, the range of services offered at the community level grew to include counseling and testing for HIV and surveillance for cholera, polio, and Ebola virus disease. Zambia adapted this community care platform for international initiatives such as the Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses strategy and malaria community case management., More recently, health officials used it to conduct COVID-19 education and vaccination campaigns.