In Zambia, research identified three ways (or pathways) through which reforms have over time improved PHC outcomes. This second pathway improved staff productivity and attitude through incentives, particularly for community health workers. The following sections reflect the main themes comprising this pathway.

Key Points

When Zambia had established foundations for health system governance and financing, policymakers turned their attention to improving access to primary health care (PHC) services nationwide by supporting health workers, both improving their working conditions and increasing their numbers.

Improved processes for strategic planning set targets for closing the country’s PHC coverage gap and identified data-driven targets to measure and track health workers’ performance. At the same time, financial and nonfinancial incentives aimed to improve staff productivity and reduce overwork and overcrowding in health facilities.

Starting in 2003, a Health Worker Retention Scheme incentivized the geographic distribution of health workers and decreased absenteeism.

Since 2010, a cadre of formally trained and remunerated community health assistants (CHAs) conducts primary health care outreach activities nationwide, and their outreach has helped increase PHC utilization at the district level.

Community-based approaches to care delivery

Since Zambia's Ministry of Health published the country's first National Health Strategic Plan in 1994, officials have sought to "provide Zambians with equity of access to cost-effective quality health care as close to the family as possible."

This community-based approach to care delivery requires more health workers, especially in rural areas. At the beginning of the study period, Zambia had been experiencing a severe shortage of health workers, due in part to a "brain drain" of educated and skilled health workers to neighboring countries and overseas. The governance and financing reforms the Zambian health system introduced in the 1990s improved coordination and planning at all levels of the system. However, they did not address the country's chronic shortage of health workers. According to its 2005 Human Resources for Health Strategic Plan, Zambia had just half the number of health workers it needed to provide basic health services-a shortage of nearly 30,000 workers. Moreover, regional staffing imbalances made that gap much more acute in rural areas.,

By 2023, Zambia's combined density of doctors, nurses, and midwives was 15 per 10,000 population, compared to 8 per 10,000 in 2011. This was done as part of the government's effort to increase the number of positions on their payroll and introduce incentives to try and improve geographical distribution of the healthcare workforce.

Support for Zambia's health workers

Starting in the late 1990s, health officials began to implement reforms aimed at enabling the delivery of key PHC interventions and outreach by supporting the health workforce. They later accelerated these efforts as a way to meet one of the long-term goals in 2006's Vision 2030 national development plan: "provide equitable access and health care to all.",

Incentive schemes for health workers

Along with staff shortages and geographic maldistribution, health officials in the early 2000s reported high rates of absenteeism and low staff morale, which they attributed to high workload and low-and sometimes delayed, reduced, and withheld-pay. (Ten percent of staff in one survey even reported having to pay a "facilitation fee" to receive their salaries.) In 2003, in partnership with the government of the Netherlands, Zambian health officials launched a Health Workers Retention Scheme (HWRS) to recruit skilled clinical staff to rural and remote areas and to reduce their attrition. The HWRS included a range of financial and nonfinancial incentives for doctors working outside urban areas, including:

- A monthly hardship allowance (higher for those in rural and extremely rural districts)

- Education allowances for health workers’ children

- Housing and funds for housing rehabilitation

- Vehicle loans

- Communications equipment, including solar panels, boreholes, and radios

Opportunities for career and professional development,,, In 2007, the HWRS expanded to include nurses and other clinical staff such as environmental health technicians, medical teaching staff, and medical consultants.

However, early studies showed that the HWRS incentives had not improved health worker retention in rural areas. In 2014, health officials launched a strategy to increase the program's sustainability, tweaking the nonmonetary incentives they offered to appeal to more health workers. Improved housing in rural areas, education incentives, and improvements to rural health facilities all proved successful in nudging health workers to choose jobs in rural districts.

Since 2015, Zambia has seen a steady increase in the availability and geographic distribution of doctors and nurses nationwide. (See Figure 9.)

Figure 9: Doctors and nurses density per 10,000 population

A 2016 analysis found that nearly half of the country’s doctors, nurses, midwives, and other clinical staff were working in rural areas,, and remuneration for clinical staff has been more timely and consistent in recent years.

Read more about recent challenges in staff shortages and retention.

Community health assistants

In 2010, Zambia's Ministry of Health introduced a new cadre of community health workers that are formally trained and remunerated, called the Community Health Assistants (CHAs). The program's intent was to support doctors, nurses and other clinical staff; enable task-shifting; improve the geographic distribution of the health workforce; make community health workers a regular part of the national health strategy; and boost local outreach services., A pilot program, which trained 307 CHAs, ran from 2011 until 2013.,

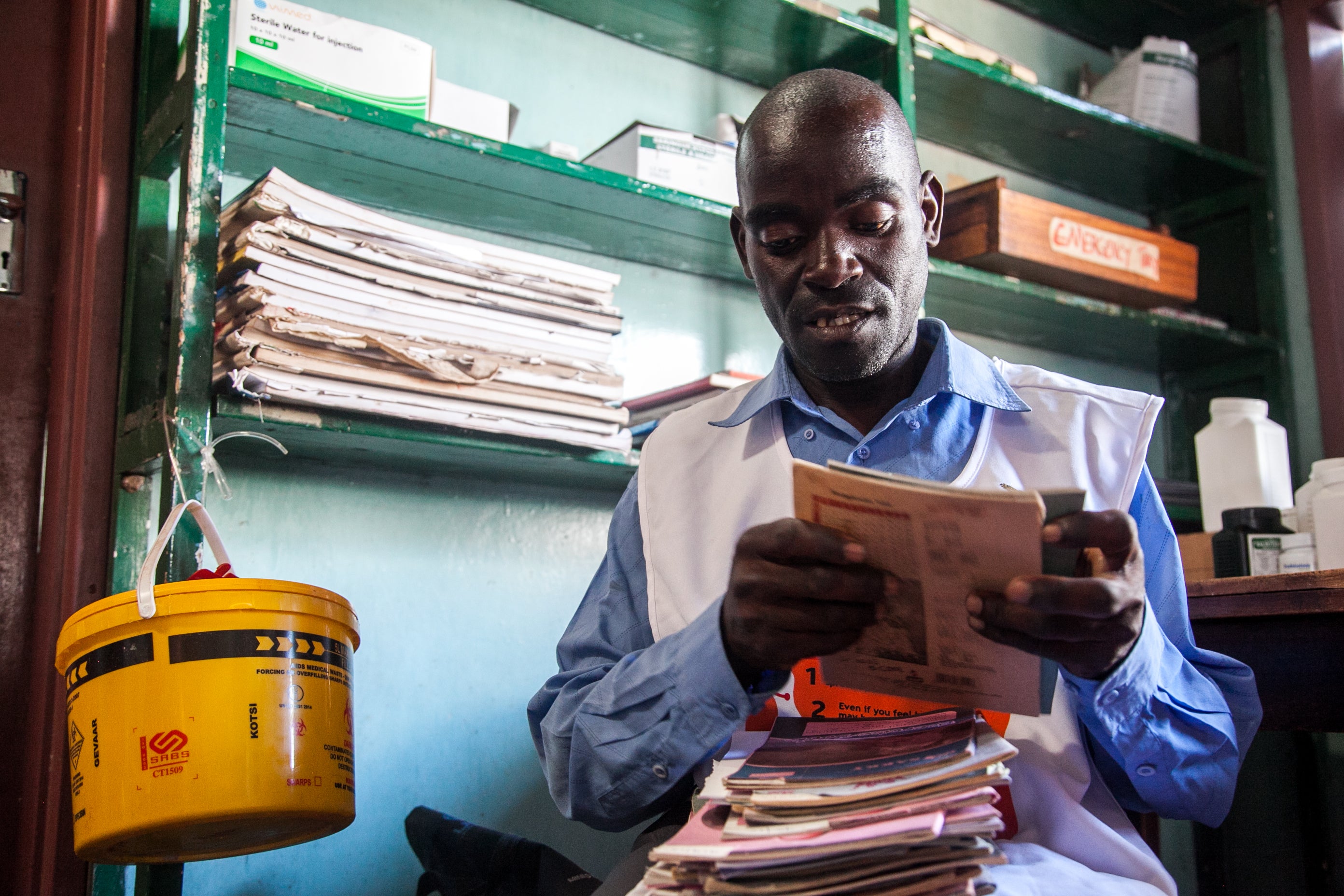

There are two forms of community health workers in Zambia. CHAs, are on the government payroll and should receive a consistent stipend as well as other civil servant benefits.,, By contrast, community health volunteers receive short, ad hoc training and work as volunteers on programs run by NGOs., CHAs are high school graduates chosen by their Neighborhood Health Committees and District Health Management Teams to receive a year of standardized training (covering preventive and curative care and strategies for health promotion) at an accredited Ministry of Health training school.

Trained CHAs return to their home communities, where they are expected to spend about 20% of their time at local health facilities performing services like immunization so that nurses can focus on more complicated tasks. When possible, however, they spend most of their time in the field-along with their diplomas, they should receive a uniform, a bicycle, and a mobile phone -working on outreach activities such as community education and health promotion as well as patient support. A full description of the services provided by CHAs is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Outreach services by community health assistants (CHAs)

Researchers report positive public perceptions of Zambia's CHA program, the CHAs themselves, and the quality of their training. This community support can help keep CHAs on the job despite funding challenges such as late (or nonexistent) salary payments. As of 2021, approximately one CHA for every 5,000 rural residents had been deployed in Zambia-but about half of those who completed training that year had not been added to the payroll because of a lack of funding.

At the district level, PHC utilization has increased as the CHA program ramped up. In the Zambezi district, for instance, there has been a substantial increase in the number of household visits to under-five children, pregnant women, people with HIV, and women of reproductive age for family planning, as well as in the number of community outreach events. (See Figure 11.)

Figure 11: Household visits reported by CHAs, Zambezi District