Key Points

Peru is a country of great cultural diversity, attributable in part to the varied terrain of a land stretching from the Pacific coast to the Andes to the Amazonian jungle.

The 2000–2015 study period saw both relative political stability and economic growth, as the country sought to find new footing after a long period of intense turmoil and violent insurgency.

Among the primary ways that Peru attempted to achieve greater social cohesion was through a series of anti-poverty accords, including the 2002 National Agreement.

Geography and Population

Peru is the third largest country in South America and has a highly diverse topography, with three distinct regions: the Pacific coast (including the country’s capital and largest city, Lima), the Andean highlands, and the Amazon rain forest.

Peru’s population grew steadily during the study period, from 26.5 million in 2000 to 30.5 million in 2015. The majority (52 percent) of the population resides in the coastal region, followed by the highlands (36 percent). Though rain forest makes up almost 60 percent of Peru’s land area, only 12 percent of the country’s people live there.

The rich geographic variety of Peru has contributed to a high level of cultural diversity. In 2017, indigenous people made up about 26 percent of the country’s total population. While a large majority of Peruvians speak Spanish, dozens of native languages remain. One of these, Quechua, is an official national language and is spoken by about 19 percent of the population.

The last several decades have seen increased urbanization. The percentage of the population residing in cities increased from 46.8 percent in 1960 to 64.6 percent in 1980, 73 percent in 2000, and 77.4 percent in 2015.

Political Profile

Peru gained its independence from Spain in 1821, and its national history has included long stretches of acute political instability.

The decades immediately preceding the study period were one such period of turmoil. In the 1980s, populist governments of Fernando Belaunde Terry and Alan García Pérez enacted policies that tended to worsen the country’s already troubled economy, which only abetted the rise of Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso), a Maoist guerrilla movement that was established in 1970.

The guerrilla and terrorist operations of Shining Path resulted in the deaths of about 70,000 people by the time its leaders were arrested and imprisoned in 1992. In addition to this direct death toll, Peru’s internal strife led to chronic political instability, continued economic crisis, and diminished access to health care services, particularly for the poor.

The Alberto Fujimori government, which subdued the Shining Path in the 1990s, ended in 2000 as Fujimori left office under human rights violation and corruption charges, for which he would eventually land in jail. In 2001, Alejandro Toledo became the country’s first elected Quechua president.

During the 2000–2015 study period, Peru underwent several leadership transitions and occasional periods of political unrest. However, it was also a time of increased commitment to the advancement of the country’s long-neglected development goals.

Contextual Factors Contributing to Success

Consistent National Leadership and Prioritization of Health and Poverty-Reduction Initiatives

One interviewee said that after the political crises of the 1990s, politicians began to deepen their consideration of how to bring lasting stability and progress.

He said, “A transitional government was installed in 2001, which asked a question that I think is substantial: ‘What is the Peru that we want in 20–30 years?’”

An initial answer to that question came in the form of the 2001 Roundtable for the Fight Against Poverty, which brought together senior business, political, religious, and social leaders to collect evidence on anti-poverty initiatives and ensure ongoing political support for such programs.

Several of the policies championed by the Roundtable have explicitly designated resources to reducing chronic child malnutrition and neonatal mortality. The Roundtable’s strong presence in national politics contributed to the development of programs that addressed social inequities, and specifically targeted the improvement of maternal and child health.

One interviewee credited the Roundtable for Peru’s achievements on the Millennium Development Goals, saying “the Roundtable has addressed the public policy discussion on [maternal and child health] issues and subsequently contributed to better mechanisms for cleaning up public policy in relation to mortality and in particular neonatal mortality.”

The Roundtable has established a trusted forum for keeping anti-poverty concerns on the national agenda. “I think that helps a lot as a country to have that permanent dialogue, which is available not only when it is required, but is [rather] a permanent interaction that helps fine-tune implementation models, and makes spending more transparent as well,” said another interviewee.

“The Roundtable is reviewing budget and implementation issues and looking at the problems that are in regions,” the interviewee added. “I think it also helps the same actors who execute to be able to feel observed and seen, and not just do what they want without accountability and transparency.”

A year after the formation of the Roundtable, a new National Agreement, the Acuerdo Nacional, committed Peru’s political parties to the strengthening of democracy and the promotion of social justice and equity – including the elimination of extreme poverty and the universal provision of health care.

The National Agreement has shown impressive staying power. Presidents elected after its signing have continued to adhere to certain specific priorities outlined in the document – notably including the funding of programs related to maternal and pediatric health; promotion of food security and nutrition; elimination of poverty; the attainment of specific goals for reducing child mortality; and the establishment of mechanisms for monitoring progress in these areas.

One of the most notable anti-poverty policies that Peru undertook during the study period was the Juntos (“together”) conditional cash transfer program, which provided financial assistance to the poor based upon participants’ use of maternal and child health services.

Juntos, formally known as the National Program of Direct Support to the Poorest, was created in April 2005 with approximately US$37 million in initial funding . As a long-term goal, it aimed to interrupt intergenerational transmission of poverty through improved access to education and health services.

The program originally targeted poor families with children under the age of 14, and by 2010 its aim broadened to all low-income households – as defined by a variety of metrics, including the literacy levels of women in the home, access to appliances and fuel sources, and the availability of public services.

Juntos provided a monthly cash transfer of 100 soles (approximately US$30), but this payment required families to seek basic routine health care visits and primary education for children. Children were also required to have a national identification document. In cases of noncompliance, transfers are suspended – for three months initially, or indefinitely for repeated violations.

Pregnant women participating in Juntos were required to attend antenatal care visits in alignment with the national protocol, which recommends at least six visits during pregnancy (for more details on this policy, see the article). Compliance with Juntos requirements was directly verified by health care providers and monitored by the program’s field staff every two months at health center visits.

Juntos was piloted in 110 districts of the Huancavelica, Ayacucho, Apurimac, and Huanuco regions beginning in September 2005, and expanded the following year into five new regions (Puno, Cajamarca, La Libertad, Junin, and Ancash), reaching a total of 210 new districts.

In 2007, the Ministry of Health (MOH) approved expansion into another 247 districts. By 2013, Juntos was implemented in more than 1,000 municipalities comprising about 60 percent of Peru’s total area. By the end of the study period in 2015, the program reached all municipalities classified as poor. As of 2016, Juntos covered 663,000 households in 1,247 of Peru’s 1,828 districts, reaching over 1.6 million children and adolescents.

Juntos and other anti-poverty initiatives achieved some important equity objectives. The population living below the poverty line substantially declined, and health outcome inequities related to income and geography narrowed substantially.

A 2009 study found that intensity of use of health services increased for children under five in households participating in Juntos. These children were 37 percent more likely to receive health checks, which included such vital basic services as vitamin A supplementation.

Economic Growth

As mentioned earlier, the decade preceding the study period was a time of severe turmoil for Peru, both political and economic. The country experienced the most severe inflation crisis in its history in 1990, as terrorists threatened production facilities and other economic targets.

By 1993, aided in part by the security and economic policies of the Fujimori government, Peru’s economy gradually began to recover. This momentum continued throughout the study period, with Peru’s gross domestic product (GDP) increasing from $170.1 billion in 2000 to $393.6 billion in 2017 (PPP constant 2011 international $). GDP per capita also increased, from $6,563 in 2000 to $12,237 in 2017 (PPP constant 2011 international $).

This growth was sufficiently robust to shift Peru’s status in the global economic order. While the country had ranked among lower-middle-income countries since 1950, by 2008 its GDP per capita (US$4,220 that year) qualified it as an upper-middle-income country according to the World Bank’s classification.

A major factor in Peru’s economic fortunes is the global price of metals and minerals, the production of which typically accounts for about 55 percent of the country’s total exports. Of course, this heavy reliance on a single sector cuts both ways – a decline in metal prices led to a downturn in economic growth starting in 2014, and continued after the end of the study period.

Taken together, Peru’s economic growth and the implementation of safety net programs led to decreasing poverty rates in Peru during the study period., The proportion of Peru’s population living below the national poverty line decreased from 59 percent in 2004 to 22 percent in 2015.

Income inequality also declined – the country’s Gini index decreased from 49 in 2000 to 43 in 2015. In 2015, Peru’s Gini index was lower than that of regional neighbors such as Bolivia (47), Brazil (51), Chile (48), and Colombia (51).

Increasing Investments in Health

As a result of considerable economic growth during the study period, health spending in Peru rose substantially, improving health care access and quality across the country. Total public and private health expenditure per capita increased from $326 in 1995 to $672 in 2015 (2018 PPP international $), according to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME).

In addition, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) found that expenditures for maternal health increased from US$828 per pregnant woman in 2006 to US$1,644 in 2012, and child health expenditure increased from US$119 in 2006 to US$319 in 2012.

Public funding accounted for 47 percent of child health expenditures in 2012 – up from 24 percent in 2006. This increase can be attributed to a focus on social assistance programs, and to strong civil society support for such efforts.

Maternal and Child Health Expenditures

Countdown to 2015, A Decade of Tracking Progress for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Survival: The 2015 Report. UNICEF and WHO, 2015. http://countdown2030.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Countdown_to_2015_final_report.pdf

Peru’s total spending on health as a percentage of GDP, however, remained almost unchanged during the study period – 7.0 percent in 2000 and 5.2 percent in 2015 – and remained below 7.1 percent, the average in Latin America and the Caribbean.,,

While total national health spending shifted little, the share of that spending accounted for by government expenditures rose from 52 percent in 2000 to 60 percent in 2015. In 2014, the share of health expenditure provided by the government was similar in Peru (58.7 percent) to the regional average (56.7 percent).

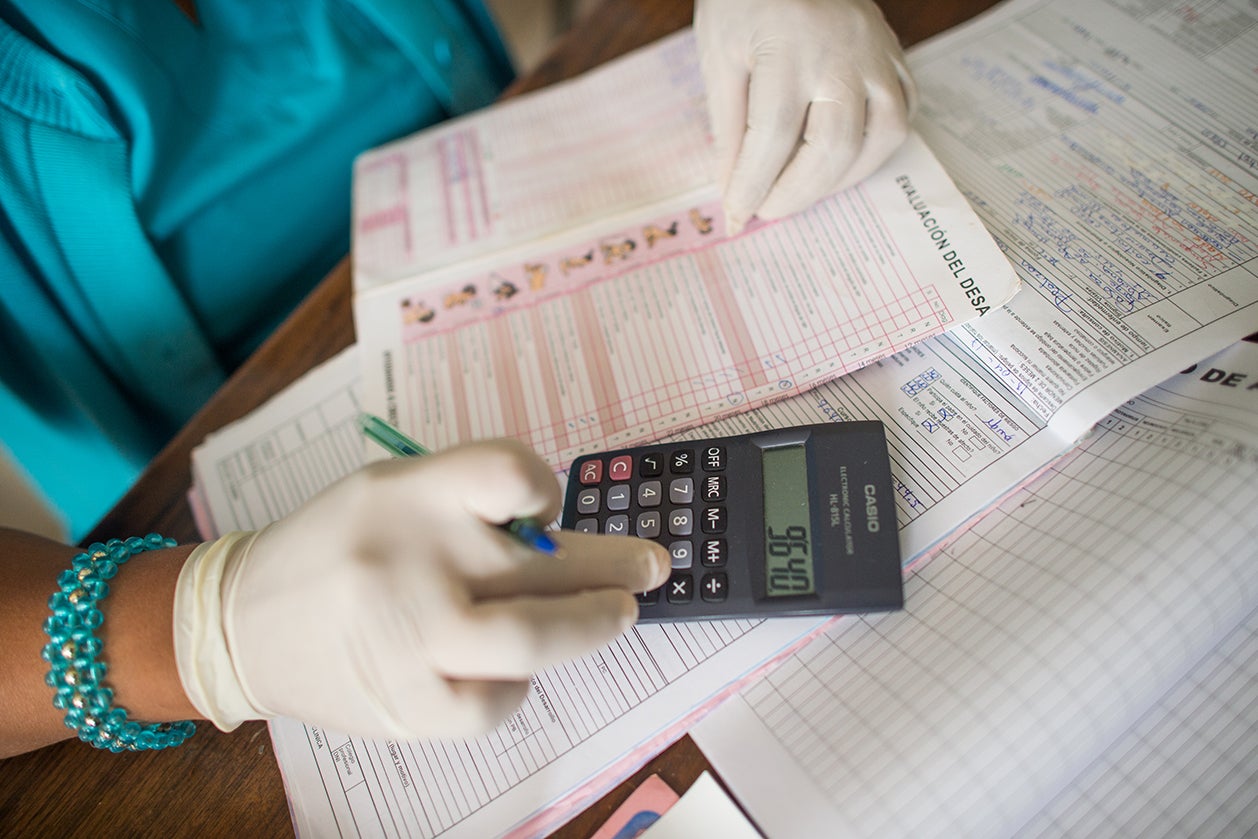

Crucially, these increases in public sector health spending were accompanied by a strengthening commitment to fiscal reform and accountability. By the end of the study period, for example, Peru had established high levels of budget transparency for maternal health programs compared to other countries in Latin America.

The financial reform that had perhaps the most impact in Peru was the implementation of the results-based budget program, a tool used by all ministries to allocate funding on the basis of measurable outcomes.

This practice began with the Budget Law of 2008, and was first implemented in 2009. It requires cross-sectoral collaboration between ministries, and ensures that any ministry-funded program be tied to specific, measurable results.

Before results-based budgeting, it was difficult to report on and evaluate health spending related to maternal and child health initiatives, and to evaluate the outcomes of existing funds and determine resource allocations.

One interviewee said of this period, “It is not that the resources were not allocated, but that they were not aligned with specific programs, and you wanted at that time to say how much the country is investing in reducing maternal and child mortality, and you looked at the budget structure, there was no way to tell.”

Beginning in 2009, programs needed to show that interventions were based on scientific evidence and resources were clearly aligned with the intended outcome of the program.

One key informant noted this was a more efficient way of spending government resources for programs aimed at reducing child mortality. “We believe a major factor that has contributed to the reduction of malnutrition and child mortality has been to implement this resource-alignment strategy to budget for effective interventions that lead to a clear outcome. The results-based budget aligns institutions and services, and establishes a series of elements that help you spend what needs to be spent, concentrating the resources on what we know is effective, and not wasting resources on other things.”

Since the results-based budget monitors outcomes based on empirical evidence, it had the additional benefit of tracking Peru’s progress toward achieving key maternal and child health indicators.

It also improved the sustainability of evidence-based practices implemented by the government. “The programs that are sustained over time are the policies that have been determined within the framework of these programs, so I think that is key, this permanent dialogue that has to take place between the sectors,” said one ministry official. “I think that's the big lesson we have, but also that we focus on evidence-based interventions. Not all countries do this – they don’t always make sure that the program is robust in order to be able to maintain itself over time, regardless of changes of government.”

Health Systems Strengthening

Among the ways that increasing health expenditures helped reduce mortality among children under the age of five (U5M) was the expansion and improvement of the health workforce. The World Health Report 2006 found that Peru was one of the few countries in Latin America facing a crisis-level scarcity of physicians, nurses, and other skilled health care personnel. This scarcity was reflected in low levels of provider density countrywide, and a concentration of skilled personnel in Lima and a handful of other major cities.

One major factor was the migration of professionals to other countries. From 1994 to 2008, more than 1,400 doctors and nurses left the country. At its lowest point, in 2002, provider density in Peru had fallen to 14.1 doctors and 8.2 nurses per 10,000 inhabitants.

To address this challenge, the MOH approved the National Policy Guidelines for the Development of Human Resources for Health in 2005. Some activities emerging from these guidelines included the training of more health care professionals, which led to staffing levels of 22.3 doctors and 25.9 nurses per 10,000 people by 2016. In addition, to retain health workers in rural areas, Peru created the SERUMS (Servicio Rural y Urbano Marginal en Salud) program in 1985. For graduates looking to work in the health sector or who received government scholarships, the program requires at least a year of working in a rural or underserved community.

Increases in doctors and nurses, 2002 to 2016

Scudin, J. La Infraestructura Hospitalaria Pública en el Peru. Congreso: Informe de investigacion 27/2016-2017. Lima, Peru: Congreso de la Republica; 2016. http://www2.congreso.gob.pe/sicr/cendocbib/con4_uibd.nsf/97d83d04226344ec0525809500726521/$file/infraestructura_hospitalaria.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2020.

The MOH also invested in health infrastructure during the study period. According to a key in-country informant (interview, March 2019) , the number of MOH-run health facilities increased from about 2,500 in the early 1990s to around 8,500 after the end of the study period. Additionally, access to reproductive health care services increased, such as through the creation of Maternal Waiting Homes and midwife education programs in rural regions and increased antenatal care services.

Expansions in Health Insurance

Peru has initiated a range of insurance programs to increase financial protection and access to health care, starting with the most vulnerable and then extending more broadly.

Shortly before the study period, in 1997, Peru launched the School Health Insurance program (Seguro Escolar) to provide free health care to children enrolled in public schools across the country.

The school-based insurance program, financed by the government, was implemented to encourage parents to enroll their children in schools. Although there was no systematic study to assess the net increase in coverage, many hospitals reported higher school attendance after the program was established.,

In 1998, the Maternal and Child Insurance (Seguro Materno Infantil) program was launched to provide health insurance to pregnant women and children under five. The program received funding from the Peruvian government, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the World Bank.

In 2001, the government decided to merge the two insurance programs to create Comprehensive Health Insurance (Seguro Integral de Salud). The Comprehensive Health Insurance program aimed to address continued gaps in health care access by extending coverage to all impoverished children under 18 – regardless of public school attendance.

Another vital expansion of health care coverage was the implementation of the Comprehensive Health Insurance (CHI) program. Established in 2002, CHI built upon an existing insurance plan for mothers and children, and aimed to reduce or remove out-of-pocket costs for public health facilities and allay financial barriers to accessing health care.

In particular, CHI contributed to improved rates of facility-based births in Peru, which rose from 24 percent in rural areas and 83 percent in urban areas in 2000 to 68 percent in rural areas and 96 percent in urban areas by 2012. For more information on efforts to increase facility-based childbirth rates, see the article.

Use of data for planning and allocation of resources

Peru's robust data surveys have helped with both informing policy and monitoring health outcomes. For context, Peru’s annual Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) (called the Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar [ENDES]) is one of the most robust national-level data collection tools in the world. It collects national data twice yearly and department data annually. Importantly, it allows researchers to disaggregate findings by the country’s three main geographic regions: the coast, the mountains, and the jungle areas.

Regarding informing policy, results from the ENDES sparked the conversation around poverty in Peru, ultimately leading to the 2001 establishment of the Roundtable for the Fight Against Poverty and the 2002 National Agreement, both of which signaled an emergence of a national consensus on the importance of ending extreme poverty in Peru.

In addition, the ENDES survey also has been critical for monitoring the effectiveness of policies. One key informant (interview, March 2019) said that

“The ENDES became a very important tool of quality control of processes... For example... if we allocate resources for the right programs, we have also been able to see what was going on with rural deliveries that had one of the most complicated areas of coverage."

The key informant continues that the ENDES data enables analysis of how resource allocation is improving coverage in different parts of the country, such as with facility-based delivery in rural parts of Peru. In this manner, the ENDES data enabled monitoring of health outcomes and connected this with policy decisions being made.

While Peru can continue to expand the types of data they collect (including data from civil registration, e.g. birth and death certificates, and other data on administration, services, and quality), the ENDES survey and data use more broadly has been an integral part of Peru's under-five mortality reduction.

Improvements in Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene

Previous research on child mortality reduction in Peru has identified improvements in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) as another important contextual factor in the country’s progress.

Households in Peru with access to improved water sources increased from 80 percent in 2000 to 88 percent in 2012. This improvement in WASH likely contributed to reduced incidence of childhood diarrhea, which has historically been a major cause of U5M.

However, inequities in WASH do remain in Peru – in 2012, 93 percent of households in urban communities had access to an improved water source but only 76 percent in rural areas. Partly as a reflection of this urban-rural divide, large regional differences also persisted, with access to improved water sources ranging from 94 percent in Lima to only 60 percent in Loreto.