Key Points

Despite its success in reducing U5M, Rwanda faces challenges to maintain and improve on progress.

Neonatal deaths: Costlier measures are needed to combat prematurity and low birth weight, as neonatal mortality becomes a growing proportion of overall under-five mortality rate.

Diagnosis and treatment for HIV-positive infants: Early infant diagnosis and access to antiretroviral therapy fall short for children under five.

Policy setbacks: Lack of human and physical resources to support the integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) program led to delays in implementation.

Neonatal mortality

As noted throughout the Rwanda story, some of the greatest challenges involve precisely those diseases and conditions that the nation has long identified as its most urgent U5M priorities.

For example, while Rwanda is a leader among sub-Saharan African nations in reducing acute malnutrition, it has yet to successfully address the chronic malnutrition that potentially compromises a range of public health objectives, including the health and survival of neonates and young children.

Neonatal-mortality prevention remains an area of relative underachievement. While neonatal deaths are declining, they account for a growing share of Rwanda’s overall U5M rate, and outcomes for the youngest infants - those under one month of age - have been a matter of particular concern. In addition, the nation will have to undertake costlier measures to address the problems of prematurity, low birth weight, and heart disease, all of which now account for higher proportions of neonatal mortality.

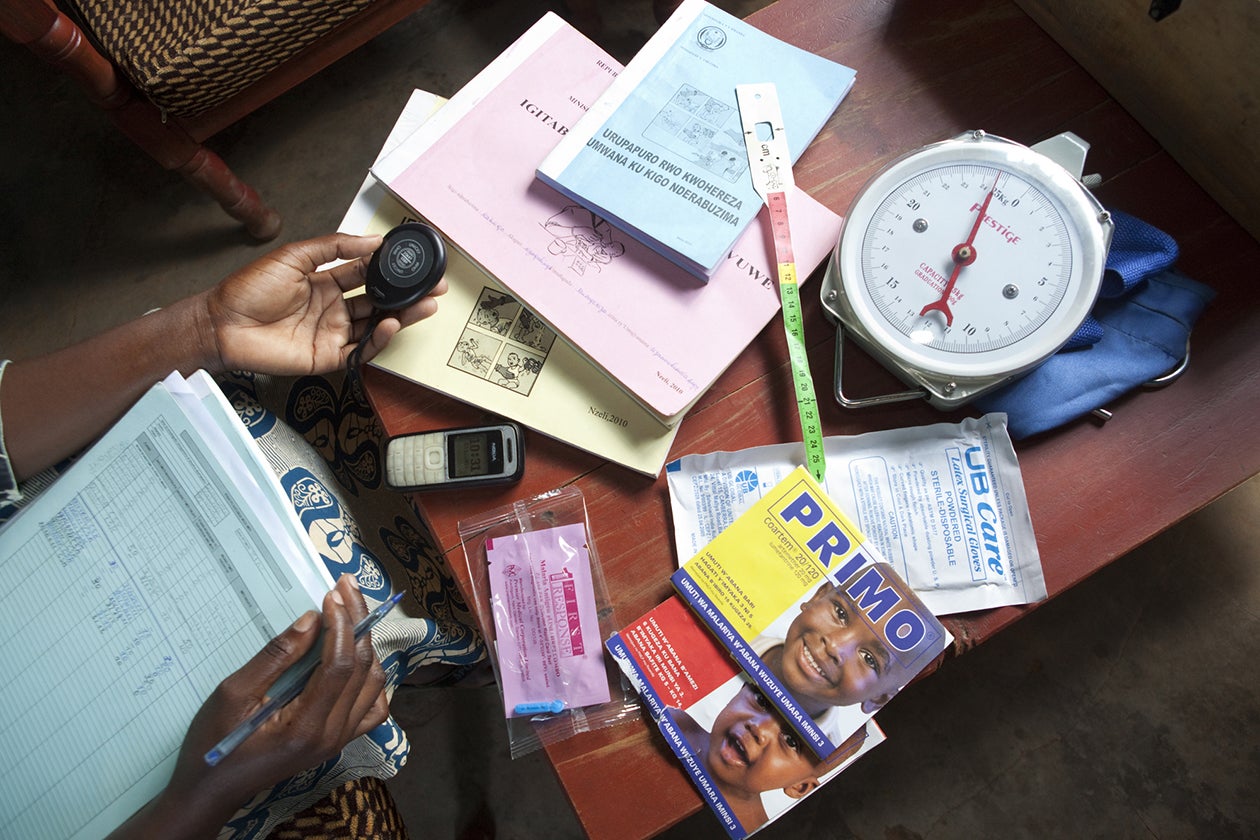

One of Rwanda’s most important means of confronting neonatal mortality and other forms of U5M has been the nation’s ambitious and extensive community health worker (CHW) program. However, the funding and retention of CHWs has proved to be difficult, and an inability to address these issues could compromise public health delivery and U5M interventions in rural villages nationwide.

Among the most effective of those interventions has been the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV. But another critical intervention against the disease - early infant diagnosis, or EID - has been less successful. Because more than half of HIV-positive infants will die by the age of two without treatment, this is an important gap in Rwanda’s U5M program. While 70 percent of all health facilities in Rwanda were offering EID services by 2009, only 28 percent of children born to HIV-positive mothers were receiving EID.

Furthermore, even with expanded access to antiretroviral therapy (ART), the treatment of HIV-positive children remains limited. In 2013, only 60 percent of HIV-positive children up to 14 years old were receiving ART, compared to 95 percent of HIV-positive adults.

Evolving external factors could also jeopardize Rwanda’s hard-earned gains against U5M.

Regional challenges

Since 2012, Rwanda’s malaria incidence and death totals have steadily risen. Contributors to this increase may include delays in ITN procurement and distribution, as well as growing resistance to the insecticides used in Indoor Residual Spraying. Significantly, similar increases in malaria rates have occurred across East Africa, indicating that broader forces may also be at play.

In addition, political instability in neighboring countries could expose Rwandans to new threats, such as the reappearance of measles in areas abutting Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

In 2010, Rwanda registered 121 documented cases of measles - all of them either occurring in districts bordering Burundi and the DRC, or directly traceable to index cases from one of those districts. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) - in coordination with the Ministry of Health (MOH) - now vaccinates all displaced persons at the Rwandan border for measles and polio, and conducts routine vaccination campaigns in refugee camps.

Implementation setbacks

One of Rwanda’s earliest U5M initiatives was the adoption in 2000 of the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) protocol, which had shown promise in other countries.

Developed by World Health Organization and UNICEF in 1996, IMCI is intended to help high-U5M nations improve the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of common childhood illnesses, with an emphasis on strengthening overall health systems.

Even though IMCI’s approach dovetailed nicely with the government’s health priorities, Rwanda encountered delays in implementing the program. The nation’s human and physical resources could not yet provide the level of support IMCI required.

At many facilities, the rotation schedules of thinly stretched staffs couldn’t accommodate the program’s intensive training regimen, much of which had to take place in district hospitals to ensure that there would be enough patients to conduct training in the first place.

Because of these and other factors, the MOH would not begin training health providers in the program until 2006. By 2007, only 23 percent of health centers had two or more IMCI-trained providers on staff. Yet despite this early disappointment, Rwanda’s development of effective systems to fight childhood illness was already well underway - and would accelerate in the years to come.