Key Points

The nation’s emphasis on community-level solutions – delivered by highly empowered community health workers – was a central factor.

Effective coordination with donors and partners also enabled successful uptake of interventions.

Senegal's improvements in data, research, and health surveillance capacity provided valuable evidence for decision-making.

Also crucial was Senegal’s willingness to invest in technology and infrastructure that facilitated the uptake and expansion of interventions to reduce child mortality.

Community Ownership, Equity and Accountability

Interviewees noted the importance of community ownership in interventions to reduce under-five mortality. “The first step is to involve people,” said one interviewee. “It’s the silver bullet triggering all the initiatives carried out in Senegal.”

This emphasis on community ownership manifested itself in various ways. Communities chose their own community health workers (CHWs), who played a crucial role in fostering community engagement in interventions to reduce under-five mortality, particularly Community-based Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (CB-IMCI) and antenatal care. Communities also provided the funds for building health huts (cases de santé) and obtaining basic medical supplies. Typically, communities apply to their district office under the Ministry of Health (MOH) to create a health hut. Once approved, communities must raise funds to construct, equip, and maintain health huts.

In some respects, Senegal’s emphasis on community-centered interventions is an outgrowth of the country’s long history of experimenting with various forms of decentralization, reaching back to the colonial period. In 1996, Senegal passed a local government law and in 1998, hospitals were designated autonomous “public health establishments,” giving them enhanced control of their own finances and overall management.

These reforms, along with the introduction of policies that encouraged public-private partnerships in the health sector, spurred an increase in the collaboration between the government and the private sector, with accompanying diffusion of healthcare responsibilities and improvements in delivery.

In 2006, the Health Development Committee of Senegal’s MOH began discussions to set up a local development health committee to lead the completion of the decentralization process. Senegal passed an Act of Decentralization in 2014 to accelerate this initiative.

Equity was a key factor in the success of community ownership and decentralization – they would likely not have advanced without community trust that the government’s health policies would result in greater equity. Indeed, Senegal factored equity considerations into its under-five mortality policies from an early stage, and implemented systems to meet this objective.

One example is the national government’s practice of choosing high-risk areas for the piloting and rollout of interventions, including the free delivery and cesarean policy (FDCP) pilot in the relatively poor regions of Kolda, Ziguinchor, Tambacounda, Matam, and Fatick, and the Programme de Renforcement de la Nutrition (PRN) pilot in Kolda, where acute malnutrition was especially prevalent. There are subtler examples as well, such as the disaggregation of rotavirus vaccination data by sex in order to track gender equity.

Another pro-equity measure that touched several under-five mortality policies was the waiver of user and access fees to ensure broader availability. This waiver was a core strategy of the FDCP; it also factored into the distribution of long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs).

Coordination with Donors and Other Partners

Most interviewees mentioned that strong collaboration among the Ministry of Health (MOH), implementing partners, donors, and other ministries was a major factor in Senegal’s ability to reduce under-five mortality.

Thanks in part to its relatively open, free, and stable political system, Senegal has enjoyed significant and sustained donor support. This has benefited the national campaign to reduce under-five mortality in numerous ways.

For example, the World Bank was instrumental in helping Senegal restructure the water sector and devise a multisectoral approach to nutrition. And the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has long assisted the government in developing a community health system. As one interviewee said, “It’s thanks to the conjunction of all [donors and partners] that IMCI experienced a very large scale.”

Donors and partners have acted as key collaborators, technical advisors, and implementers of interventions to reduce under-five mortality.

“All partners have been focusing on [under-five mortality] in Senegal particularly because of donors. All our programs are around improving maternal and child health,” said one interviewee from a partner organization. “Donor support in Senegal really is making it a focus, a priority in Senegal.”

This influence is mutual – the government’s obvious commitment to under-five mortality reduction has also shaped donor and partner priorities.

“I think it's on both sides,” said one interviewee. “The country is engaged at the national level through the political will, setting goals. The country has also aligned itself, engaged internationally.... The country was very interested and demanding, [so] partners joined.”

The government involved donors during the planning stage of various interventions, such as when it set up a working group – including representatives from USAID, the World Health Organization (WHO), and UNICEF – to guide the planning for implementation of facility-based IMCI (FB-IMCI). Similarly, preparations for the children’s intermittent preventive treatment of malaria program involved the development of policies, guidelines, protocols, and data collection tools with support from the Global Fund, USAID, and UNICEF.

The national government not only enlisted the ideas and expertise of donors and partners during the planning stages, it also relied on their guidance throughout the implementation of interventions. For example, Gavi co-funded the initial implementation of the government-led rotavirus vaccine and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) rollouts and financially supported the ongoing implementation of these programs, while WHO, UNICEF, and USAID provided technical support.

The main coordination forum for the different stakeholders working to reduce under-five mortality was the MOH’s Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health (RMNCH) cluster, which met monthly. Its members included partners involved in RMNCH work, such as UNICEF, WHO, and the World Bank. This cluster developed an annual work plan to focus advocacy efforts and address emerging priorities.

The RMNCH cluster also held an annual steering committee meeting with Senegalese non-health governmental stakeholders, including the Ministry of Economy, Finance, and Planning; the Ministry of Education; the Ministry of Labor; the Ministry of Youth; the Ministry of Women Affairs; and the Army. This ensured a comprehensive approach to addressing RMNCH issues, including under-five mortality reduction.

The RMNCH meetings reduced duplication of effort. As one interviewee said, “Because there are many stakeholders, we need to pool resources according to needs and priorities. If two stakeholders are in the same area, we are better pooling them instead of coming in the same area to do the same work without knowing each other’s programs.”

Another donor-coordination forum mentioned by interviewees was an MOH-led malaria committee that oversaw all activities under the National Malaria Control Program, including annual strategic planning and budgeting.

In addition to ministry officials, academics, and researchers, this multidisciplinary committee also included United Nations agencies and, eventually, the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), which had begun to provide support for malaria programming in Senegal.

Interviewees also identified the coordination of donors and implementing partners as an important factor in the successes of Senegal’s nutrition programs. Between 2001 and 2011, much of this coordination was overseen by the national government’s nutrition unit, Cellule de Lutte Contre la Malnutrition (CLM), which convened meetings on policy development and strategic planning.

While donor and partner support was an immensely positive factor in Senegal’s efforts to reduce under-five mortality, interviewees said it could also create disruptions when it was uncoordinated (as was the case in the oral rehydration program) or excessively time-limited (such as during the initial implementation of FB-IMCI).

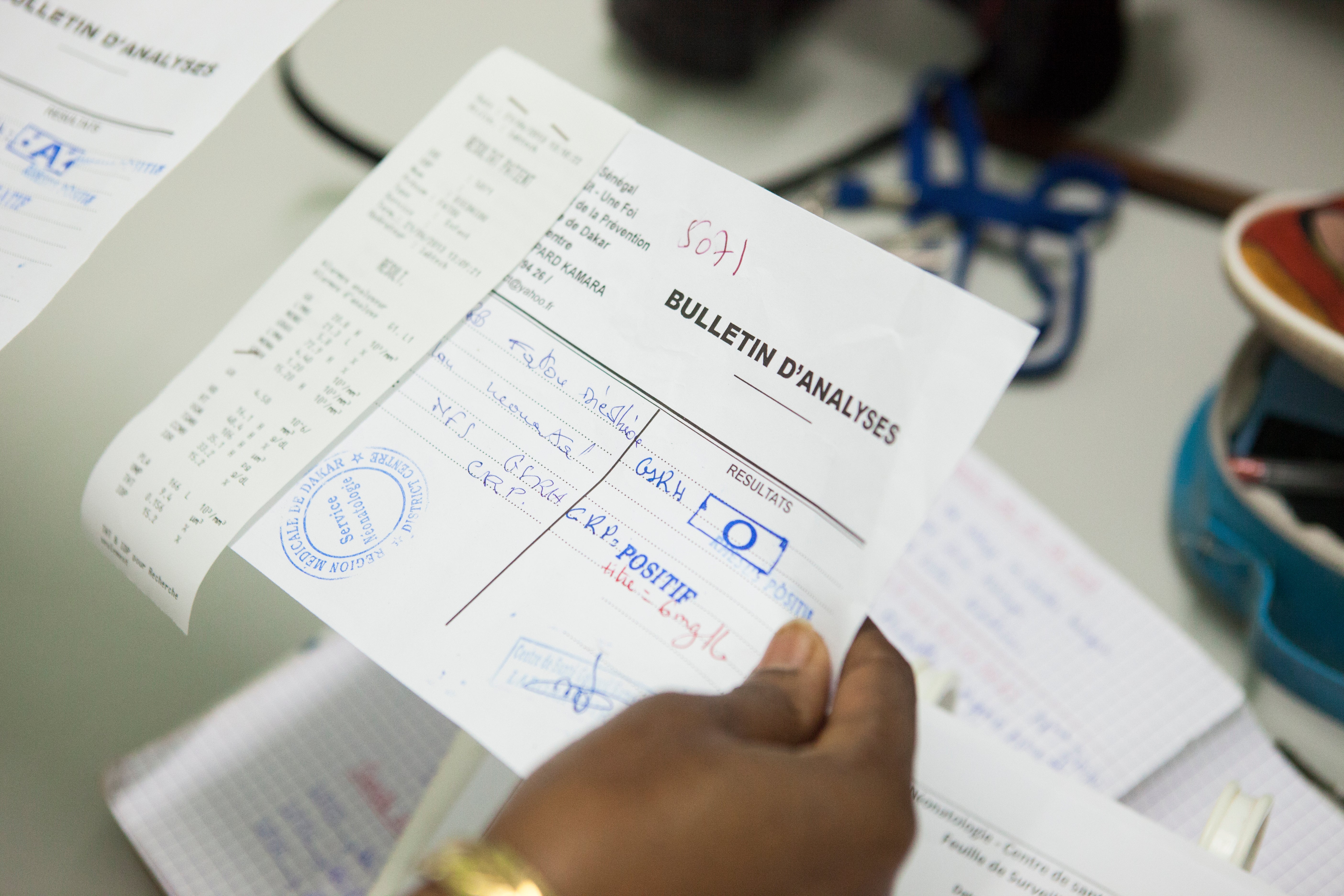

Improvements in Data, Research, and Health Surveillance Capacity

During the 2000–2016 study period, the national government pushed its own agencies and implementing partners to sharpen their use of data to address under-five mortality challenges and establish clearer lines of accountability.

“There have always been efforts to analyze data and to show where we have challenges and how we can improve it,” said one interviewee from an implementing-partner organization. “But I think [starting in] maybe 2000, there was a need to reach our target and improve how we made sure we were progressing. There was this idea of having quarterly meetings to analyze data and make it constant [and understand] what [and] why we didn't meet our targets.”

Interviewees also mentioned the importance of data in designing, planning, and piloting under-five mortality interventions that were appropriately customized for Senegal’s national and local circumstances, in advance of broader implementation.

One interviewee explained that pilot-level data helped all parties “see the costs of implementation; see where to scale up; evaluate all the needs that must be available first; quantify everything; and know which particular actors must be trained and supervised.”

There are several examples of such pilot-stage data assessments guiding broader implementations. Before the national switch to artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) for malaria, Senegal spent two years piloting an ACT program in Oussouye District, which was selected because it was a health and demographic surveillance site and could support the collection of surveillance data throughout the pilot testing.

A one-year pilot of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) for malaria was carried out in the same district, to further exploit the strong surveillance system already in place. Senegal identified the high cost of treating malaria without needing confirmatory tests and introduced RDTs three years earlier than the 2010 WHO recommendations – all thanks to high-quality local data.

Other important data-driven developments in the fight against malaria included the identification of chloroquine resistance in 2003, and the 2015 shift from deltamethrin to non-pyrethroids for indoor spraying based on local resistance findings.

A variety of systems propelled Senegal’s work to improve surveillance data. The country introduced its electronic health information system to synthesize facility-level data in 2005, and it proved to be a useful tool. A 2016 study assessing electronic maternal, newborn, and child health data across a group of low-income and middle-income countries found slightly above-average data availability in Senegal, with a score of 9 out of 15 points (the average score was 7.5).

The National Agency of Statistics and Demography in Senegal collects and presents data on different sectors, including health. The data are usually collected in partnership with the MOH and the Ministry of Economy, Finance, and Planning, and are used to monitor and evaluate the implementation of multiple national programs (including under-five mortality interventions) against predefined performance and coverage indicators.

Other useful data sources for under-five mortality reduction programs in Senegal include the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey and the National Nutrition Survey. Senegal has also conducted a Demographic Health Survey and a Service Provision Assessment each year since 2011, compared with most countries that typically conduct these surveys every five years.

Interviewees mentioned Senegal’s impressive use of data to inform decision-making at the subnational level as an essential component of under-five mortality reduction.

For example, all cadres of CHWs affiliated with a health hut collected routine data on their activities and submitted it to their supervising nurse every month for compilation. District officials review this data from all health posts and CHWs within a district in quarterly meetings to better understand and address operational challenges. District officials then took their data findings to regional meetings to share with MOH officials and implementing partners.

Senegal’s use of data enabled the government to balance the need for comprehensive local evidence with the value of moving forward with rapid adoption of potentially lifesaving measures.

Senegal repeatedly explored globally emerging interventions, but held off on implementation until local research and pilot testing had demonstrated their utility in the Senegalese context, for example, during the introduction of IMCI.

Yet Senegal also recognized the merit of rapid introduction and scale-up when necessary – when interventions did not require much context-specific adaptation, local data relevant to a given intervention already existed, or when similar interventions had already proven their worth. For example, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) was introduced on a broad scale without pilot testing. This was due to the strength of global evidence and the high levels of local acceptance of vaccines in general.

Even with the successful use of data, Senegal continues to experience challenges with data quality and effective application. According to interviewees, the national health information system had not yet reached complete reporting of health services provided, mainly as a result of gaps in data from private health facilities. Nonetheless, interviewees attested that Senegal continues to work actively toward improving data quality and use, especially at the district level.

Investments in Logistical and Infrastructural Systems

The fourth main success factor of Senegal’s under-five mortality interventions is the improvement of various infrastructural and logistical systems that support public health – especially supply chains and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) networks.

Senegal’s major vaccination drives – notably those for PCV and rotavirus vaccine – benefited from supply chain improvements, though Senegal’s performance on this front has been mixed. An evaluation of PCV introduction identified concerns about cold-chain storage capacity and temperature regulation. However, a 2015 evaluation found several positive developments in the country’s medical logistics, including an updated essential medicines list, a network of community workers capable of bolstering provisions at the local level, and procurement of necessary vehicles and information technology equipment.

At the same time, some lifesaving drugs and vital supplies (notably neonatal resuscitation equipment) remained insufficiently available during the research period.

While the country’s cold-storage chain had made necessary improvements, some interviewees said cold-chain capacity had only a limited effect on the quality of vaccine delivery, due to the use of vaccine vial monitors that helped delivery personnel identify whether a given stock was still usable.

The improvement of Senegal’s water and sanitation infrastructure represents an even more fundamental element of the country’s public health progress. Starting in the mid-1990s, the World Bank spearheaded a major effort to reform the water and sanitation sectors of Senegal. This was an important factor in under-five mortality reductions; studies had shown that a 1 percent increase in access to improved sanitation would avert two infant deaths per 1,000 live births.

Through the Water Sector Project and subsequent water and sanitation-based programming, Senegal increased access to key WASH services, at first primarily to urban areas. The country has more recently been searching for productive ways to serve rural areas as well.

In 2005, the World Bank and other donors assisted in the launch of the National Millennium Water and Sanitation Program, building on earlier efforts that privatized the urban water sector in the 1990s. This program supported national-level management of rural water systems and provided more leeway to private operators to manage rural water systems.

These and related measures brought significant gains. By 2013, 6.3 million of 7.5 million rural residents had access to safe water from boreholes, hand pumps, or modern wells. Nationally, the proportion of Senegalese with basic drinking water services increased from 62 percent in 2000 to 75 percent in 2015.

Sanitation lagged behind access to clean water. By 2015, the share of the population with available sanitation service was only 48 percent – a marked improvement since the 2000 level of 39 percent, but still considerably lower than the figures for water delivery.

While sanitation progress has occurred at the national level to various degrees, there has been a marked difference between cities and rural areas. Campaigns promoting “social connections” to sanitation were quite popular among city dwellers. In peri-urban areas, where sewer systems were not as affordable, the focus shifted to on-site sanitation and small-bore sewers, accompanied by subsidies and awareness-raising campaigns.

Between 2002 and 2008, the sanitation programs benefited 500,000 people, or 25 percent of the peri-urban population of Dakar. By 2011, this approach to expand access to sanitation was being replicated in five other cities with funding from the European Union.

Despite raising awareness and offering subsidy programs, sanitation in rural areas has been much slower to improve. This is due at least in part to the inflated cost and logistical difficulty of transporting construction materials from Dakar, which can make rural projects prohibitively expensive.

Even as access to water and sanitation services have improved significantly across the country, the incidence of related diseases has not decreased at the same pace. While the incidence of pneumonia declined significantly, the incidence of diarrhea showed minimal change, dropping from 22 percent to 15 percent between 2005 and 2016– though expanding the time period shows that incidence remained largely unchanged from 20 percent in 1992 to 18 percent in 2017.

It is unclear why such obviously improved sanitary conditions did not reduce the burden of diarrhea. One possible explanation is that while the incidence of diarrhea did not decrease significantly, the severity of cases did.

Senegal has continued to work toward progress on WASH, making 24 commitments related to water and sanitation at the World Bank’s 2014 Sanitation and Water for All High-Level Meeting in Washington, DC. The commitments ranged from increased financing to improved economic and gender equity in the provision of WASH services.

For additional information on water and sanitation improvements during the study period, see the accompanying report on .