KEY POINTS

The end of internal conflict allowed Peru to initiate two decades of economic development and political reform. From 2000 to 2016, several nationwide trends drove decreases in stunting prevalence among children:

Maternal, newborn, and child health:

Access increased in particular for mothers, who substantially increased the number of regular touch points with health workers during pregnancy and early motherhood.

Maternal nutritional status:

From 2000 to 2016, the average height of Peruvian mothers increased by nearly two centimeters.

Maternal education:

The median number of years of education among women increased dramatically from 2000 to 2016 (from 5.6 to 10.5).

Reduced fertility:

A drop in fertility and increase in interpregnancy interval allowed mothers to concentrate resources on fewer children and recover more fully between pregnancies.

Improved food security:

Large-scale migration from remote, high-altitude areas to lower-altitude urban centers improved access to less-expensive, more varied, and higher quality food.

Post-conflict improvements across sectors

With the end of the Shining Path guerilla war in the early 1990s and the decline of internal conflict thereafter, Peru began two decades of robust demographic, cultural, political, and economic changes.

Peru’s public budget nearly doubled in the first decade of the new millennium as government programs built bridges and roads connecting remote communities, bolstered mandatory school requirements, encouraged migration out of rural areas, expanded women’s access to safe and modern family planning, and supported agricultural development. While these programs were not part of the national stunting reduction strategy, they did serve to drive stunting reduction and were identified by our decomposition analysis as significant.

Our decomposition analysis, which regressed several potentially explanatory factors against height-for-age z-score (HAZ) for children under five from 2000 to 2016, found the following factors significantly related to stunting reduction:

We also examined the Peru Victora curves, which analyze how a child’s HAZ changes over time. Through this visualization, you can find a different interpretation of what improvements drove stunting reduction in Peru. You’ll find below a video explaining how to interpret the Victora curves and a data visualization of the Peru curves.

Victora Curves: Predicted HAZ score by child age

ICF, 2017. The DHS Program STATcompiler, (various) [data set]. Funded by USAID. Rockville, Maryland; 2017; INEI 2017. Encuesta Demografica y de Salud Familiar (ENDES), (various) [data set]. Government of Peru; 2017. Accessed 2017. Analysis done by SickKids

Maternal and newborn health care

In 2000, 68.5 percent of women had four or more antenatal care visits prior to delivery, with 62.5 percent of those deliveries accompanied by a skilled attendant. In 2016, these figures had increased to 96.0 and 92.4 percent, respectively.

These dramatic improvements in antenatal care and skilled birth attendance suggest that women in Peru significantly increased their contact with the health system over this period. Beyond the immediate benefits of antenatal care and skilled birth attendants, increased utilization of health services and interactions with health care providers likely improve women’s health practices in general. Healthier mothers give birth to healthier children who are less likely to be stunted.

Increased contact with health workers may also translate to reduced risk of stunting via better childcare. Mothers who see doctors and nurses frequently are more likely to receive good advice in nourishing their children and preventing or treating disease.

Our indicates that improved maternal and newborn health care is the biggest single determinant of stunting reduction, accounting for approximately 26 percent of the change in height-for-age z-score.

Maternal nutritional status

Maternal height and body mass index are two factors most predictive of stunting in children and correlate with reduced stunting in Peru over time.

From 2000 to 2016, the average height of Peruvian mothers increased by nearly two centimeters. While men’s average height also increased, it did so at a slower rate.

The larger increase in women’s height can be attributed to a general increase in wealth and improved nutrition across Peru as GDP rose, improved status of women, better access to health care for expecting mothers, and a significant reduction in teen pregnancy.

Teen mothers, their own growth spurt interrupted to feed fetal growth, tend to be smaller than older mothers. From 2000 to 2016, Peru’s adolescent fertility rate dropped by 26 percent, from 65 to 48 births per 10,000 15 to 19-year-olds.

Our indicates that improved maternal nutritional status accounted for approximately 24 percent of the change in height-for-age z-score.

Maternal education

The median number of years of education among women increased from 5.6 in 2000 to 10.5 in 2016. This increase significantly contributed to the stunting reduction as better educated mothers understand the importance of nutrition and growth monitoring, are better able to follow best practices, and are more likely to be empowered to access such services.

Our found that the increase in maternal education accounted for 16 percent of the change in height-for-age z-score.

Fertility

Improved access to modern birth control methods allowed women to have fewer children and to space those children further apart. The 1985 legalization of contraception gave couples greater freedom to determine how many children they have and the timing between each birth. Policies and programs launched thereafter, including the First and Second National Family Planning Program and the ReproSalud campaign, served to make modern contraception more available to women across Peru.

As women gained access to a wider range of safe and modern birth control options, they had fewer children and spaced those children further apart. From 2000 to 2016, the average number of births per woman ages 15-49 fell from 2.8 to 2.5 and the number of months between those births climbed from 36.9 to 55.6.

These trends reduced fertility, which accounted for nearly 14 percent of the change in the height-for-age z-score found in our decomposition analysis.

Further, smaller families generally improve the conditions of each family member by reducing competition for resources and overcrowding. From 2000 to 2016 the average number of people per household dropped from 4. to 3.7.

Smaller family size accounted for almost four percent of the change in height-for-age z-score found in our decomposition analysis.

Migration

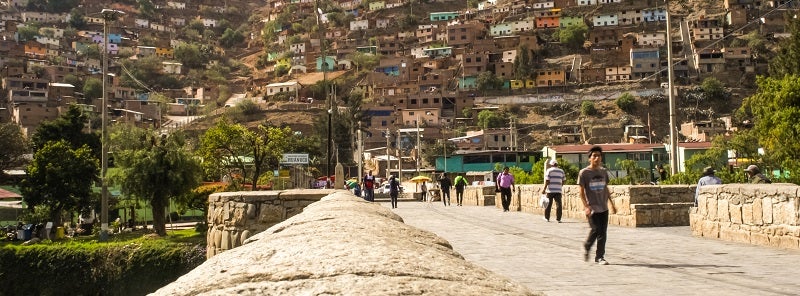

Population migration from high in Peru’s remote mountains to lower altitudes accelerated over the last two decades. From 2000 to 2016, the average household with a child under five surveyed by the DHS moved 20 percent closer to sea level, from 1390 meters to 1080 meters. This shift brought families closer to urban areas, roads, schools, markets, job opportunities, and health facilities. Importantly, migration closer to sea level also improved household food security by bringing families closer to more diverse and less expensive food sources. This significantly drove stunting reductions across all age groups. Our indicates that the change in altitude accounted for ten percent of the change in height-for-age z-score.

Economic growth and reduced poverty

From 2000 to 2016, Peru sustained a steady increase in GDP per capita, from $1,997 to $6,031 (current USD). Levels of poverty also sharply declined, with the percent of the population below national poverty line falling from 59 percent in 2004 to 21 percent in 2016. Inequality, as measured by the GINI index also decreased, but less significantly, from 50.8 in 2000 to 44.3 in 2015.

A reduction in poverty alone supports reductions in stunting, especially in a country like Peru where stunting disparities favoring the rich are pervasive. In Peru, the poorest wealth quintile consistently has the highest levels of stunting with the gap in prevalence rates between the richest and poorest illustrating the magnitude of the divide between rich and poor, ranging from 8 and 54 percent in 2000, and 3 and 30 percent in 2016. So as Peru grew richer, and standards of living improved for rich and poor alike, stunting rates naturally declined.

Our found that at the national level, income growth and reduction in poverty likely did impact stunting prevalence. Increased income allowed the Peruvian government to spend more on social welfare programs which had a direct impact on stunting.

National registration and identification

It can be difficult for a government to provide services to citizens that it does not know exist and cannot keep track of. Recognizing the need to ensure that the rural poor were integrated into government social programs, Peru built what is considered one of the strongest and most inclusive national identification programs in the world. The Sistema de Padron Nominado, a national registry of children under six, makes it possible for the government to accurately plan for supplies and services to reach the most remote and impoverished communities - essential for any results-based financing program. Birth registration ensured that every Peruvian family could gain access to state-funded or provided health and child care services.

To achieve high participation rates in the system, the government instituted a series of changes starting in 2001: it simplified the process for issuing birth certificates, eliminated fees in poor and remote areas, and opened registry offices in hospitals across the country to lower barriers to universal coverage. In 2005, identification was incorporated into the Juntos conditional cash transfer program, incentivizing rural women to obtain identification for themselves and their children.

Today, Peruvian birth certificates include a unique eight-digit number which becomes a person’s unique identifier for life. Identification numbers allow the government to track the delivery of services and ensure that children, no matter where they live or where they move, receive the necessary preventive care. The Padron Nominado registry is stored on an electronic platform and contains the following data for each household:

- Names and, surnames of child, father and mother

- ID numbers

- Address

- Affiliation to social programs

- Type of health insurance

Information is drawn through collective data from SIS, Juntos, and other sectors, including the Ministry of Education. The data is used to measure the coverage of health services and social programs at different levels by region, province, district and community; it enables effective institutional coordination to ensure that services reach the most isolated citizens.

Comprehensive health insurance for the poor

In 2002, a new comprehensive health insurance program, Seguro Integral de Salud (SIS) which covered all poor children under 18 years of age as well as pregnant women, removed a formidable barrier to the use of health services and provided a critical foundation for inculcating health-seeking behavior.

By 2015, 75 percent of urban Peruvians and 90 percent of rural Peruvians were insured. Coverage in the five poorest states of Peru ranged from 90 percent in Apurímac to 77 percent in Cajamarca in 2013. Without a free health insurance program, Peru could not have connected the poor with the crucial preventive health care that helped drive stunting reduction.

A network of rural clinics

A series of initiatives from the mid-1990s to 2010 developed a system of rural health clinics and equipped those clinics with the resources and staffing necessary to deliver the preventive care that drove stunting reductions across Peru.

Salud Básica doubled the number of health posts, health clinics, and health centers between 1995 and 2000.

To staff those clinics, Peru launched Servicio Rural y Urbano Marginal en Salud, (SERUMS), requiring new graduates seeking a career in the public health sector, or those who received government scholarships during their studies, to work for one year in an underserved community. In 2009, the government updated SERUMS to ensure larger numbers of health workers were placed in the poorest communities. As a result, the number of health professionals placed in the poorest communities increased by 70 percent from 2007 to 2013.

But to recruit the large numbers of health workers necessary to effectively serve rural areas, deliver preventive health care, and conduct the growth monitoring that formed the core of the country’s stunting reduction program, Peru implemented Programa Articulado Nutricional (PAN), a results-based financing program that significantly increased funding for health care in rural areas, allowing rural states to hire the staff necessary to meet their goals. As a result, the number of health workers in some of the poorest states of the country more than tripled.

Peru’s stunting reduction program would have missed the poorest communities, where stunting is highest, if the government had not invested in extending the health system to rural areas.

Improved reproductive health

Peru experienced a significant shift in fertility patterns over two short decades:

- From 1996 to 2016, the average number of children per woman age 15-49 declined from 3.5 to 2.5

- Over this same period, the median number of months between births climbed from 33.0 to 55.6 months

Both of these trends improve both mother's health and their ability to care for their children. Having fewer children, with more time in between pregnancies, allows women to devote more resources to each child and recover more fully between births. In our , improved fertility accounted for nearly 14 percent of the change in HAZ.

As fertility declined, so did the number of people in each household. From 1996 to 2016, the average number of people in a household dropped from 4.8 to 3.7. Smaller families meant more resources available to each member of the family and less overcrowding. This decrease in the competition for resources in the home accounted for almost four percent of the change in HAZ in Peru in our .

Significantly, access to modern family planning, as well as other programs, also helped reduce adolescent pregnancy. From 2000 to 2016, the adolescent fertility rate fell from 65 births per 10,000 women ages 15-19 to 48.

Adolescent mothers are not only often stunted themselves because pregnancy interrupts their growth, but they are also more likely to have underweight children, less likely to breastfeed, and less likely to ensure their children receive the necessary health care that can protect against stunting. The reduction in adolescent fertility, therefore, has significant benefits not only for those individual women, but also for their children and the country’s stunting reduction campaign.

Our decomposition analysis found that maternal nutritional status, which includes maternal height and maternal body mass index, was the second most important determinant of Peru’s stunting reduction.

Access to modern family planning likely contributed to Peru’s stunting reduction programs by improving reproductive health and reducing household sizes.

Peru’s family planning initiatives started in 1985, when the country guaranteed couples the freedom to determine how many children they have and how to best space their children by allowing voluntary contraceptive use. Between 1986 and 2016, prevalence on modern methods of contraception among women ages 15-49 increased from 23 to 54 percent, with 95-100 percent of women consistently reporting knowledge of modern methods of contraception.

This historic policy shift was followed by programs to ensure that women, no matter where they live or how much income they earn, have information about and access to modern family planning resources. As women gained access to a wider range of safe and modern birth control options, they had fewer children and spaced their children further apart; As a result, adolescent fertility and the average size of Peruvian households declined significantly. Each of these trends in and of themselves benefits women’s health, and, because maternal health is such a powerful determinant of stunting - benefits the health of their children. Combined, they likely created conditions which strongly supported stunting reduction efforts.