The following section covers the interventions that were deployed in Ghana between March 2020 and December 2021 to respond to COVID-19 and maintain essential health services. Interventions during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ghana fell into three main categories: national, governmental, and population-level measures; health system–level measures; and patient-level measures.

Exemplars in COVID-19 conceptual framework for assessing epidemic preparedness and response

Even before the first case of COVID-19 was reported in Ghana on March 12, 2020, health officials acted to keep the novel coronavirus from entering the country. For instance, travel for state officials was banned, and Ghanaians in Wuhan, China, were not allowed to return in the early months of the pandemic.

As soon as health workers detected those initial cases, authorities activated an emergency preparedness and response plan aimed at detecting, containing, and delaying the spread of COVID-19.,, This was a familiar process: Ghanaian officials had established similar plans for previous health emergencies, such as the Ebola virus disease outbreak of 2016.

Read More

The emergency preparedness and response plan provided a road map for officials to coordinate Ghana’s pandemic response. At the national level, it provided guidance on establishing a National Technical Coordinating Committee (NTCC) supervised by the director general of the Ghana Health Service,, whose members were representatives from public agencies, international development partners, and research institutions such as the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research and the School of Public Health at the University of Ghana, to oversee the response. The NTCC organized subcommittees to design pandemic response activities in seven key areas:

- Coordination of logistics and operations

- Case management and rapid response

- Surveillance at points of entry and cross-border surveillance

- Epidemiological surveillance and data collection, analysis, and reporting

- Risk communication and social mobilization

- Laboratories and logistics

- Infection prevention and waste management

The NTCC also established a national Emergency Operations Centre to implement the NTCC’s plans in four key thematic areas: surveillance, laboratories, case management, and risk communication.

Officials also activated public health emergency management committees and rapid response teams at regional and district levels.

In mid-March 2020, officials began to implement the policies the NTCC designed:

- At points of entry, staff adapted a health declaration form they had previously been using to detect Ebola virus disease in incoming travelers. They also used thermal scanners and thermometers to take the temperature of travelers and restricted entry from countries with more than 200 reported cases of COVID-19. Borders with Togo, Cote d’Ivoire, and Burkina Faso were closed. International flights were suspended.

- Authorities declared a three-week lockdown in the Accra and Kumasi metropolitan areas where COVID-19 was spreading rapidly.

- Schools were closed and social gatherings were banned.

To support Ghana’s COVID-19 response, a coalition of civil society and community organizations—including private-sector entities such as banks, companies and industries, pharmaceutical companies, and wealthy individuals—donated money and key goods such as personal protective equipment (PPE) and test kits. Researchers note that the Ministry of Health also established a COVID-19 strategic plan and budget, initially more than US$600 million. The plan included laboratory, surveillance, case management, infrastructure, risk communication, and social mobilization.

Read More

Ghanaian authorities implemented strategies to maintain the delivery of essential health services as soon as flagging performance across essential health service indicators made it clear they were necessary.

Interventions to limit the spread of COVID-19 and maintain essential health services during the early stages of the pandemic in Ghana fell into three main categories:

- National, governmental, and population-level measures

- Health system–level measures

- Patient-level measures

National, governmental, and population-level measures

Health system–level response measures

In general, key informants noted that although the COVID-19 pandemic placed great strain on Ghana’s health system in some ways, it strengthened it in others. Pandemic-related innovations and adaptations brought the country a new infectious disease center, additional sites for laboratory testing, a greater capacity for mobile health, and a better sense of the gaps and challenges that persisted within the health system.

Between March 2020 and December 2021, Ghana’s health system–level response measures fell into two main categories: direct responses to COVID-19 and interventions to maintain essential health services.

Supply- and demand-side barriers to maintaining essential health services in Ghana during the COVID-19 pandemic

In almost every country in the world, the COVID-19 pandemic and efforts to mitigate it caused supply- and demand-side barriers to the delivery of essential health services. In Ghana, fear and health worker burnout were notable obstacles to maintaining essential health services, especially in the early months of the pandemic.

Fear

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, frontline health workers and prospective patients alike reported they were afraid of contracting the virus at health facilities. (Hospitals were initially classified as high-risk areas.) As a result, both groups avoided those facilities, leading to a tremendous initial decline in health service utilization across the country—even in places that were least affected by the pandemic.

Health worker burnout

In the early months of the pandemic, Ghana’s health workforce worked impossibly long days, and those not classified as “frontline” workers did not benefit from government incentives such as extra pay and tax rebates. Lack of PPE and failure to adhere to COVID-19 protocols in many health facilities contributed to high absenteeism among health workers. Low levels of staffing led to long waits in health facilities, which contributed to patients’ unwillingness to seek care.

In the years before the COVID-19 pandemic, Ghana’s health system made some substantial improvements in health indicators. For instance, life expectancy at birth increased from 62 years in 2010 to 66 years in 2019. The under-five mortality rate per 1,000 live births dropped from 80 in 2008 to 46 in 2019, the neonatal mortality rate per 1,000 live births dropped from 30 in 2008 to 23 in 2019, and the maternal mortality ratio per 100,000 live births dropped from 634 in 1990 to 308 in 2017.

Unfortunately, initial disruptions to essential health services during the early stage of the pandemic interrupted some of these improvements. A trend analysis conducted by the University of Ghana as part of this investigation found declines in outpatient department and antenatal care services, elective surgeries, tuberculosis services, HIV services, Child Welfare Clinic, malaria, postnatal care, hypertension, and childhood vaccination services..

The trend analysis also found that these indicators rebounded briefly, then dropped again around September 2021 (the onset of the Delta variant). That month, the Partnership for Evidence-Based Response to COVID-19 surveyed 1,280 Ghanaians by telephone and found that only one in eight of the respondents reported missing or delaying hospital visits due to the fear of contracting COVID-19. However, about 60% had missed visits for reproductive, maternal, or child health services because of this fear.

Read more: Africa CDC – Finding the Balance: Public Health and Social Measures in Ghana

Read more: PERC – Responding to COVID-19 in African Member States: Ghana

Quantitative analyses, however, found no evidence of significant lasting disruptions in the provision of essential health services in Ghana, likely because of the interventions implemented to avert them.

The charts below illustrate a trend analysis by the University of Ghana of coverage for each of the selected services before and after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Greater Accra. The red line, a counterfactual, predicts what might have happened in the absence of the pandemic.

Impact of COVID-19 on select health services in Ghana

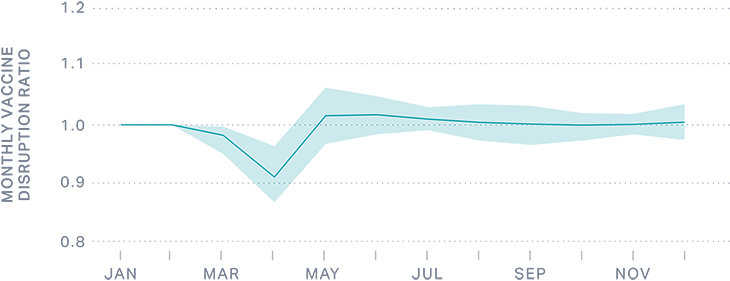

Disruption in DTP3 vaccine doses in Ghana, 2020

Based on an analysis from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation of administrative data, the figure above shows the ratio of the monthly number of doses of DTP3 vaccine (third dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine) given to children younger than one year old in 2020 as it compares with the same month in 2019. A value of 1 represents no change and values less than 1 indicate delivery disruption.

In March and April 2020, there was a substantial decline in the number of children who received received the third dose of DTP3 vaccine in Ghana. However, this ratio bounced back in May 2020 and Ghana was able to maintain DPT3 coverage throughout the rest of 2020.