Overview

The University of Ibadan, in partnership with the Centre for Global Child Health at the Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids), conducted research to identify key factors to reduce stunting in Nigeria. This research followed a convening of Nigerian governors in November 2019, organized with the Aliko Dangote Foundation and the Gates Foundation. During this meeting, participants expressed interest in collaborating with Exemplars in Global Health to undertake a subnational research study aimed at accelerating progress in stunting reduction in Nigeria. The resulting project generated actionable findings for a wide range of stakeholders in Nigeria and was shared at the National Nutrition Data and Results Conference in Abuja in October 2022.

Despite strong economic growth, declines in stunting prevalence in Nigeria have not matched expectations. From 1990 to 2018, Nigeria’s GDP per capita increased by 250%, from US$568 to US$2,028. However, during the same period, the national stunting rate fell by just over 5 percentage points, from 43.1% to 36.8%.

Figure 1: Nigeria Stunting prevalence and GDP per capita from 1990 - 2018

Many Nigerian states have faced challenges in translating their economic growth into tangible improvements in child growth and development. In these “opportunity” states, the prevalence of stunting actually increased slightly, from 42% in 2008 to 43% in 2018 ., Understanding the specific barriers faced by these states is critical, as they highlight clear areas for action to reduce malnutrition. The most significant challenges identified through our analysis are detailed in the Challenges section.

Progress in reducing stunting has varied substantially across the country. While national-level improvements have been limited, some states have achieved much faster reductions in stunting. These “Exemplar” states—defined as those with an average annual reduction in stunting prevalence greater than 0.8% between 2008 and 2018—saw stunting rates fall from 37% to 24%., The experiences of these states offer valuable insights into effective strategies for addressing child malnutrition.

Because of this variation, our research focused on the period between 2008 and 2018 to identify lessons from Exemplar states and explore how these approaches can be adapted to improve nutrition and advance other human development priorities across Nigeria.

Figure 2: Identification of Exemplar and Opportunity states in Nigeria

Why did we study Nigeria and its Exemplar states?

Stunting remains a major challenge for low- and middle-income countries. Although global stunting rates have declined, progress has been uneven, and many countries are not on track to meet global targets. Nevertheless, some countries have made remarkable reductions in stunting among children under five—beyond what would be expected based on economic growth alone.

To support government stakeholders in addressing malnutrition, the Exemplars team conducted research to identify key drivers of stunting reduction and variation between countries. Initially focused on national-level analyses, the research later expanded to subnational studies. This approach revealed that, despite limited progress at the national level, some states achieved substantial reductions in stunting. By studying these “bright spots,” we can uncover effective, context-specific strategies to improve nutrition.

As part of this effort, the Exemplars team examined stunting reduction in Nigeria, where progress has varied across states. Collaborative research by the University of Ibadan, SickKids, and Exemplars in Global Health focused on three central questions:

- Do differences between Exemplar and opportunity states reveal actionable lessons about best practices and policies that drove progress?

- For Exemplar states, what key drivers contributed to stunting reduction between 2008 and 2018?

- At the national level, why did Nigeria experience only moderate declines in stunting despite substantial economic growth?

A mixed methods approach was used to conduct this research. First, a systematic search of peer-reviewed and grey literature was reviewed. This was followed by quantitative and qualitative analyses, complemented by policy and program reviews and financing analyses . Quantitative analysis was conducted using the Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) from 2008 and 2018,3,4 and a Oaxaca-Blinder Decomposition was used to identify the drivers of stunting reduction. Risk factor analyses were conducted to identify variables or conditions that increase the likelihood of stunting in children under five years of age. Finally, qualitative analyses included expert and community interviews to understand stakeholder and community perspectives on drivers of stunting decline.

Completion of this research provided a large body of evidence, enabling a deeper understanding of the factors influencing stunting in Nigeria. By triangulating quantitative, qualitative, policy and program reviews, and financing analyses —and collaborating closely with in-country experts—the research team identified several key explanations described below.

What did Nigeria and Exemplar states do?

What did Nigeria and Exemplar states do?

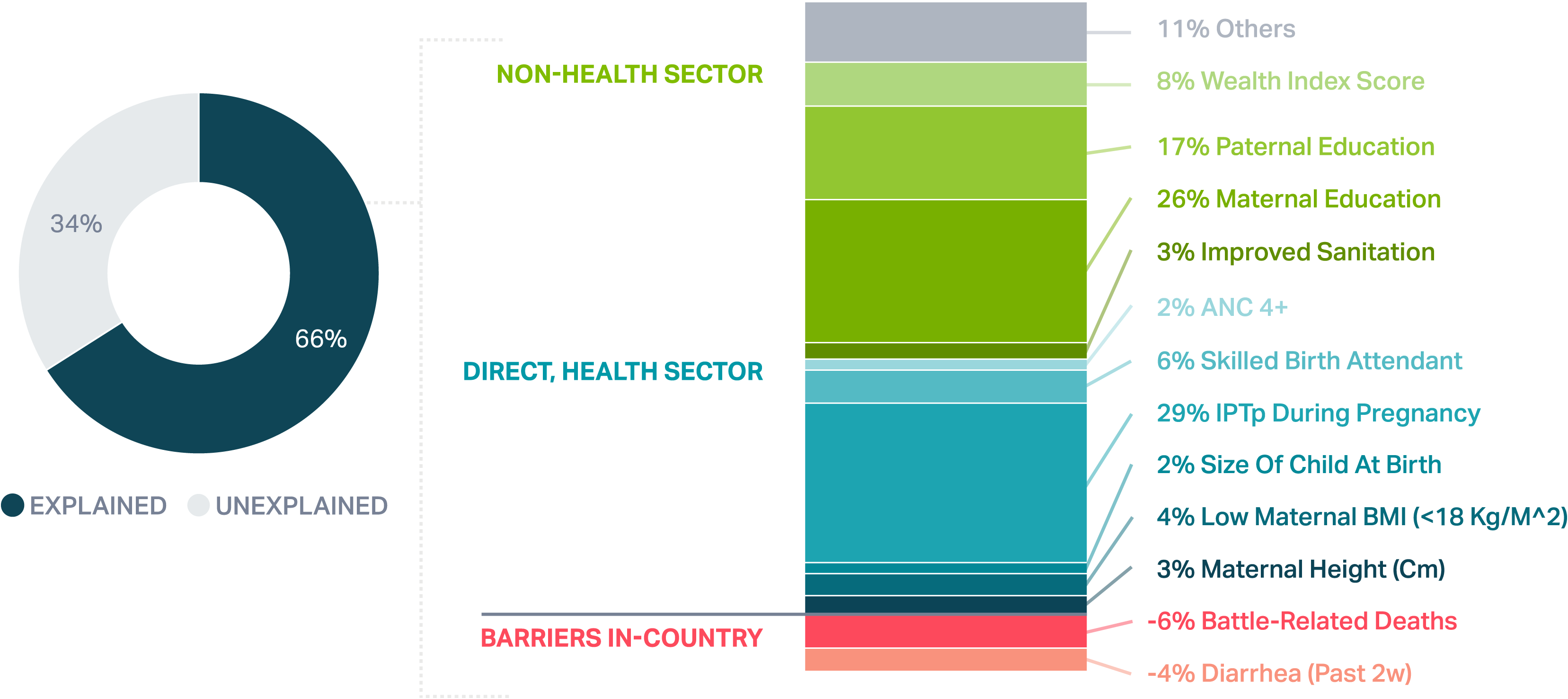

Figure 3: National Nigeria Decomposition Analysis

Before focusing on the Exemplar states, we first examined trends at the national level. The synthesized findings from Nigeria’s Exemplar states reveal a clear multisectoral approach, highlighting the importance of investments both within and beyond health systems. It is important to note that data limitations—particularly around nutrition-specific interventions (e.g., dietary intake)—may explain why a portion of the observed stunting reduction remains unexplained.

How might Nigeria and states implement moving forward?

Takeaways at the National level

The causes of maternal and child undernutrition are multifaceted and complex, and addressing them requires coordinated action across multiple systems, including health, education, sanitation, food, and social protection. The framework below provides a clear structure for summarizing the key takeaways and identifying the top priorities moving forward.