An increasingly digital world 'needs the infrastructure to match it'

CV Madhukar, CEO of Co-Develop, a global not-for-profit fund to help countries build digital public infrastructure (DPI) that is inclusive, safe, and equitable, reflects on how DPI can help a host of global issues

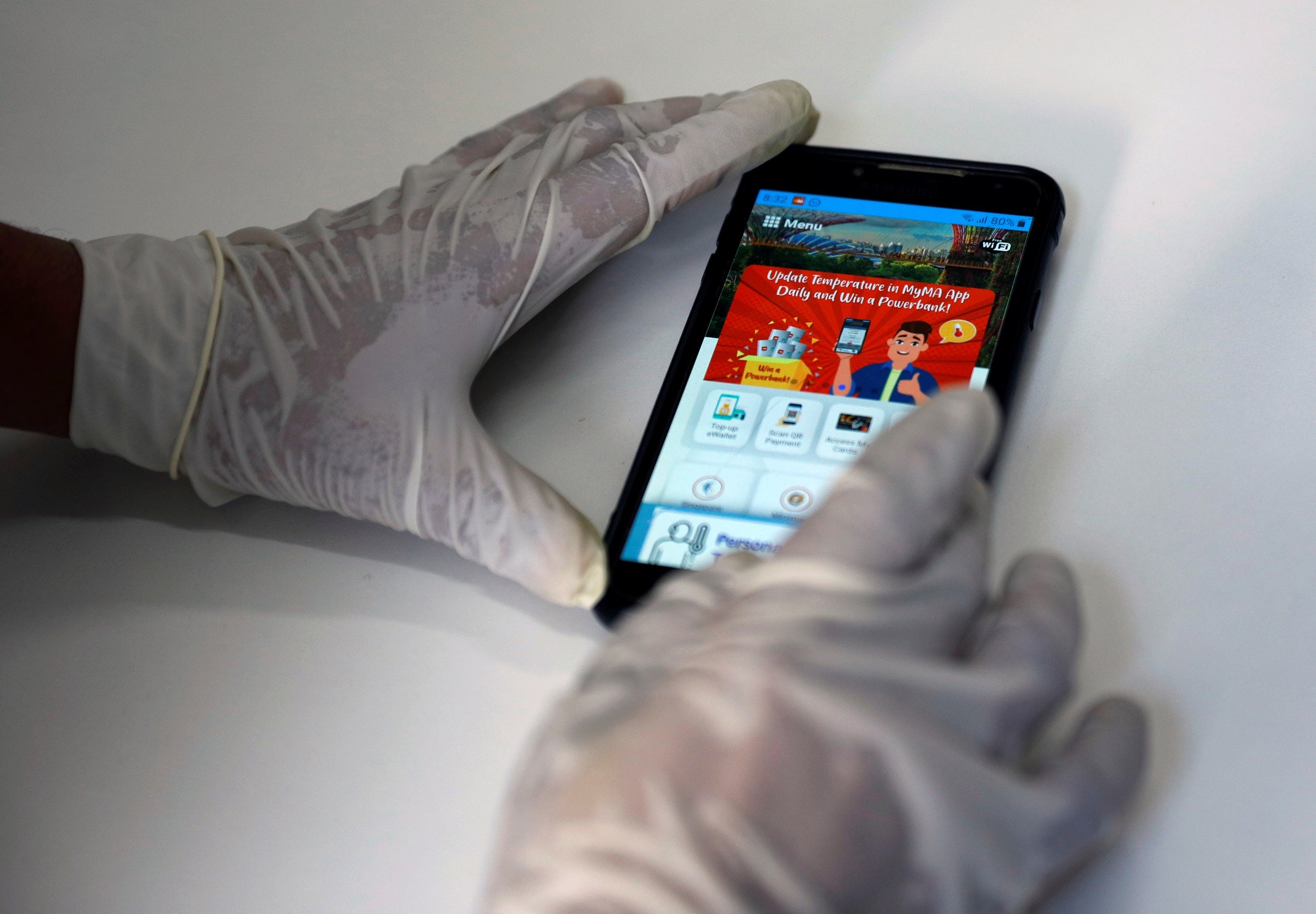

At the onset of the pandemic, we turned to technology – as we do in most modern-day crises – for quick and scalable solutions. With COVID-19 tearing its way through the globe, we found ourselves searching for ways to control the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and mitigate the effects it was having on our communities. Around the world, we relied on digital tools to help us stay connected with one another and remain updated on just about everything, from local hospital bed and ventilator availability to national PPE inventory stockouts to worldwide rates of community spread.

Every day, our highly linked world delivers faster and more effective digital communications, feeding into our expectation that there are infinite ways to access information, people, and things with merely a touch of a button. But that expectation belies a reality we too often take for granted: that the live dashboards, virus trackers, and health resources that seemingly sprout on our phones, computers, and tablets overnight could not come to be without a strong and preexisting infrastructure.

When we hear the word infrastructure, we tend to think of things like the roads that enable us to move from place to place, or the electricity grid, which is a national public utility. We may even think of the internet, as a seamless, global commodity used by virtually every sector in every country. But what we often fail to appreciate is the digital public infrastructure (DPI) – the robust yet invisible scaffolding on which most of the internet’s applications are built.

In the recent past, credit card payments were made with a swipe at a point-of-sale machine. Today, making a payment does not require us to have a card with us. It does not even require us to be physically present with a card in hand. But such digital payments are rendered impossible without an interoperable payments infrastructure that allows banks and intermediaries to enable real-time payments via an app. And when such infrastructure is provided by a "public" entity, it's called DPI. DPI puts the locus of decision-making in a wider community, and the data the infrastructure layer collects can be leveraged to stimulate local innovation. Unlike private infrastructure created by providers who hoard the data to improve their own capabilities and market share, public infrastructure can drive innovation and bring costs down for the user. Ultimately, DPI is that interoperable, seamless, mostly invisible digital plumbing and public good that helps us exchange information in an amalgamated and integrated manner.

Take companies like Uber and Amazon, for example, and their use of maps. Maps are common digital infrastructure they need across their respective platforms. But the maps they use were not built for Uber or Amazon. They were built originally with public and research funding because they were seen as important for countless other reasons. And, as a result, these two companies – and millions more – rely on that digital infrastructure to drop off a passenger or deliver a pair of shoes.

Robust DPI, like maps, GPS, digital payments, internet, etc. help drive innovation. Imagine if every app developer had to build this entire stack to provide services to citizens. When such critical infrastructure is shared it enables governments and entrepreneurs to build on top, rather than creating redundancies.

This thinking on how to build and leverage infrastructure is critical when the solution to a challenge does not have the benefit of time. During COVID, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in India developed an app for tracking vaccinations called Co-WIN that was used on top of existing digital identity infrastructure. The app was built and scaled to cover a billion people in a few short weeks.

More broadly, in the global health space, there are several notable apps that have been built out over the past decade or more to track malaria, tuberculosis, maternal and child health, among other diseases and conditions. But without unpacking what constitutes sector infrastructure, each of these apps repeats the collection of data that can be relevant and important for all these apps and more. Thoughtfully built DPI for the health sector can help accelerate attainment of health outcomes around the world. Because building good DPI means building a data architecture that is both private, because it is safe, and empowered, because it grants people access. In the case of health, it greatly benefits especially those who don’t have immediate opportunities to get care.

This is where Co-Develop, the organization I lead, hopes to play a role. Mid-pandemic, a convening called “Co-Develop: Digital Public Infrastructure for an Equitable Recovery” made the case for the improvement of horizontal infrastructure – things like IDs, digital payments, and data exchanges – to support sector infrastructure in areas such as health, education, and climate. At the event, The Rockefeller Foundation, the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Digital Public Goods Alliance, Nilekani Philanthropies, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Omidyar Network all pointed out the already growing need to make DPI the foundation on which to build a global economic recovery.

But for all of this to work, we need to see more stakeholders in governments, foundations, development agencies, civil society, and academia embrace the idea of the critical nature of digital infrastructure in attaining the Sustainable Development Goals. We will collectively need to make the case and make the necessary investments in developing the technology that can develop such infrastructure. At Co-Develop, we will need to support organizations that work closely with governments to think about this architecture, help them build legal and policy safeguards, and focus on individual and societal rights and safeguards. We will need to make a case for inclusion and how we can combine the physical plus digital – or phygital – so we do not exclude people. Building safe and effective DPI means working to close existing divides and ensuring population-scale inclusion.

The good news is that there is a confluence of at least four factors that offer an excellent window of opportunity for all of us to act. First, a number of countries have reached out to multilateral institutions to seek help in building DPI. Second, over the past decade or so about US$200 million of grant funding has gone into building open source code bases to solve the world's most pressing challenges. Third, we have population-scale proof points that these code bases can solve real development challenges. And, fourth, we have multilateral and bilateral agencies committed to providing funding to implement digital public infrastructure at population scale. These strong tailwinds will help us narrow the distance between the existing need and our ability to deliver.

In a world that is going to be increasingly digital as we progress in the 21st century, we need infrastructure to match it. Whether it’s for identifying and authenticating people digitally, or making transactions possible in the digital economy, performing a health diagnosis, or receiving education or employment online, we must build robust and sustainable DPI if we are to optimize the tools that exist to make all our lives better and healthier. The Open Forum Europe in a recent report exhorted the ecosystem to “reuse and co-develop where possible, redevelop only when needed.” This mantra might serve us all well, as we look ahead at the next decade and beyond.