Lancet Commission calls for investments in adolescent health and wellbeing

Report notes critical funding and policy gaps for the world's almost 2 billion young people, highlighting their unprecedented potential and calling for multisectoral collaboration and inclusive solutions

The second Lancet Commission on Adolescent Health and Wellbeing has called on health leaders to recognize and prioritize the needs of adolescents and partner with them to achieve a more just, healthier, and productive future.

Given the scale of this cohort – there are nearly 2 billion people between the ages of 10 and 24 – and their importance as the next generation of global leaders, the commission writes, that "investments made to ensure the health and wellbeing of this generation of adolescents [are] one of the best strategies to secure the future of humanity and the planet.”

“Given their size and influence, we ignore this group at our peril,” said the commission's co-chair, Dr. Sarah Baird, who serves as professor in the Department of Global Health at George Washington University.

Today’s adolescents represent a powerful and unparalleled resource for ensuring a better future for us all. “Investments in the current generation of 10-24-year-olds will reap a triple dividend, with benefits for young people today, the adults they will become, and the next generation of children they will parent,” says the report. “Adolescence is a key developmental phase when dramatic biological growth and psychological maturation have the potential, if nurtured and supported, to unlock the capabilities of young people to be the next innovators, educators, advocates, and leaders…”

Such investments are particularly critical for Africa and Asia, the commission notes, where more than 80% of the world’s adolescents currently live and for urban areas, where, by 2050, more than 70% of people under the age of 18 will live. “For Africa, where close to 60% of the population is under 25, this is a matter of survival,” said Dr. Alex Ezeh, co-chair of the commission and professor at Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health.

Nevertheless, adolescent health and wellbeing has not yet received the attention it deserves, say the authors of the report, which builds on its 2016 predecessor, Our future: a Lancet Commission on adolescent health and wellbeing.

The challenge is two-fold. First, there are still leaders and decision makers who do not recognize that adolescents have unique needs that are different from older or younger populations. Second, there often isn’t sufficient data or research to help guide health leaders on best practices for adolescents.

“Take the example of pregnancy,” said Dr. Baird. “What a teenager who is having their first child needs in terms of policies and support in programming is often quite different than what a 28-year-old choosing to have a child needs. But a lot of times, health systems or policy makers treat both individuals the same.” She added: “We want health leaders to be asking the question: What are the things that you should be considering when you're developing an adolescent-friendly policy or program? What does that look like?”

The commission aims to bring more attention to these questions and make them a regular part of health discussions. Critically, it hopes to promote more research and better data broken down by age and other factors, as well as generate more involvement from young people themselves around questions of their unique needs.

The report notes remarkable global progress in a few key areas of adolescent health and wellbeing, especially girls’ education. School-based health programs, age of marriage laws, and conditional cash transfer programs (such as Progresa in Mexico and Juntos in Peru) have helped girls stay in school. And improved education for girls has created the conditions necessary to support reductions in communicable diseases and improvements to maternal and child health and nutrition.

“When we think about broad drivers of improved health outcomes – especially for maternal health – all arrows point to the importance of educating girls,” said Augustina Mensa-Kwao, who served as a youth commissioner for the report and is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of Mental Health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “We’ve seen this outside of the commission’s work, in our Exemplars in Global Health research. Girls’ education shows up across every topic as a driver of progress.”

The progress in adolescent health, including in reducing communicable, maternal, and nutritional diseases, though promising and significant, has been uneven and lagged behind the more robust progress we’ve seen in health and development for young children. Further, what progress has been made in young children’s health, the commission writes, risks being eroded by challenges that are driving an increased burden of morbidity and mortality among adolescents.

The authors note that this commission comes at a time when adolescents face unprecedented obstacles, including climate change and environmental degradation, conflict and displacement, rapidly escalating rates of non-communicable diseases, and mental health disorders, the aftermath of COVID-19, and rising commercial interests and influences, including social media and online spaces. Today’s adolescents are the first cohort of humans who will live their entire lives under the shadow of climate change. They are twice as likely as adolescents 30 years ago to be exposed to conflict. And they have experienced an unprecedented rise in overweight and obesity rates.

“This is all worrying, especially in this current political and economic climate where we’re seeing foreign development assistance on the decline,” said Dr. Caroline Kabiru, lead of the Sexual, Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health Unit at the African Population and Health Research Center and a commission member.

National and global leadership has not yet risen to this challenge. There remains, the authors write, a "lack of global leadership and political will, a dearth of data by which to set goals and monitor progress, insufficient evidence for the design of effective, context-specific interventions, a shortage of appropriately trained, equipped, and supported workers, researchers and advocates, inadequate financial resources and poor coordination.”

Funding for adolescent health and wellbeing has thus far not matched the magnitude of these headwinds nor the urgency of the challenge. In fact, specific funding for adolescent health in low- and middle-income countries accounted for only 2.4% of total development assistance for health in 2016-2021, despite adolescents accounting for about a quarter of the world's population.

Such disproportionate funding indicates that leaders do not yet recognize the smart investment adolescents represent, the commission posits. Studies have estimated that for every US dollar spent on adolescent health, the return on investment ranges between US$5.40 and US$9.60. And the return is even higher when it comes to investments focused specifically on adolescent girls. “This is on par with the returns on investment typical for health programs for children,” said Dr. Ezeh. “And it is above the returns typical for investments in health programs for adults.”

The commission notes many reasons for hope. “Today’s adolescents live in a world of immense resources and opportunities, a world with unprecedented connectedness that is fostered by the rapid expansion of digital technologies, even in the hardest-to-reach places. Growing participation in secondary and tertiary education is increasingly equipping adolescents of all genders with new economic opportunities and providing pathways out of poverty…”

Indeed, even marginalized adolescents in remote communities are increasingly touched by digital innovation.

To build momentum and broaden progress, the commission emphasizes the need not only for more funding, but also better indicators and improved data systems at the subnational, national, and global levels, and enabling laws and policies that can create protective and supportive environments for adolescents. Effective policies and programming, across mental health, nutrition, sexual and reproductive health, also require multisectoral action – especially collaboration and coordination between health and education ministries.

Adolescents should be meaningfully engaged in the development of the policies and programming aimed at their cohort.

The commission modeled this approach by including adolescents throughout its research and development. Initiated in 2021, the commission brought together a diverse group of 44 commissioners who span disciplines, geographies, and generations and another 122 adolescents to participate in youth solution labs. Youth commissioners served as co-leads on each of the commission’s workstreams and youth reviewers provided feedback to drafts of the report.

“It was very much an equal partnership,” said youth commissioner Mensa-Kwao. “There were specific areas where we youth commissioners led the conversation.”

Youth commissioners prioritized developing an adolescent engagement best practices checklist – the first of its kind – that can be tailored to meet a wide variety of needs. “This tool assesses the level and nature of youth involvement, whether recognition through authorship or acknowledgment is warranted, and calls for reflection on the process – all while ensuring ethical and developmentally appropriate participation,” said Mensa-Kwao.

Broadly, the commission’s recommendations fall under five themes: addressing social norms related to mental health, sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), and gender; engaging sectors beyond health, such as education; reforming existing services (such as health, education, and SRHR); leveraging digital platforms and tech; and engaging adolescents as co-leaders and designers.

The commission’s report also presents several case studies to illustrate how targeted multisectoral actions can advance adolescent health and wellbeing. Those examples of coordination and cooperation include one case identified during research by Exemplars in Global Health research: Cameroon’s Multisector Program to Combat Maternal, Infant, and Adolescent Mortality. The program was established to promote collaboration between the public and private sectors, communities, traditional leaders, civil society, technical partners and financial partners.

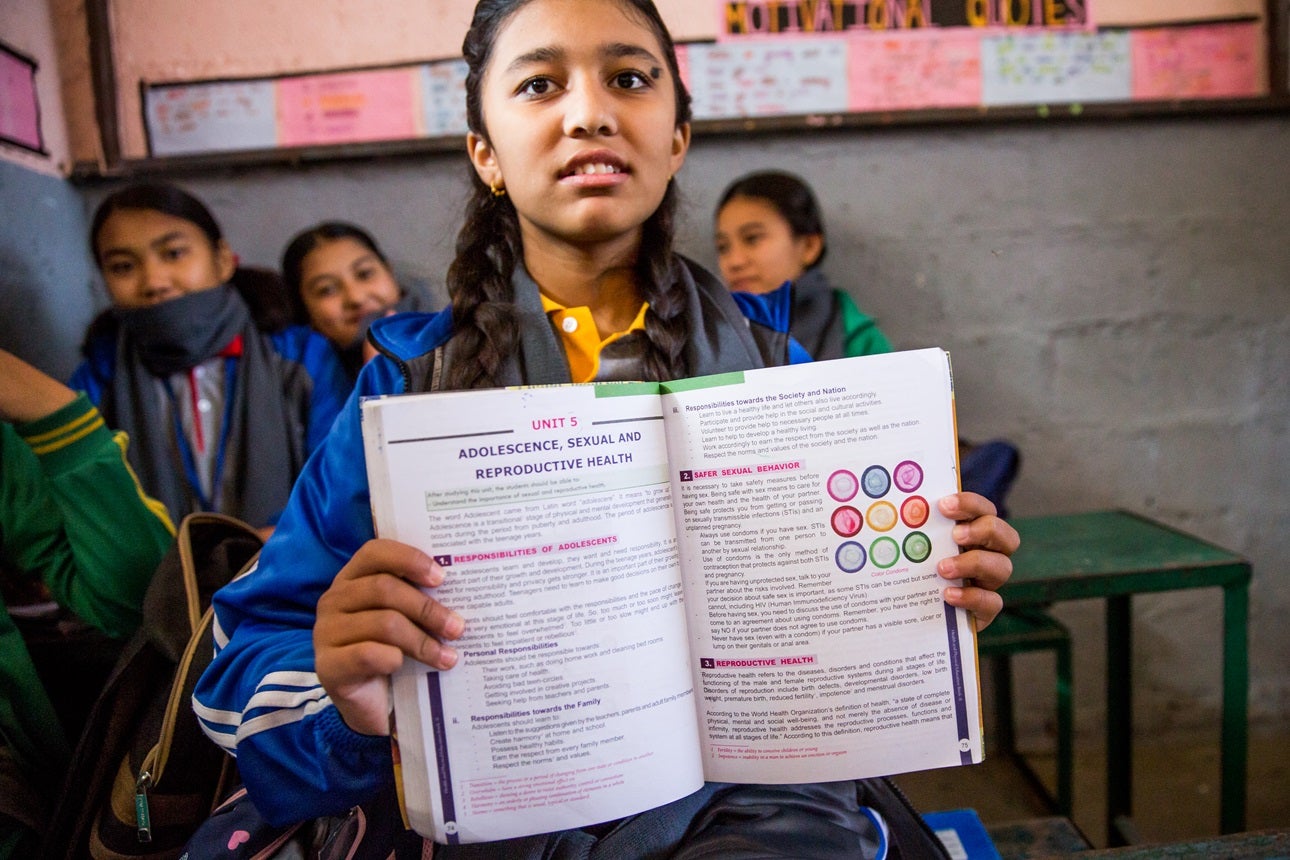

Another case study, this one from Nepal, illustrates how a country can enact a series of laws, policies, and programs to build momentum to support better health outcomes for girls. Nepal’s mutually reinforcing efforts, including the country’s National Reproductive Health Strategy, helped drive the adolescent fertility rate down from 110 births per 1,000 married females ages 15-19 to 71 per 1,000 and increase the median age of first marriage among women aged 25 to 49 from 16.8 years to 18.3 years over the past two decades. Nepal was selected as an Exemplar in ASRHR for the South/Southeast Asia region, and more details on how they achieved this progress will be published by the Exemplars partners later this year.

What Nepal, and several other cited countries, including Mozambique, Malawi, and Tanzania, demonstrate is that both preventing adolescent pregnancy and supporting pregnant adolescents is foundational. The WHO recently released guidelines on this important topic.

“Studies have shown that a quarter of young women and girls in sub-Saharan Africa will become pregnant in their adolescent years. If we are reluctant to support them, then there's no way we can achieve gender equality,” said Dr. Kabiru. “There's no way we can achieve many of the health and development goals and indicators that we hope to achieve, if we don’t intentionally and effectively support adolescent girls who are pregnant or parenting.”

With the goal of understanding country inequalities to better inform policy and programming, the report also includes research focused on subnational analysis in Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa. “We know that you really cannot address equity without subnational and subgroup analysis to identify where progress is being made and where it's not,” said Dr. Ezeh. “What we find is that there tends to be a concentration of disadvantage. For example, the same groups or geographies that have limited access to schooling also have limited access to health services, and other marginalizations or vulnerabilities. This concentration of risks compounds their disadvantages and manifests in poorer health outcomes.”

The subnational data in Kenya, for example, revealed remarkable declines in the burden of HIV and sexually transmitted diseases in female adolescents across most of the country. But at the same time increases in the burden for males across the entire country. Subnational data analysis in South Africa revealed increasing disease burden associated with maternal disorders across Limpopo and Northern Cape and especially North West Province.

“These discussions reinforced the power of data to bring visibility to particular health topics and groups of adolescents, which could help to reduce inequalities and improve health by better targeting interventions,” writes the commission.

One, often overlooked, issue the commission highlights is mental health. “Investment in adolescent mental health is disproportionately small relative to the magnitude of the problem,” writes the commission. Consider, for example, approximately 94 million adolescents live with anxiety and 57 million with depression – yet in lower-middle-income countries, only 6% of children and adolescents with any mental health disorder receive treatment.

The commission highlights levers schools and cities can use to promote adolescent mental health and psychosocial wellbeing. Making green spaces more accessible to urban adolescents and engaging adolescents in ensuring urban areas meet their needs, such as Brisbane Australia’s Plan your Brisbane program and UNICEF’s Child Friendly Cities Initiative, can improve adolescents’ mental health, strengthen their engagement, and foster connections.

Overall, to ensure this second commission has an impact, said Dr. Baird, “the report needs to be seen as the start of the conversation.” The commission’s work, noted Dr. Ezeh, “shows what can be done [to support adolescent health and wellbeing] and how it can be done. Now we need health leaders and leaders from other sectors to engage…Now is the time to act.”

Editor's Note: For more information about Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights, visit Exemplars in Global Health.

How can we help you?

believes that the quickest path to improving health outcomes to identify positive outliers in health and help leaders implement lessons in their own countries.

With our network of in-country and cross-country partners, we research countries that have made extraordinary progress in important health outcomes and share actionable lessons with public health decisionmakers.

Our research can support you to learn about a new issue, design a new policy, or implement a new program by providing context-specific recommendations rooted in Exemplar findings. Our decision-support offerings include courses, workshops, peer-to-peer collaboration support, tailored analyses, and sub-national research.

If you'd like to find out more about how we could help you, please click . Please consider so you never miss new insights from Exemplar countries. You can also follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn.