Key Points

Before the study period began, user fees paid for most health service delivery in Rwanda. This limited access to and utilization of key health services. Over the past two decades, however, Rwanda’s community-based health insurance (CBHI) scheme has become a global model.

Over the course of the study period, Rwanda also increased the number of health workers and health facilities, especially in rural areas. Along with other innovations aimed at increasing access to care, such as a nurse-led system of clinics for managing noncommunicable diseases, this has enabled close-to-community delivery of key primary health care (PHC) services. Rwanda’s Public Private Community Partnership (PPCP) model expands rural health care access through privately operated health posts, with Second Generation Health Posts further increasing service delivery and care utilization at a low cost.

Transforming health insurance

Figure 12: Rwanda’s timeline of health financing

Community-based health insurance

Since the 1960s, most of Rwanda’s health facilities charged user fees. In 1990, the country adopted the Bamako Initiative, which emphasized cost recovery and user financing as a way to make health systems more sustainable. Consequently, user fees for health services increased dramatically. However, this strategy limited access to care for the country’s poorest people. While supply- and demand-side incentives increased the quantity and improved the quality of health care services, health centers could only treat those who could afford the fees.

When the country set out to rebuild its health system after the 1994 genocide, officials briefly abolished user fees, only to reinstate them in 1998. Likely as a result, utilization rates decreased significantly.

To improve access to and increase the use of routine health services in particular, health officials soon began to experiment with demand-side mechanisms that would make those services more affordable to more people.

“After the war and genocide in 1994, people were very poor and none could afford to pay health services or premiums and so the population got free care for two years. However, free care was not sustainable. So, we introduced fees for service which led to an initial drop in consultation by nearly 70%. We all knew that this was also not right. This is how the idea to introduce CBHI was introduced.”

—Key informant interviewee

Self-reliance and mutual aid

In 1998 and 1999, the Ministry of Health (MoH), development partners, and donors began to experiment with expanding traditional community mutual aid initiatives, such as solidarity funds for neighbors experiencing health emergencies, into a more formal health insurance system in the Byumba, Kabgayi, and Kabutare districts. These pilots became Rwanda’s community-based health insurance (CBHI), also known as mutuelles de santé. With the aid of NGOs and other development partners, the program quickly expanded. In 2001, there were 60 CBHI schemes nationwide, and by 2004, there were 214. Utilization rates for key PHC services began to climb again. By 2008, and enabled by funding subsidies from the Global Fund to Fight HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the law required every Rwandan to have some form of health insurance.,

At first, CBHI annual? premiums were the same—RWF 1,000, or US$2, per family member—regardless of household income. In 2006, the MoH introduced standardized CBHI plans and free premiums for the poor. By 2012, the MoH had introduced a new premium structure based on household income and ability to pay. Wealthier families paid more, which helped subsidize the system as a whole.

Rwanda’s officials have consistently opposed the complete removal of user fees or universal subsidies for CBHI contributions. Researchers argue that this opposition is partly pragmatic—the health system does not have the resources to cover free or universal health care—and partly ideological. Pre-payment schemes like the CBHI, one official explained early on, support Rwandan values such as “solidarity, ownership, and self-reliance.” Although CBHI in Rwanda continues to depend on donor funding (19% of CBHI funding in 2020 came from earmarked taxes and donor funds as seen in Figure 13), the pre-payment and co-payment structures it introduced can enable self-sufficiency in the future.

Community participation

As their name suggests, Rwanda’s CBHI schemes are “community-based,” designed to foster grassroots participation. Tey are part of the broader “decentralization” project that emanates from the national government downward. The MoH defines the basic benefit package CBHI schemes offer, for instance, and encourages local governments to push for high levels of enrollment in their mutuelles by including this metric in imihigo performance contracts. ,

Funding

Figure 13: CBHI Funding by sources, 2020

Rwanda’s CBHI scheme relies on multiple funding sources. In 2020, user premiums accounted for half of CBHI revenues; the other half came from government budget allocation, cross-subsidy from other insurance schemes, earmarked taxes and donor funds, and other sources (Figure 13). Since management of CBHI was transferred from the MoH to the Rwandan Social Security Board in 2015, new funding sources include budget allocations from the government, salary contributions by individual workers, and earmarked taxes across multiple sources including:

- 50% of registration fees for pharmaceutical products and medical devices

- 5% annual contributions from other health insurers

- 3% turnover tax on telecommunications companies

- Fixed contributions (per liter sold) from fuel companies

- Fees attached to medical research, gaming companies, road traffic fines, penalties for trading substandard products, parking fees in Kigali, tourism revenues, vehicle transfers, and land rates,,,

Users pay a flat fee of RWF 200 (US$0.29) per health center visit, and copayments for services are capped at 10%.

Figure 14: Health insurance coverage rates, by wealth and rural/urban split

In addition to CBHI/mutuelles de santé, there are three other main sources of health insurance for Rwandans: Rwandaise d’Assurance Maladie for civil servants, Military Medical Insurance for service members, and private providers.

Rwanda health insurance coverage increased between 2005 and 2020, from 43.3% of individuals with health insurance to 87.3%, respectively (Figure 15).

Rates of health insurance coverage have grown from 74% to 83% among women and from 73% to 83% among men* from 2014 to 2020, respectively.

*Full coverage rates may be slightly different between sources.

Figure 15: Health insurance coverage in Rwanda

There is some evidence that in Rwanda, CBHI has contributed to a significant decrease in out-of-pocket medical spending and a reduced incidence of catastrophic health care spending.

Exemplars research shows the high and equitable coverage of CBHI has enhanced PHC by:

- Reducing out-of-pocket costs and lowering barriers to access

- Increasing the utilization of health services

- Enhancing community participation in health-related issues

Boosting demand for PHC services such as prenatal care and HIV/AIDS services,,,

Targeted exemptions and subsidies

Rwanda relies on community-based practices to define and track social and economic stratifications nationwide.

Ubudehe

Since 2012, Rwanda has targeted government benefits, including enrollment in premium-free CBHI plans, to the individuals and families who need them most using a village-level system known as Ubudehe. Ubudehe is a community-based practice for categorizing households by socioeconomic category. Community members and leaders sort their neighbors into one of five categories:

- A: Abakire, or well-off households

- B: Abifashije, or self-reliant households

- C: Abakene, or poor households

- D: Extremely poor households

- E: Households with no labor capacity due to age or disability

Since the MoH adopted the Ubudehe system for targeting subsidies, Rwandans pay into the CBHI system on a sliding scale. Wealthier households pay an annual fee for insurance and a co-payment at hospitals and health centers. The poorest quarter of Rwandans do not pay premiums or copayments for the same care. Households in the middle categories (almost three-quarters of members) pay RWF 3,000 per year (US$2.68 as of 2023), and households in the wealthiest categories pay RWF 7,000 per year (US$6.24). This system seeks to boost access to health services for poor and vulnerable households while ensuring that people with means can help support the system for everyone.

As of 2018, Rwandans can dial *909# on their mobile phones to learn their Ubudehe status and pay their CBHI premiums accordingly.

Participating villages come together for up to a week at the beginning of the financial year; local leaders, assisted by community volunteers, collect data measuring local poverty to come to a common understanding of the level of poverty in the community and to set development priorities, determine the best ways to achieve them, and establish ways of funding them. The government provides each community with a bank account and financing, and communities can also do community work in exchange for more government money. The process also operates at the household level, meaning that richer households can support poorer households, for example, by paying for health insurance, buying food and milk for children, farming, and building houses.

Ubudehe classifications are widely used to select beneficiaries of government programs, including CBHI. Other programs that rely on Ubudehe to identify beneficiaries include cash transfers, public works, microcredit initiatives, and a program known as One Cow Per Family in which wealthier households donate cows to their poorer neighbors. Research suggests the Ubudehe program has increased vulnerable communities’ access to food, schooling, and asset development along with health insurance.

Supporting health workers

Figure 16: Evolution of the CHW program in Rwanda

To improve access to PHC, Rwanda also adopted initiatives to increase the number of health care personnel—including community health workers, doctors, nurses, and midwives—nationwide.

Community health workers

Rwanda launched a national community health worker (CHW) program in 1995, in the immediate aftermath of the country’s genocide.,, The program was intended to address shortfalls in access to health care, including an insufficient number of health care workers, and has grown steadily over the years. An initial network of 12,000 MoH-endorsed CHW volunteers quickly grew, and by 2022 there were nearly 60,000 working in villages and peri-urban areas nationwide.,

Two types of volunteer CHWs work in every Rwandan village:

- An animatrice de santé maternelle (ASM, or maternal health facilitator) is a woman elected by her community to make regular visits to pregnant women, both during and after pregnancy, and encourage them to give birth in health facilities rather than at home. ASMs are trained to diagnose and treat malaria, pneumonia, and diarrheal disease, and to promote family planning, antenatal care, and childhood immunizations. They can also refer patients to health centers and hospitals.,,

- Binômes (“pairs”) work in teams of two (one man and one woman). Their duties overlap in some ways with ASMs, but they also focus on the diagnosis and treatment of malnutrition, malaria, tuberculosis, and childhood illnesses; integrated community case management (iCCM); and provide contraceptives. Like ASMs, they can provide referrals to health facilities. The CHW system assigns four CHWs to most villages and peri-urban areas.,,

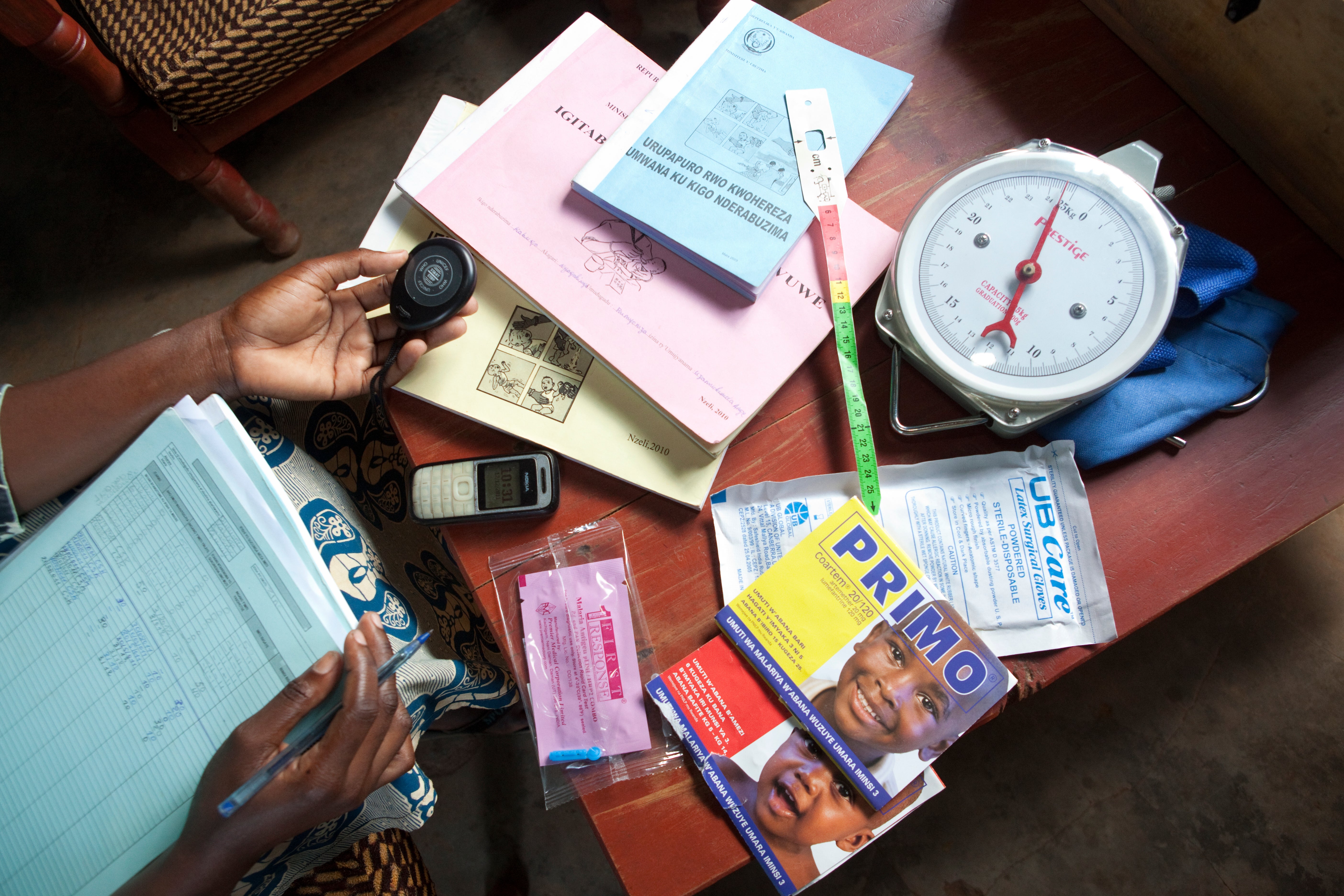

Rwanda’s CHWs are organized through local health centers. They are considered volunteers, though they receive a kit of supplies (including prepaid cell phones), training, and some financial support from income-generating activities. Some are also incentivized for high-quality work via the country’s performance-based financing systems: some incentives are based on the performance of their cooperative as a whole, and others are based on individual performance. (Researchers say CHWs often take home US$5–US$10 per quarter.) They also receive non-financial incentives such as free enrollment in the CBHI program, bicycles, and school fee waivers.

“The CHWs policy brought essential health services closer to the communities. For example, before a child who had fever or diarrhea at night would walk for five kilometers at night with a mother to reach the health center. It was very difficult and that is why the mortality was very high, because such children needed urgent care. So, implementing a community health policy was a very important reform in terms of enhancing primary health care service.”

—Key informant interviewee

Community health oversight

In Rwanda, community health committees reinforce community participation in health and development. They recruit local community health workers (CHWs) and CHW cooperatives.

Rwanda’s community health worker (CHW) program, launched in 1995, improves access to essential health services, especially for mothers and children, providing basic care, maternal health support, and disease management. CHWs are volunteers but receive performance-based incentives through cooperatives. CHW cooperatives are organized groups of CHWs that receive and share funds from the MOH based on the achievement of specific targets established by the MOH. By linking incentives to performance, the MOH hoped to improve quality and utilization of health services.

In each district, a CHW supervisor oversees the collection and analysis of key health indicators, linking these volunteer workers to the formal health system.

Health worker optimization

Figure 17: Trends in medical doctors and nurses in Rwanda

In addition to CHWs, Rwanda has also deployed more nurses, midwives, and general doctors to rural areas, and trained more traditional birth attendants.

For example, in 2012, in partnership with the US government and the Global Fund, Rwanda introduced a seven-year human resource program to build capacity through training in ten priority specialties (internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, surgery, anesthesiology, family and community medicine, oncology, radiology, pathology, and emergency medicine) through long-term partnerships with US universities. Launched in 2012, the Human Resources for Health Program sends nearly 100 US faculty members annually to Rwanda for academic and clinical teaching, aiming to develop the careers of Rwandan clinicians and educators through a collaborative “twinning” model that enhances curriculum, service delivery, and research while fostering long-term global health collaborations. The beneficiaries of this program are the medical, nursing, oral health, and health management students who learn from these professors participating in the exchange. There were also efforts to recruit doctors and nurses internationally, often from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

At the same time, task-shifting increased the capacity of Rwanda’s health workforce. For example, nurses, rather than doctors, can provide HIV testing and basic PHC, allowing doctors to focus on more complex services.,,

Managing noncommunicable diseases

In 2013, Rwanda launched a decentralized, nurse-led outpatient management system for noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). This model integrated diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up in NCD clinics in district hospitals and health centers for illnesses including diabetes, heart failure, severe hypertension, and severe chronic respiratory disease.

Each NCD clinic is led by two NCD-trained nurses, supervised by a generalist physician, and supported by a social worker and a data officer. These clinic nurses also train and mentor nurses at primary care facilities.

The interventions Rwanda implemented to improve the delivery of PHC services close to the community likely increased access to and coverage for those services.

Increasing health infrastructure

Rwanda also improved access to PHC, especially in rural areas, by investing in health infrastructure. These investments increased the number of health facilities – including health larger health centers, and smaller health posts – nationwide and improved their distribution relative to the populations served.

Figure 18: Number of health facilities in Rwanda

In 2014, Rwanda’s MoH initiated a national program to set up new health posts. In 2008, there were only nine health posts, increasing to 505 by 2017, and to 1,160 by 2022. Largely as a result of these efforts, the average time it took to reach the nearest health facility on foot declined from 95.1 minutes in 2006 to 49.9 minutes in 2017.

Figure 19: Share of Outpatient visit by type of facility

To manage health posts, Rwanda introduced the Public Private Community Partnership (PPCP) initiative, based on sharing responsibility between the community, the local leadership, private nurses, and the MoH to set up and run health posts. As of 2021, nearly half of health posts were set up under the PPCP model.

There are two models for health post management in Rwanda. In one, health posts are extensions of local public health centers. In the other, health posts are managed under a PPCP contract. Under these contracts, the health post facilities are owned by the community and local government, who work with a private nurse to facilitate pharmacy and insurance logistics. The PPCP model facilitates the funding and establishment of health posts within communities, especially rural ones, reducing the distance and time individuals must travel to receive care. Furthermore, the contracts foster collaboration between the community, leadership, health care workers, and the MOH to encourage the standardization of care. As of 2021, nearly half of health posts were set up under this PPCP model. The added capacity was especially beneficial during the COVID-19 pandemic, when consultations at health centers and hospitals decreased due to lockdowns and travel limitations, but those at health posts increased by 260% due to their local accessibility.,

Subnational research revealed that the ownership of health facilities varied across districts, with at least 40% of facilities being public in all of them.

Figure 20: Health facilities by ownership

The condition of health facilities in the four study districts is generally very good (Figure 21). For instance, 100% of facilities were found to have functional refrigerators for vaccine storage. The only serious discrepancy was regarding functional water sources; for instance, Gatsibo district reported having such sources in only 35% of its health facilities.

Figure 21: Health facility functionality

Guaranteeing supply and distribution of essential medications

The improved availability of essential health commodities such as drugs and equipment also helped improve access to PHC in Rwanda. In particular, the availability of pharmaceutical products was improved by the establishment of CAMERWA (Rwanda Medical Supply Ltd.), a central procurement and supply chain agency for drugs. CAMERWA ensures supply of essential medications by selling medications to a network of district pharmacies and certain health facilities to generate enough profit to sustain itself.

The establishment of a health supply and medicine quantification management system called the Coordinated Procurement and Distribution System also improved medicine supply chains, and has helped to keep district pharmacies and health facilities stocked. The availability of essential medicines in the country is now closely monitored, with stockout reports provided to the MoH.

Figure 22: Availability and functionality of basic medical equipment at the district level

In a survey of medical equipment availability and functionality in four study districts, the availability of basic supplies such as stethoscopes, scales, and thermometers was found to be generally high.

“We wanted to ensure the availability of quality product in the whole country. I recall, around 1999, the health minister blessed the creation of an independent agency charged with the purchase of all drug products (CAMERWA). Because we are a Ministry, we set policies and regulations but we couldn’t get involved in the procurement and distribution of drugs. So we kept the policy and regulation parts away from purchase and distribution, and that’s how it still is today.”

—KII

The CAMERWA model later evolved to become the Medical Procurement and Production Division. This later transformed even further to the Rwanda Medical Supply Ltd. to regulate and guide price containment of health commodities.

Public Private Community Partnerships

As part of its effort to deliver health services as close to the community as possible, Rwanda also engages the private sector via a model known as Public Private Community Partnerships (PPCPs). They have been instrumental in improving PHC service delivery and access to primary care services, particularly in rural areas. For example, in 2019, Rwanda’s MoH collaborated with a private sector partner to establish eight Second Generation Health Posts in the rural Bugesera district. In addition to PHC services, these health posts offer laboratory services, maternity services, and dental care, and researchers found that they increased primary care use at a comparatively low cost.